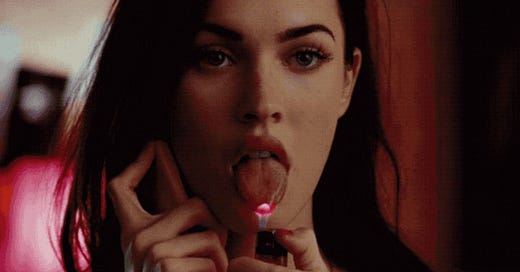

One doesn’t have to go searching too far on the internet to discover girls’ obsessions with onscreen “female rage.”1 On TikTok and Twitter, compilations of “female rage in film” abound, containing countless clips of fictional women murdering people and applying makeup on their tear-stained faces while staring off in a wordless trance. Within these compilations, you’ll most often find clips of Megan Fox’s character Jennifer Check in Jennifer’s Body (2009), a teenage girl-monster hybrid that gains her life force by killing and eating men. Amy Dunne, deranged protagonist of the thriller Gone Girl (2014), often makes the cut, along with Florence Pugh as Dani, the May Queen of Midsommar (2019). Other TV shows and films laden with female rage include Kill Bill (2003), Killing Eve (2018-2022), Fleabag (2016-2019), Promising Young Woman (2020), Pearl (2022), and Mean Girls (2004). Today, new series like Swarm (2023) are cropping up that blend female rage with modern-day stan culture. Popular singer SZA is also making reference to iconic vengeful women in songs off her latest album S.O.S. like “Kill Bill” and “Gone Girl.” It’s clear that the vindictive woman protagonist isn’t going anywhere.

This wave of young female rage-enthusiasts is not anything new, especially not in my lifetime. When I was a middle schooler, female rage was a coveted part of the soft grunge Tumblr aesthetic. A key difference, however, was that the rage was more often than not targeted at oneself rather than others. I and countless other pre-teen girls saw our frustrations and insecurities reflected in artists like Lana Del Rey, Marina and the Diamonds, and Lorde, who crooned about their irritation and distrust in men, adults, and society at large. Lana Del Rey, in particular, had a way of directing her sorrow back onto herself, using self-destruction and submission as fantastical ways to cope with relational hardships. Many middle school girls dove headfirst into this fantasy, in many ways that bordered on unhealthy.

Nonetheless, there can be something quite powerful about seeing your own emotions reflected on a larger stage. A sensation that can make one feel isolated can suddenly become a source of connection across space and time. I think this is part of what has made the female rage trope so universally revered. It’s a kind of wink, a gesture towards a larger population that asks “you too?” Upon which we can all answer “yes, all of us too.”

It’s not that most women have committed homicide or would even want to. It’s that the trope illustrates an alternate universe in which women can seize power by leaning into their emotions - becoming more sensitive in a sense - even if it’s ultimately to their demise. Take Pearl (2022) for example, a film about a farm girl eager to become a movie star, who is stuck at home caring for her ill father and domineering mother. Pearl, portrayed by Mia Goth, was abandoned on the farm by her husband, who falsely promised her a better life but ultimately left her to enlist in the military. Blinded by her rage, an ambitious and brokenhearted Pearl unleashes fury on all she comes in contact with, killing off anyone standing in the way of making her dreams come true. On top of being an intense character study, through its hyperbolized acting and set design, the film excels in symbolizing the turmoil that comes from skewed expectations for young men and women in and out of the home, as well as the dampening of ambitious women in society at large.

In a world in which girls and women have long been expected to suppress “negative” emotions and maintain a pleasant demeanor, a culture that permits the cathartic expression of frustration and anger is understandably appealing. Especially for teenage girls who are just beginning to come to terms with the realities of living within a patriarchy and might just want to scream-cry about it sometimes. In female revenge stories, every wrongdoer, every trespasser, is avenged, restoring justice to not only the singular woman’s life but seemingly to all common women.

Gone Girl (2014), in particular, draws attention to the harsh reality of living in a culture that encourages women to repress emotions in its iconic “Cool Girl” monologue. Gone Girl author Gillian Flynn writes that a “Cool Girl” is a girl who suppresses her feelings to please her male partner, morphing herself into the most attractive girl in his eyes, even if it means becoming soulless in the process. She writes:

“…Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl.”

The protagonist, Amy Dunne, flips this trope on its head by developing a calculated revenge plot to get back at her husband for cheating on her, framing him for her disappearance and revealing his secrets to the public in the process. Amy does anything but suppress her rage. She opens up the floodgates, taking her traitor husband down in her wake.

