The trailer for Sam Levinson and Abel “The Weeknd” Tesfaye’s The Idol opens with Troye Sivan asking when our culture last had a “nasty, nasty bad pop girl.” I’m assuming the question is rhetorical - a better one might be when was the last time we had a pop girl that wasn’t painted “nasty, nasty, bad” at some point in her career?

At the time I’m writing this, following its premiere at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, The Idol currently holds a 25% critic rating on Rotten Tomatoes (though initial ratings were in the single digits). The show is premiering months after the publication of a revealing piece in Rolling Stone, in which thirteen anonymous cast and crew members came forward about the show’s violent and misogynistic premise. In addition to co-creator Sam Levinson’s timely, costly, and negligent work habits, the crew describes how the project was transformed from a satire of the shady pop music business to a “torture porn” version of the system it claims to caricature. Director and actress Amy Seimetz initially sought to write a story about a troubled star reclaiming agency amid an exploitative industry. Her work, which was 80% finished, was scrapped and re-shot after she was replaced with Euphoria director Sam Levinson. Reports claim that Tesfaye replaced Seimetz because the project was taking on too much of a “female perspective.” A show starring a young woman, mind you.

The Idol follows Jocelyn, a pop star (portrayed by Lily-Rose Depp) attempting to regain relevance following a public mental breakdown spurred by her mother’s untimely death. She latches onto Tedros (portrayed by Tesfaye), a self-help guru, club promoter, and cult leader who takes Jocelyn under his wing and leads her down an allegedly dark path. Early reviews are saying that the show, in true Levinson fashion, is heavy on the shock value, light on the actual plot and character development. Anyone who’s seen an episode of Euphoria will know what I’m talking about - graphic depictions of drug abuse, sex and nudity, and troubled young (often teenage!) girls and women have become a hallmark of Levinson’s work. Such spectacles are often presented with little sign of reflection on the harmful systems that perpetuate them. They merely exist for the voyeuristic viewer to stare and drool over - clamoring to make sense of characters that likely weren’t written for you to try to make too much sense of. Levinson’s knack for sensationalism over substance is clear in his response to the Rolling Stone piece at Cannes: “I think we’re about to have the biggest show of the summer.”

For years, people - men, in particular - have created work that romanticizes and sexualizes the socially unbecoming facets of the human psyche in women. They have often profited off this work well, in terms of financial and cultural cache. Writer Bethy Squire explains the consistent aesthetic of a woman enduring mental disorder in art, writing that it manifests itself in routine optical attributes, specifically “messy hair, disjointed speech, glassy eyes, [and] inappropriate nudity.” An early example of this beautiful, tragic, “insane” woman is Ophelia in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1599-1601), whose state of madness leads her to drown herself.

Observable, surface-level features have long been associated with psychology (or pseudo-psychology), particularly in conceptions of the psychological states of women. For example, British psychiatrist and photographer Hugh Welch Diamond took photographs of women patients in the Surrey County Asylum, with the intention of studying “the physiognomy of mental illness,” or how one’s face reveals their mental state. The goal was to identify visual signs of mental illness by collecting “objective” photographic records of patients to use in diagnosis and treatment. As you might imagine, this effort has zero grounding in actual science. In addition, as Kimberly Rhodes reveals in Ophelia and Victorian Visual Culture: Representing Body Politics in the Nineteenth Century (2008), Diamond typically posed the patients in his photographs with props meant to exaggerate their madness, including a dead bird and a wreath of laurel and myrtle famously worn by Ophelia herself. He arranged them in a suitable way for viewers of the photograph, readily able to consume their mental disorder through visual indicators. This is not too unlike how mental disarray in women has been extrapolated through visual means in contemporary media.

Squire refers to Terrence Rafferty’s review of The Dangerous Method (2011) starring Kiera Knightley, in which Rafferty claims that film “tends to concern itself with the inner thoughts of a beautiful woman only if she's insane, and to only care about the insane if they are beautiful women.” Think Natalie Portman in Black Swan (2010), Angelina Jolie in Girl, Interrupted (1999), and countless others. Our culture is willing to entertain mental illnesses in women that are beautiful. But even then, entertaining them often consists of just that: viewing them as visual spectacles for our consumption, with little to no critical thought on how isolated and societal conditions contributed to a woman’s so-called “unraveling.” We marvel at her madness - messy hair and glazed eyes gleaming. Her state of disorder may even make her all the more beautiful - how brave is she to bear her derangement for us to see? Raw, vulnerable, even pornographic - and not always on her terms.

