Stepping Into the Barbie-verse

Why the Barbie Movie is 2023's Most Anticipated Release

Just a few weeks ago, the internet was lit aflame in response to a clip of Margot Robbie’s foot holding the signature Barbie shape as she stepped out of a jelly heel. The trailer for Greta Gerwig’s highly anticipated movie Barbie (2023) was released, featuring a star-studded cast with the likes of Ryan Gosling, Simu Liu, Issa Rae, and of course Robbie as one of the titular characters. However, the Barbie buzz started long before any trailer for the film was released. In the summer of 2022, photos and clips of Robbie and Gosling in hot pink cowboy fits and rainbow rollerblades surfaced as the cast filmed scenes on California’s Venice Beach. Twitter erupted with excitement, already composing fan edits with the crumbs of footage they were supplied with. It was clear from the behind-the-scenes footage alone that the film intended to be high camp, a suspicion that has been confirmed since the official trailer’s release, which has thrown kerosene on the already blazing Barbie fire.

As someone who grew up playing with Barbies and reveling in the classic, ill-animated Barbie movie franchises, I too am immensely excited for Barbie (2023)’s release (July 21, 2023!). Nonetheless, I can’t deny that Barbie isn’t a character that has crossed my mind in recent years. It’s been well over a decade since I put down my Barbies and packed away my Dreamhouse, and I’m confident I’m not the only young adult alone in that experience. So my question is: why Barbie? And, most importantly, why now?

Starting with the visuals alone, the film’s palette is bright and highly saturated, containing hues of hot pinks and icy blues. The colors and beachside backdrop undeniably scream summer and harken to the vivid colors of the plastic world that many of us grew up loving. In addition to the film’s colors sparking nostalgic joy, they attempt to satiate our culture’s appetite for camp.

Fanatics worldwide are continuing to eat up media like Beyoncé’s RENAISSANCE (2022) and Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) - media that manages to communicate impactful messages while not taking itself too seriously. From the bright hues to the childish dialogue in the trailer (Ryan Gosling’s “Because we’re boyfrien-girlfrien” is burned into my brain), it’s clear that Barbie (2023) is in on the jokes and invites us all to be a part of them. Having clear self-awareness is what enhances media’s camp-ness - it’s what makes it work. This is a quality that more recent tone-deaf pieces (like Don’t Worry Darling (2022)) are lacking, making them appear to pander to audiences melodramatically rather than let them humor at any irony.

In a similar sense, it’s also clear that consumers are generally eager to drink up brighter, more saturated colors. For example, many on Twitter have been quick to call out how dark and dull the cinematography in Disney’s recent reboots have been, particularly in its upcoming The Little Mermaid (2023) and Peter Pan & Wendy (2023) remakes. Many have joked around that Disney needs to “turn on the lights” in these newer releases. Some have theorized that production companies are opting for darker tones to cover up wonky CGI jobs, but others suggest that the colors are meant to evoke seriousness. And they do! While dull tones can, of course, be effective when applied in an appropriate setting, using them in the context of kids films can feel a bit off. The drab palettes convey an often unnecessary solemn tone, one that shouts “Hey! Take this movie seriously because it looks so dismal!” Where did we adopt the idea that media must be sordid to be important?

This brings me to my next reason for Barbie (2023) hysteria: the unequivocal expression of girl joy. I’ve written previously about the power of the sad girl and the rageful girl, but there is truly no emotional expression as powerful as happiness. Joy has long been theorized as not just an outcome of social justice efforts, but a form of activism in and of itself, particularly by feminists like bell hooks and Audre Lorde. Lorde alludes to this in a passage about self-care in A Burst of Light: Essays, writing “caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” Allowing oneself to bask in pleasure in spite of efforts to suppress it is a radical effort.

Barbie, as a character, transports many femme individuals back to childhood, a time that is replete with pure, carefree joy for most. A time when there were no bounds to our imaginations, as our brains were just beginning to grasp the beauty and atrocities of the real world. When nurtured in healthy environments, we were allowed to express ourselves as wildly as we desired, dreaming the biggest dreams we ever would, in some cases. Displaying this unadulterated optimism in the face of life challenges - not for the sake of self-optimization or distraction but simply for the sake of it - is a potent symbol of empowerment.

And it’s clear from early reviews that Barbie (2023) intends to promote similar messages of radical self-acceptance. The current film description on Google is as follows:

After being expelled from Barbieland for being a less than perfect-looking doll, Barbie sets off for the human world to find true happiness.

The IMDb one similarly reads:

To live in Barbie Land is to be a perfect being in a perfect place. Unless you have a full-on existential crisis. Or you're a Ken.

