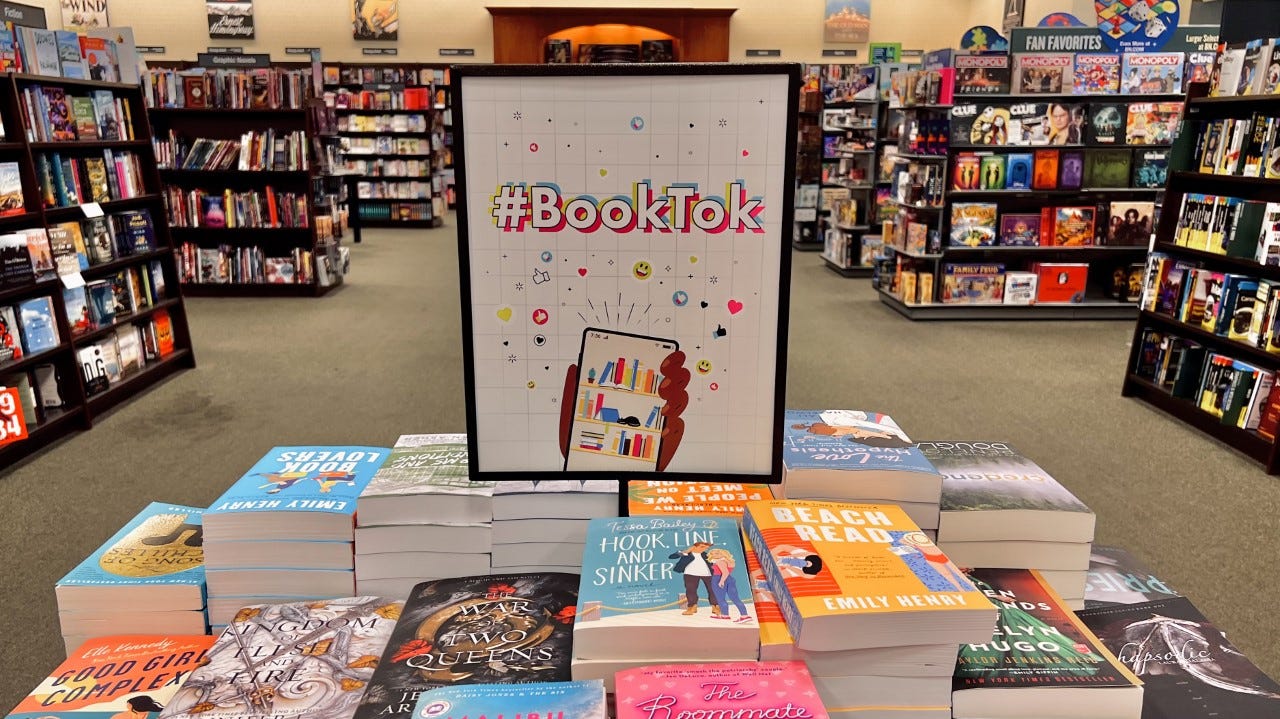

Suppose you've been to a bookstore recently. In that case, you've likely seen a table near the front of the shop clad with paperbacks that all sort of look the same. They are clad in bright primary and pastel colors and their titles are scribed in a kind of handwritten, beachy italicized font or bold block letters. The cover features striking illustrations of an animated couple. The couple is typically white and they’re typically embracing, smooching, or scowling at one another. Most books on this table are written by Christina Lauren, Emily Henry, Ali Hazelwood, Colleen Hoover, or another popular woman author whose name you may have scrolled past on your For You Page. On the display, you will likely see a sign that says #BookTok along with that multicolored musical note logo that’s hard to mistake.

BookTok is a now not-so-niche strain of content on TikTok related to all things books. Under the hashtag, you will find mainly young women gushing about their latest read - typically a book in the YA romance or fantasy genre. You will also find montage videos of pretty Pinterest images set to music, intended to capture the “aesthetic” of a popular novel. You will find book hauls, recommendation videos, generally vibey clips of TikTok users reading and marking up their books with dozens of multicolored sticky tabs, and much more.

