When asked who my favorite musical artist is, I often reply with “Taylor Swift,” as she is undeniably the singer I listen to most and whose songs I connect with the deepest. But to say that one likes “Taylor Swift,” as a singer/songwriter feels inadequate, given how herculean her empire has grown. Make no mistakes, I write this as a steadfast Swiftie, but to love Taylor Swift is to love something bigger than an individual artist. It’s to love an entity - a business, a brand. When you buy into the Swift-verse via streams, concert tickets, and merch, you’re not just buying into the songs. You’re also buying into the castles and ball gowns, sequins and rainbows, snakes and swords. Taylor Swift and her eras are akin to Disneyland - outfitted with Reputation Land, Lover Lane, and Folklore Square. It’s the reason why fans and their parents are willing to dish out thousands of dollars for tickets to The Eras Tour - the experience is akin to attending an all-inclusive resort with theme park access.

Given the commercial success that artists like Swift have achieved, it can be challenging to even think of them as real human people, let alone as artists. “Artists,” as they’ve been historically conceived, are outcasts - those who bare their souls and often face societal rejection for expressing unconventional ideas through unorthodox means. Many would argue that Swift has bared her soul time and time again and has even faced societal rejection, laden with internalized and overt misogyny. And at the same time, The Eras Tour is projected to double her net worth, tipping her over to billionaire status - a phenomenon that feels rather inhuman. Millions of people are willing to pay a month or two of rent money to collectively bare their souls alongside her. A similar phenomenon occurs in the Marvel and Pixar universes. I can’t count how many times I’ve shed tears to media that feels uncharacteristically human that was also distributed by billion-dollar corporations.

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), Irish novelist and critic James Joyce distinguishes “improper” and “proper” art. “Improper art” contains what Joyce calls a “kinetic” quality, in that it strives to move people in a certain way. It compels them to act, to experience feelings of desire, fear, or loathing. He explains how improper art is epitomized, in part, through advertisements - work that urges people to act, to purchase. For this reason, Joyce finds this type of art to be “pornographic” in nature - it indulges viewers, inciting visceral feelings and moving them to engage in some kind of act external to the art itself.

By contrast, “proper art” intends to evoke awe and amazement in viewers, sparking an internal experience akin to spirituality. When viewing proper art, viewers momentarily experience an altered state of mind, free from personal concerns in the material world. It doesn’t ask anything of viewers other than to experience that very sensation, it’s what other art critics refer to as “art for art’s sake.” Professor Joseph Campbell sums up the theory well in this quote:

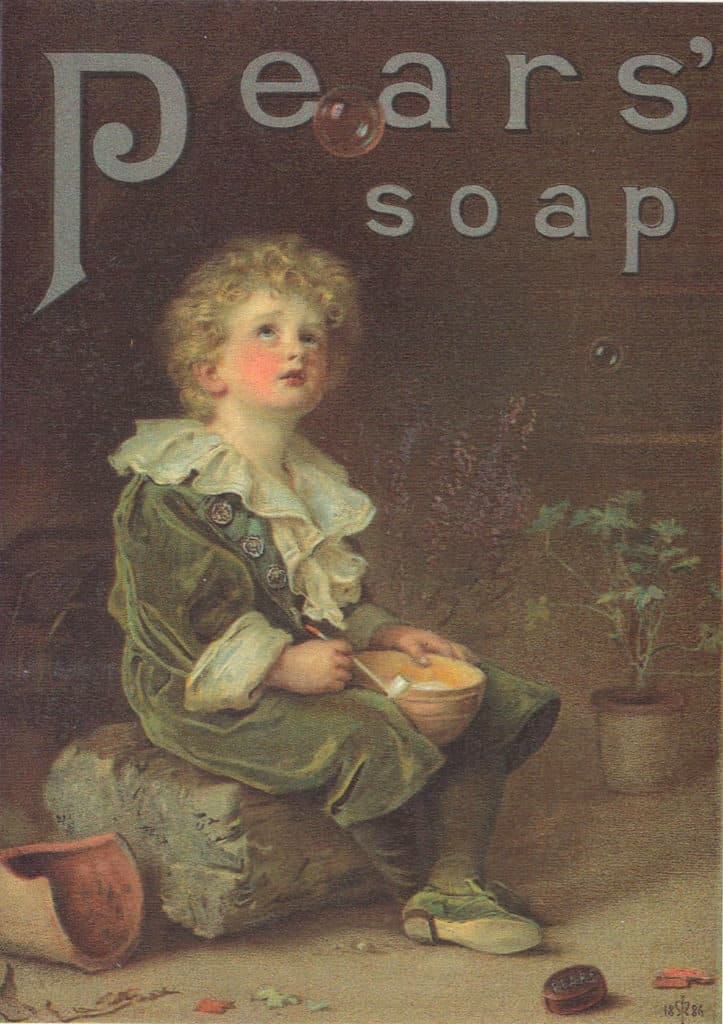

In this article for Artland Magazine, Pablo Anton traces industrialization and globalization with the creation and co-opting of so-called “fine art” for commercial means. He explains how the painting Bubbles (1886) by Sir John Everett Millais was adopted by the British soap company Pears to serve as a print advertisement. It’s fascinating that out of the context of an ad, the painting induces poignant feelings, drawing us into an opportune moment of wonder (and perhaps fear) arrested by the artist. However, with the brand name slapped onto the image and with its placement on the side of a building or in a magazine, those same feelings are evoked in the service of selling. Our relationship to and conception of proper vs. improper art is rendered conditional and contextual.