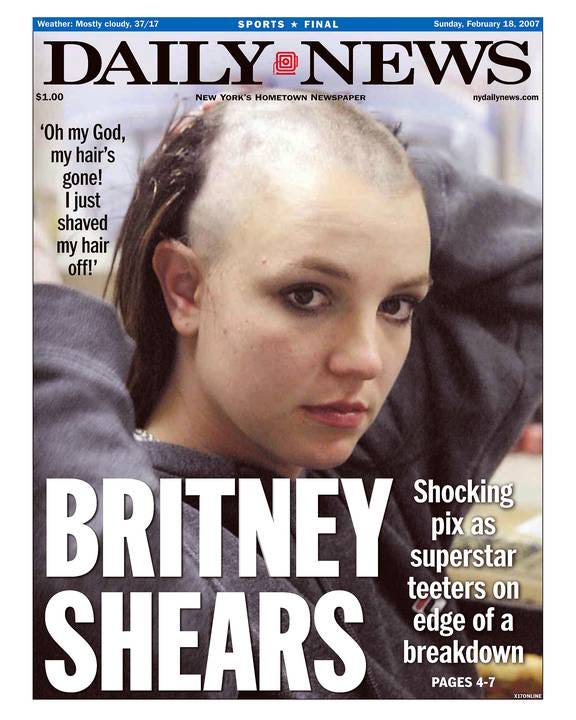

The textbook case for our culture’s fascination with mad women in the “real world” is the mainstream media’s treatment of Britney Spears. In 2007, Spears endured a plethora of personal low points - she was checked in and out of drug rehabilitation centers, underwent a messy, public divorce, was forced to hand over custody of her children via court order, and was placed under a conservatorship - controlled by her father - which she only just recently broke free from. In classic early 2000s tabloid fashion, the majority of public discourse about Spears’ state of being revolved around the visual aspects of her breakdown.

The public’s obsession with Spears’ spiral manifested in an obsession with her shaved head - a physical representation of her neurosis. Rather than discussing how her behavior speaks to our culture’s harmful obsession with celebrity and the effects of exploiting young talent, publications gawked at Spears’ scalp. “Shocking pix as superstar teeters on edge of a breakdown” read the headline of the February 2007 edition of Daily News, along with a photo of a distraught Spears, head freshly buzzed after checking out of rehab. A 2007 Us Weekly cover featured the same photo, along with the words Help Me.

Spears’ personal hardships thoroughly lined the pockets of major media publishers, giving magazines little incentive to quit throwing salt in her wounds. “When you found a celebrity - I hate to say it - spiraling or acting abnormally, that was the story. And we knew it would sell magazines,” former Us Weekly editor Jen Peros told The New York Times in 2021. Peros confessed that, at the time, the Britney story was making the magazine so much money that they sent a reporter down to Antigua where Spears underwent rehab.

Shedding herself of her blonde locks - stereotypical symbols of the youthful, feminine beauty she hooked fans with - shattered the public’s reality. Spears possessed a good-girl-gone-bad air, but now that a seemingly “sane” girl had gone “insane” - and in a highly visible manner - people were floored. Unsurprisingly, her album Blackout (2007) debuted at #2 on the Billboard charts that year. People love an insane girl that’s beautiful, and when beautiful girls are insane.

Britney Spears isn’t the only woman celebrity whose personal debacles have been made into salacious spectacles, ripe and ready to be devoured by the public via media platforms. Miley Cyrus and slut-shaming, Lindsay Lohan and substance abuse, and most recently, Amber Heard and domestic abuse. Time and time again, women are nailed to their respective personal trials - made out to be crazy, conniving, evil, and beautiful - almost always beautiful. We only care because they’re beautiful. Lindsay Lohan’s mug shots are still circulated on Twitter with fervor - eyes glassy, hair messy, and eyelashes perfect. Women have been cast repeatedly as the stunning lead stars in aesthetically pleasing one-woman tragedies, having their dirty laundry aired out and made dirtier by those who stay rich off its filth.

And now, thanks to The Idol, we will soon experience a resurrection of the mad, bad girl aesthetic. From the sexualized pop star persona, to the blonde hair, to the public breakdown, to literally playing “Gimme More” in the show’s trailer, it’s clear that The Idol’s protagonist draws inspiration from Britney Spears. And if Levinson is true to his signature style, the show will approach the topic of young women's exploitation in pop music with a lens that lacks critique and makes madness into a conventionally attractive, sexualized spectacle. In many ways, Levinson isn’t so different than Hugh Welch Diamond, placing a wreath of laurel and myrtle on his Ophelias in the form of excessive onscreen nudity, devoid self-esteem, and little hope for growth.

There is virtually nothing artistic and subversive about deriving pleasure from a woman’s suffering. It’s not brand-new or unique, it’s dangerous and sadistic. Levinson is causing harm by aestheticizing that suffering, associating sexual freedom with neurosis, and making violence look sexy. I won’t be tuning into The Idol (I’m sparing Levinson my streams), but I’m sure I’ll be able to feel the reverberation of the mad, bad girl resurrection far outside its wake. I hope I’m somehow wrong.

For more on Sam Levinson’s perverse history as a creator and nepo baby, please check out this great article by

. For more on Euphoria and the harms of hyper-sexualizing girls in media, check out my piece “The Gender Modesty Gap.”I also recently wrote this piece on women's rage in media, which features some movies that I think depict women's anger and madness in a more holistic, contextual, and subversive light.

Wow, I love this so so much! My jaw literally dropped when I read that they they felt the show had “too much” of a female perspective when it literally has a female lead... it’s so sad that women’s stories (that are actually from their perspective) continue to be put aside in favor of capitalizing off them and their suffering.

Truly appreciate your commentary on this! Everything you explained is exactly why I’ve been unable to bring myself to watch Euphoria no matter how much I’m told to watch it. Thanks for sharing!

The ripple effect I fear the most is the further glamorization of mental illness in young girls as an aesthetic (i.e. “in my fleabag era”) instead of extending compassion to the people this show is clearly taking inspiration from and re-examining the damage that’s been made.