I paused reading for pleasure in college, largely because my coursework required mulling over dense academic texts for hours on end. For leisure time, I much preferred unplugging my brain in front of my tiny and small screens, scrolling away on my phone, or watching a TV show. When I graduated and suddenly had time freed up, I was eager to get back into reading and looked to TikTok, as one does, for inspiration on what to dive into. The summer I moved to New York, I packed copies of The Soulmate Equation by Christina Lauren and Beach Read and Book Lovers by Emily Henry. These books provided me with the ultimate comfort as I adjusted to my new home. They were quick, easy, and by and large predictable - bestowing me the bliss of a 2000s rom-com marathon or Gilmore Girls binge.

After some time, however, I began to crave books of a different variety - perhaps stuff a little headier, a bit more unexpected and deep, and written in more unusual tones. I had grown a bit bored of the BookTok genre. As I leaned into more traditionally “intellectual” works, I grew a bit of an aversion to the popular category of novels. When I picked up random books that I enjoyed - like Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow (2022), one of my favorite reads of this year - and later learned they had blown up on TikTok, I became quickly embarrassed. Like when you hear a favorite, formerly indie song play on the radio.

Call it my individualist urge to revere and gatekeep niche media to feel “special” and perhaps a dose of internalized misogyny, but I felt utterly done with the culture of BookTok. Apart from the YA romance genre no longer being for me, there seemed to be some other factors deterring me at an ample pace

For one, the focus of BookTok seemed to shift away from the reading itself and more toward the identity of being a reader. You would think that the act of reading precedes the label of “reader,” but social media famously facilitates the development of appearance without substance. People can appear as readers by adorning themselves with a myriad of markers, none of which are actually “reading the book,” as that’s impossible to fully encapsulate in a sixty-second video. Instead, the focus shifts to the aesthetics, which include the vibey Pinterest videos (many of which I actually enjoy) and the purchase and consumption of many, many books, all of which are tagged with copious sticky tabs to ensure viewers that you are in fact reading the book.

In a realm where all one can do is “show,” consumption acts as a kind of cultural currency - owning lots of clothes shows the world you’re a fashionista, owning lots of books shows people you’re a voracious reader. In this opinion piece for The Guardian, writer Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett writes that “some people treat books like magical totemic objects.” In this vein, people treat “having a lot of books as a stand-in for [their] personality.” The phrasing of “having” a lot of books instead of “reading” them is key. I can’t tell you how many memes I’ve come across in the last year about buying books before you finish the ones you own (I’m also personally guilty of this). Being able to goofily laugh at the mammoth number of books you read or purchased that year online and to friends (“I have a problem!”) contributes to your bookish, cerebral identity. As does filming and uploading yourself sobbing at a book’s conclusion - another trend that’s made its rounds in the BookTok vertical.

The obsession with consumption is part of what’s most troubling about BookTok to me. Social media has a way of ramping up consumerism - leveraging the influence of popular users to push fast fashion, furniture, cooking supplies, and just about any other type of consumer good. More, more, more. This consumption obsession translates to the BookTok space, in which hefty book hauls and yearly reading goals dominate peoples’ feeds. It seems, at times, that the desire to own or read a large number of books can detract from getting mindfully lost in the story, gliding through at your own pace.

The subject matter of popular BookTok books is also of note, as it mirrors the type of content that succeeds on social media itself: digestible and sensational. Similar to the palatable short-form content that succeeds on apps like TikTok, BookTok books of the YA variety often contain predictable storylines that are easy for readers to swallow. We can begin the book confidently, knowing that the enemies will turn into lovers and that the fake dating will turn into real dating - all will be tied up with a neat bow. Yet, these books are as chewable as they are laden with spectacle: they often contain a lot of vibrant “smut,” or graphic sexual material. There are entire TikToks dedicated to recommending books that are the smuttiest. This type of material can advance or accompany the plotline but can feel out of place in otherwise lighter YA stories. In some of the BookTok books that I’ve read, I’ve noticed that the smut is, at times, clumsily injected into the storyline, as if inserted at the last minute to meet some kind of erotica quota.