While Barbie undoubtedly has her flaws (namely being a perpetuator of unrealistic beauty standards)1, she was conceived with the intention of empowering the individual girl (and later, of course, the capitalist intention of selling dolls). According to the company, Barbie was invented in 1959 by Ruth Handler who was inspired by her daughter projecting her own dreams and aspirations onto paper dolls. Handler realized that baby dolls only offered young girls the opportunity to imagine themselves as caregivers. Thus, the three-dimensional Barbie doll was born, encouraging girls to imagine themselves as princesses, physicians, presidents, and more.

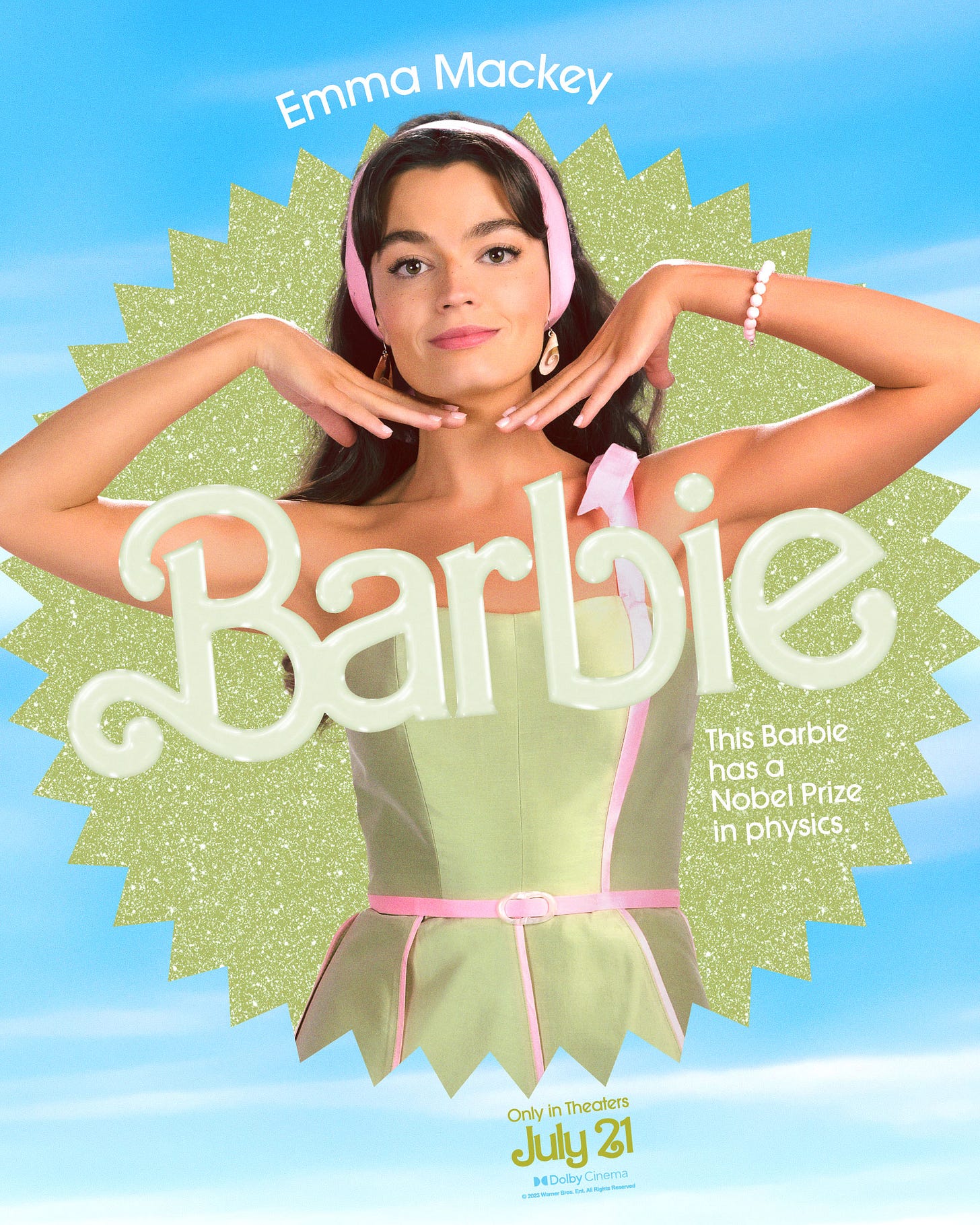

This sentiment - as doctored as it is by the corporation or not (it likely is) - is reflected well in what’s been the most poignant aspect of the Barbie (2023) marketing: the Barbie and Ken posters. While Robbie and Gosling portray the main duo, there are a number of other “Barbies” and “Kens” played by Emma Mackey, Issa Rae, Hari Nef, Simu Liu, Ncuti Gatwa, and others. The Barbie posters explain the professions of each of the dolls, such as “This Barbie is a celebrated author” and “This Barbie has a Nobel Prize in physics.” The Ken posters simply read “He’s just Ken” or “He’s another Ken,” making it clear that it’s Barbie’s world and Kens are just living in it.