The common experience of suppressed rage in response to a patriarchal society is what makes the female rage trope work. The image of a woman going on a rampant killing spree to cleanse her broken heart works, in part, because of how fictitious it is. In contrast, the rageful, homicidal man - while done well in satirical work on toxic masculinity like American Psycho (2000) - is too realistic to be a fantasy, particularly in America where male-led public shootings are so frequent that they don’t have time to cover them all in the nightly news.

Of course, when putting these women killers on a pedestal of sorts, a question is bound to crop up: are we glorifying violence? In response to young girl antagonist devotees, I’ve seen many say that they’re missing the point by worshiping them. These critics suggest that the “rageful woman” is merely symbolic. And to transform the anti-heroine into a champion of women is to write off her wrong-doings, ignoring the fact that they are reactions to oppressive systems and don’t exist in some violent fantasy vacuum.

In a similar vein, on the other side of the discourse, many use the rageful woman to further perpetuate egregious stereotypes about women and violence. For example, during the unfolding of the recent Depp v. Heard defamation trial, many drew comparisons between Amber Heard and Amy Dunne of Gone Girl, intending to point out the ways that Heard supposedly faked being an abuse victim in a premeditated attempt to gain clout. Beyond this being an entirely baseless take - seemingly influenced by the physical similarities between Heard and Gone Girl actress Rosamund Pike - it uses a satirical work of fiction to further bolster the hysterical (ex-)girlfriend stereotype. A stereotype that is frequently used to de-legitimize women in a number of spaces, from doctor’s offices to relationships to courtrooms.

What’s more, the female rage trope is not a one-size-fits-all film theme. Many have noted that the scorned woman is most often played by a white woman. This has been a topic of heated discussion on Twitter in the aftermath of Swarm (2023)’s release, a fictional series starring Dre, a young Black woman who goes to violent lengths to defend and protect the singer she idolizes. In an interview with Vulture, show creator Donald Glover says he encouraged lead actress Dominique Fishback to consider her character as “more of an animal and less like a person,” claiming that there was little need for her to find the humanity in Dre. In this fantastic piece in Teen Vogue, contributor Stitch writes that Glover’s lack of care for Dre’s personhood helps stoke misogynoir, or prejudice against Black women. Stitch touches on the issues that occur when complex characters like Dre aren’t written with humanity here:

“Black women aren’t allowed the “luxury” of violence…A world that doesn’t take care of Black women when they’re good sure as hell wouldn’t miss the chance to punish one for committing serial murders across the country. The fantasy falls flat.”

It’s unfortunate that some filmmakers - like Glover - and film consumers alike are co-opting the trope of the rageful woman in a too-tight vacuum - using the sensationalism of a girl gone wild to draw viewers in. In this excerpt, Stitch hits on the crux of what makes the rageful female protagonist possible without the glorification of violence and perpetuation of stereotypes: a touch of human nature and a nod toward its complicated facets. Satire is the use of humor, irony, and exaggeration to expose or ridicule a person or concept. And when applied using these facets, violence in film can be a powerful satirical storytelling device, drawing attention to adverse systems like patriarchy that force people into precarious situations and states of being. When we’re able to understand the context under which the fictional violence is occurring - what led the character to that point - we gain a fuller picture of said character, as well as the systems it seeks to satirize.

I don’t think that characters like Pearl or Amy Dunne are or necessarily should be feminist figureheads for all women to exalt. In most instances (but maybe not all!), there is little to reap from leading with violence, for the antagonist and those being antagonized.

Nonetheless, the rageful woman is a powerful and important emblem and has been throughout history - from Medusa to Jennifer Check. The dramatization of women's emotions onscreen gives women grappling with the actualities of oppressive systems something to potentially identify with. Such portrayals may even grant women the opportunity to be more sensitive to their emotions, aware of the peaks and valleys that come with simply existing. Many female rage stories also excel in interrogating the systems that lead fictional characters and real people to violence - all of which can help us investigate the changes that are necessary to transform institutions for the better.

Perhaps it’s a good thing that hell hath no fury like a woman scorned.

For more on a related topic, I highly recommend checking out this review of Swarm (2023) by the talented

of .I don’t loooove using the term “female” when writing about women, as it’s a word that’s been strangely co-opted by those speaking about women in a derogatory sense. However, the trope is widely referred to as “female rage” online which is why I refer to it as such here.

I enjoyed your article. I think that watching the abusers, cheaters, and the like in these shows is a safe way to disperse the rage we sometimes feel.

I hope that one day, as women continue to rise up and be counted, these types of shows will be tales of old... holding little interest other than a warning not to backslide...

One day. 🙏

I just wrote about this in my newsletter today! I was inspired by Eve Babitz’s Sex and Rage. It really is an interesting trope that I turn to over and over (what does that say about me…)