As with some of the hyper-sexual material, other aspects of BookTok books can have a manufactured quality. That’s likely because they are being produced by a publisher that understands what sells, on a granular, algorithmic level. It’s not uncommon for publishing houses to reach out to BookTok influencers to promote their newest releases - books that have been meticulously selected and written with a conscious and unconscious awareness of what will thrive online.

Since its birth, social media has morphed into a near-perfect version of word-of-mouth marketing. This characteristic has been beautiful to witness in its organic state - when people make and exchange art and ideas online, connecting with individuals and materials they otherwise wouldn’t be able to access offline. However, in its darker state, the power of influence online has been leveraged by corporations that prioritize selling over connecting, and in doing so, transform works of art into dampened commodities.

In her essay “The Algorithm Killed the Radio Star,” writer and musician

discusses how emerging artists experience pressure to release music that will thrive on TikTok’s algorithm, which often means producing songs that feel gimmicky. Short, hook-y, and easily sharable and digestible. Such pressure can lead to a degradation in artistic integrity. “When the key to success is to hack an algorithm, artists are incentivized to become hacks themselves,” McLamb writes. Nowadays, I fear publishing houses are commodifying books in the same manner that record labels are commodifying songs: by creating work that appeases a sterile algorithm to move the most amount of units possible.Whether or not one enjoys BookTok books is less of the problem - I’m not in the business of dictating personal tastes. I, myself, have enjoyed certain books that have gone viral on TikTok and appreciate all kinds of mainstream media (I’m a serial Taylor Jenkins Reid reader and a Swiftie for crying out loud). I’m a fan of young adult fiction and am generally skeptical of anyone disparaging media solely because it’s loved by young girls and women. And I have BookTok to thank for getting me back into reading post-college.

Nonetheless, I think that BookTok acts as a helpful case study, showcasing how companies will find any way to capitalize on what people love online. Our current stage of capitalism thrives off bottling peoples’ passions and interests and selling them back to them in a cheapened, sterilized package. This inevitably leads to the erosion of artistic authenticity and books becoming less of an art and more like products that tick the right boxes. In such a landscape, I think we are all better off reading books and being discerning about the art we immerse ourselves in. Reading is even more fun, somehow, than being a reader.

An article of mine that accompanies this one well is “Is Commercial Art a Paradox?” which similarly discusses the dampening of art for profit in the digital age. I also reference McLamb’s article in that essay because it’s simply that good.

i feel like everyone who really really loves booktok erotica and actively seeks out books with smut is just someone who wouldve thrived in fanfic communities but just landed on booktok first, because fanfic is honestly what theyre looking for. stories with predictable plot beats and relationships, which are more about fantasising about specific events rather than telling a story with themes, motifs, ~intellectual~ messages, etc--you’ll find that stuff in fanfic way easier and honestly its probably better than whatever book a publishing house got an influencer to promote for you. this isnt really related to the article but its something ive been thinking about a lot, especially now that fan internet communities are so segmented now bc of algorithms

I read an article recently about how booktok has turned book production / publishing into fast fashion - books are being published with incredibly fast turnover and are lacking in many areas. The hype is pushing the purchasing of the book rather than the quality of the book - there’s huge quantity over quality issues.

I think it’s nice booktok has introduced many people to reading or to get back into reading, but I do also think booktok has slightly ruined the publishing industry.

On another note booktok is incredibly damaging in other ways - the books they push are so insanely white washed, heterosexual and western / English speaking books. It has many flaws. There’s always power for it to change though - and maybe it will! Because a lot of the books circulating now are so oversaturated I see a lot of people complaining about the lack of variety that booktok pushes.