The posters help architect a kind of matriarchal society in which power lies in the hands of talented and accomplished young women who are supported by their male counterparts. Barbies revered by Kens. The varying professions and identities represented across the Barbie posters harken back to Handler’s original idea: that a young girl can realize any dream for herself imaginable through her dolls. This message is further cemented for viewers by the Barbie Selfie Generator, in which fans can insert themselves into a Barbie or Ken poster, typing their own caption of what they want to be.

As I alluded to earlier, Barbie dolls haven’t always been representative in terms of race, size, ability, and more. It wasn’t until 1980 that the first Black and Hispanic Barbies were made and 1981 that the first East Asian doll was made, nearly 21 and 22 years after the original Barbie’s release. According to Barbie, for years, “diverse dolls were available but were always friends of Barbie,” not Barbie themselves.

In contrast, Barbie (2023) appears to acknowledge a diversity of dolls across its numerous Barbies and Kens, many of different races with unique identities (even though the main ones are still portrayed by white actors). While the film seems to predominantly focus on Robbie and Gosling’s characters, I am hoping that the lives of the other dolls in Barbieland are explored. The democratization of “Barbie” and “Ken,” in theory, is an important part of Barbie’s messaging, and one I’m glad Gerwig appeared to consider. While often portrayed as a thin blonde, there isn’t just one way Barbie should look or exist, both in terms of physical appearance as well as ambition.

Stories about women’s lives are and always will be in high demand. Mainstream media has offered us a handful of strong women protagonists over the past several decades and I’ve grown up watching many of them get slashed down just as quickly as they’ve been served up, especially those in male-centric genres like action. The trailer for the Captain Marvel sequel, The Marvels (2023), was released recently and met with great disdain from countless bro bloggers, upset about things are trivial as Brie Larson’s (non-smiling) facial expressions. I would hope our culture has gotten somewhat past the 90s-style “you should smile more” misogyny. But I digress. Since its release on April 15, The Marvels (2023) has become the most disliked MCU trailer on YouTube.

In a recent Instagram story on the official Barbie (2023) Instagram, Margot Robbie tells an interviewer she was in awe of the film’s script on her first read, but disappointed because she never thought it would see the light of day. Based on responses to mainstream women-led films like The Marvels (2023), it’s clear to see why that would be the case. If anything, the recent misogynistic responses make an even greater case for why Barbie (2023) needs to exist.

I’m not saying that this movie has emancipatory power. It’s palatable nature may stem, in part, from the fact that it displays women dolled up and in pink rather than fighting intergalactic villains like Captain Marvel, as the public is more comfortable consuming that.

At the same time, seeing the excitement this film has drum up is also indicative of what stories young girls and women are feeling drawn to. What parts of themselves they want to see reflected, what lives they want to live via fiction. These aren’t just the parts that are pink-clad, but the ones that connect them to their inner child, one that was able to realize her ambitions and imagination via toys. Girls and women still deserve characters that they can project their ambitions onto - ones that are unabashedly themselves. They deserve to dream of a world in which they can achieve greatness with unwavering support. To celebrate their wins and rejoice. Those are lofty, ambitious heels for Barbie (2023) to fill. I’ll be tuned in July 21 to see how close she comes to doing it.

As inticed as I am by Barbie (2023)’s expected premise, I am not numb to the ways Barbie - as a character and company - has perpetuated an unrealistic beauty standard for women. Dismantling beauty culture is something I am passionate about and is something I’m eager to see Gerwig address in this film. For critiques on beauty culture, I’d recommend checking out several articles I’ve written previously about desirability, ageism, and the complications of dabbling in beauty culture and protecting oneself from it. I also always recommend

by (I really can't recommend this newsletter enough) for more brilliant critiques on beauty culture, she also recently posted an article on Barbie (2023).Obviously, this article contains my thoughts and speculations on Barbie (2023) based on the trailer alone. Come back in July and I’ll post an update on how I thought the film lived up to the hype (or not)!

The thing I dislike about this movie is that if you stop to think about it it’s a Barbie comercial. It’s longer, will be on the cinema theatres, and has storytelling but I have no doubt that it was only produced to sell more dolls and other merchandise. No surprise it has received so much coverage and promotion.

Most movies now seem to be like that. About products: Mario, Tetris, Air Nike, flaming Cheetos... Hollywood has became even weirder...

I love this! I’m also over the moon about this new Barbie movie lol but I couldn’t quite put my finger on why, but after reading this post I was like “that. That’s it”. Also love your Barbie poster!