Anton credits the Art Nouveau movement of the late nineteenth century as a merger of art and commercial exploitation, which is fitting given the context of the Industrial Revolution. During this time, the production of goods had shifted from hands to machines as more efficient manufacturing processes were sought out for an ever-hungry consumer class. Anton credits Czech painter Alphonse Mucha as exemplifying this transition through his signature artistic style: crisp lines, graphic colors, featuring chic models, and being easily reproducible (like the chorus of a good pop song). We can observe this style further calcify in the Art Deco movement of the 1920s, a time romanticizing excess, glamor, and cosmopolitan living. Commercial art from this era idealizes consumption, aiding a capitalist society in which producing and selling are the sole objectives. Attributes of this ad style are further witnessed during the post-war consumption boom of the mid-century.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, commercial art bolstered capitalist ideas - the same ideas that provided the backdrop upon which the art was created. The values and the work itself functioned in concert with one another, one couldn’t necessarily exist without the other. Brave New World writer Aldous Huxley built upon this idea, claiming that those who appreciate commercial art “may be expected to like the product with which it is associated.” Huxley also reasoned that commercial artists can’t necessarily create masterpieces, as their art seeks to “captivate the majority.” The jury is out on whether Huxley would be a Swiftie.

All artists seek to create art that is authentic to them, expressing the messages they strive to communicate and boldly experimenting to forge a distinct style. They often strive to distribute their art to others and with the right combination of talent, strategy, and luck, they cement themselves as legends in the cultural zeitgeist as Taylor Swift has done.

And, artists are also humans surviving in the same society as the rest of us - one in which money is necessary to pay for food, shelter, and all other goods and services. If one is to make money off their art in such a society, there is, unfortunately, a balance to be struck between creating work that is genuine to their artistic spirit and work that can reap material returns. Oftentimes when one is creating to cater to the masses, there is only so eccentric their art can be.

How does one reconcile this? How can one strike such a balance between artistic authenticity and commercial palatability? The short of it is that it’s extremely challenging, as the two approaches are often always at odds with one another. For example, in this brilliant article, Eliza McLamb discusses how new artists must “hack” TikTok algorithms to allow their songs to gain traction. Such “hacking” typically involves producing a song with an indubitably catchy hook, that is short enough for TikTok users to consume and decide they enjoy before their attention is pulled to the next thirty-second clip in their feed (note the parallels to Mucha’s art style). McLamb interviews artist Ash Tuesday on the phenomenon, who replies with:

“It takes the art out of it, it really does. It makes it so cookie-cutter, so pop, but pop in its worst form. Where it’s not even creative, everything is sounding the same. But some people really do enjoy that and that’s great, I love that for them.”

It’s not to say that people who enjoy pop music are somehow artistically stunted or not enjoying the “right” kind of music. I personally enjoy pop music and revel in how it has formed communities through fandom efforts. I also don’t mean to suggest that all artists that have found commercial success are creatively corrupt - only creating art that will pander to the people (though, that certainly may be true in some cases). It’s just to say that we, as a culture, may float towards a kind of artistic bankruptcy if we only appreciate art that is readily sanitized and made easily digestible, often with some kind of symbolic or material buy-in that suspends you from just listening. What would it mean to be an enjoyer of music by popular artists like Taylor Swift or Harry Styles without making the financial and time-dense investments required of a “Swiftie” or a “Harry”? And what other kinds of art could we avoid siloing off without such investments?

Small artists deserve the ability to survive capitalism while also making art that speaks from their souls. As someone who has tip-toed in the world of professional dancing and writing, I’ve witnessed first-hand the kinds of artistic sacrifices that many working artists feel they have to make to do what they love for a living. This includes taking work that doesn’t provide them with meaningful compensation or protection, so long as it puts them in proximity to art-making. This includes putting soul-feeding art to the wayside and picking up more commercialized work that will garner the returns necessary to live life.

For example, the magnetic allure of capitalizing on the internet’s “discourse of the day” as a writer is ever-present. Sneezing out newsletters on so-called “topical” subjects - ones that the algorithm will favor - is enticing. Sometimes my area of interest does indeed waver towards the mainstream, other times I feel uninterested in what the masses are discussing. At times, it’s hard to tell whether I would benefit from writing about a subject because it would creatively fulfill me or simply because it’s buzzy. It can be challenging to discern what I’m interested in and what I should be interested in for my work to gain some kind of commercial stamp of approval from the people that should like it.

But to reiterate what Huxley once said about commercial art: “there are no masterpieces.” While perhaps a blanket statement, there are a few things to take away. The first of which is that creating work that maintains an adverse status quo is not necessarily the hallmark of an ingenious artistic intervention. At the same time, it’s understandable why smaller creators feel they must cater to the masses because we are people surviving a system in which profit is almost always put above appreciating art and human connection. Until artists start receiving the support necessary to thrive off their art-making (improved and comprehensive public and private funding for the arts being a part of it), this paradox will exist.

As a person operating in a creative field, I feel no greater sense of satisfaction than when I take an idea from infancy in my brain and develop it into a fully formed creation that others can observe, interpret, and respond to. Oftentimes, the idea doesn’t even begin as something capable of communicating with words - it’s just a feeling, an inkling, the slight firing of neurons. And when I experience that hit of joy when I’m able to nail down what I have to say and the way I want to say it, and that second hit of joy when others feel seen in my work, nothing else comes close. It’s an experience that’s deeply internal and mirrored when I consume work by other artists that I imagine feel that same rush when creating. It’s a feeling that doesn’t demand or attempt to seduce. It just is.

Appreciate this one, Madison! Striking the balance between "commercial palatability" and eccentricity seems like the key to unlocking the 'greatest' success, but then I have to wonder what that word even means... etc., etc., etc., ...... ..

You always perfectly articulate things I've been thinking and feeling. And this is something I've been thinking about a lot lately. Love this and your writing!