Aristotle’s Poetics (335 BCE) is one of the earliest surviving works on dramatic theory. In the piece, Aristotle differentiates “tragedy” from “comedy,” explaining that tragedies are concerned with serious, important, and virtuous people and comedies focus on weaker, less virtuous characters, those one can poke fun at. He writes that tragedies possess six essential elements: plot, character, diction, thought, song, and spectacle. Spectacle refers to the visual components of a play, including sets, costumes, and props. Aristotle mentions spectacle last in his list of a tragedy’s parts, likely because he believes it to be the least artistic aspect. He writes that spectacle is “connected least with the art of poetry” and “depends more on the art of stage machinist than on that of the poet.” Since tragedies can be read and not performed, spectacle isn’t completely necessary for one to consume a dramatic work.

But if there’s anything we’ve learned from the twenty-first century and its sensations and scandals it’s this: spectacle can sure enhance tragedy.

“Spectacle” was certainly on my mind as I frantically refreshed Twitter every hour a few weeks ago, eagerly seeking updates on the missing OceanGate submersible. The public had been informed that the sub, called “Titan,” contained approximately 96 hours worth of oxygen for its five billionaire passengers, who had each paid a quarter of a million dollars, respectively, to see the Titanic remains in the deep ocean. A broadcast news program displayed a banner along the bottom of viewers’ screens, counting down the hours of remaining oxygen in the submarine like the New Year’s Eve ball drop. Twitter erupted with commentary, making jokes about the passengers playing “Never Have I Ever” as the sub remained stuck on the ocean floor. Others theorized about fights breaking out, crying, and hysteria as the passengers huddled together to keep warm, awaiting a rescue that may never come. By the sounds of the drama unfolding in the discourse, it seemed as though we were going to have an Emmy-award-winning Max limited series on our hands.

In reality, there were likely few tears or shivers or wails 12,000 feet underwater. Rather, the sub - which was hastily built with unsound materials and controlled using a Bluetooth Logitech controller - imploded. OceanGate founder Stockton Rush admitted he had “broken rules” to build the submersible in the name of innovation. Rush died along with the other four passengers aboard the sub.

Upon hearing news of the sub’s implosion, internet users glanced around the room at one another awkwardly, stifling embarrassed chuckles. And then their attention quickly deviated elsewhere. “Oh yes, of course, it imploded,” we seemed to say silently and collectively, moving on from the drama we had crafted around these five souls and their imminent rescue or demise.

In reality - and of course, it’s easy to say this in hindsight - implosion was the most likely outcome for a vessel constructed of ill-advised, recycled materials with 6,000 pounds pressing on its exterior. Perhaps if we had really sat and had a good think about it - had been exposed to all the evidence - we would have thought this to be the case. Publishers certainly could have incorporated these material realities when reporting on the situation. But of course, no one did any of that. There’s nothing romantic about an implosion.

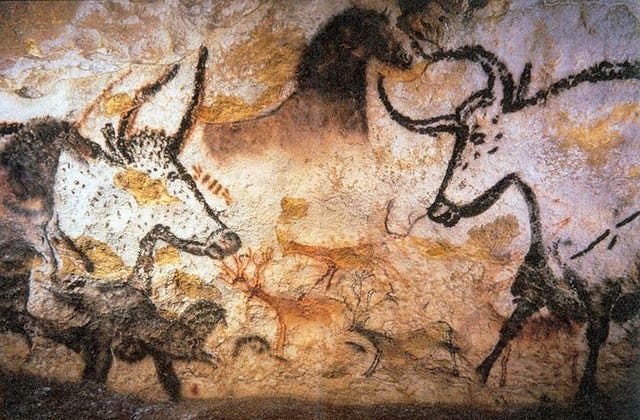

It’s been theorized that storytelling developed not long after human language developed itself. According to National Geographic, some of the earliest evidence of stories comes from cave drawings in Lascaux and Chavaux, France, dating back to about 30,000 years ago. The drawings - many of which depict animals, humans, and various objects - are thought to represent visual stories, some of which were likely accompanied by oral stories. The oral tradition is how many stories survived: the Greek The Iliad and the Sumerian The Tale of Gilgamesh were passed by word of mouth, as well as various spiritual and creation stories among Native American tribes like the Choctaw and Cherokee. Egyptian hieroglyphs - writing in the form of pictorial characters - were used to transmit tales as well. Technological innovations like the printing press and mass media would much later make the spread of stories all the more expedient.

Lessons can be taught and information can be relayed through unfussy spoken word. We can simply tell our children our thoughts on how the universe was created or why they should look both ways before they cross the street. But the perseverance of storytelling suggests the human race’s flair for the dramatic. We want to give and receive important information and lessons to survive - and we also want to be entertained. Sure, we subliminally know that it’s not desirable to be cocky or overly impulsive - but we better know that “slow and steady wins the race” thanks to The Tortoise and the Hare. We know not to walk by certain houses in our neighborhood because local legends teach us which residences are haunted. Communicating life teachings through stories not only makes them easier to recall - it makes us feel closer to those around us and makes life all the more interesting to live.

Stories, like so many crafts and acts that once retained significant cultural esteem, have been reduced to goods and services - and commodities - in many twenty-first-century domains. As Jia Tolentino writes in her essay “Always Be Optimizing” (2017), meals a la Sweetgreen consist of uniformly chopped salads and grain bowls, designed to fuel the worker as expediently as possible, allowing them to eat their meal with one hand and scroll on their phone with the other. $200 treadmill pads turn necessary bodily movement into a flexible asset, permitting people to type at their standing desks while simultaneously hitting a step count devised by a wearable wrist tracker. Meditation is conducted in five-minute bursts, intended to clear one’s head so they can continue working.

These highly optimized endeavors are commodified in the service of a larger economic system that relies on people purchasing nearly as often as they work. Everything is enabling the sale of something else or the endurance of a laborer whose work is necessary for that sale in some capacity. In such a world, stories, too, become commodities.

If you search “storytelling” on Google, you don’t have to scroll too far to come across TED Talks and Forbes articles about how storytelling is “disrupting” traditional marketing tactics. If you put “brand” in front of your “storytelling” search, you’ll come across numerous books and courses on how to communicate your personal and organizational story to the public, most likely for the purpose of - you guessed it - selling.

But, of course, it is necessary for organizations to communicate with the public. And many want to be informed about the premises of the companies they’re transacting with. However, if there is no “story” behind one’s organization other than the tale of a desire to make hordes of cash, a story must be retroactively written. When a facade is constructed to conceal an organization’s unromantic motives, it often reads as hollow or is otherwise packaged in a way that’s easily digestible and shareable. In such a world, stories are reduced to “About Us” pages with recycled jargon. Daily Mail Snapchat stories. Tabloids. Listicles to drive clicks. Reboots and remakes of stories we know sell. The way one teaches and entertains others is scrutinized, iterated, and refined (usually through simplification) until it’s the perfect bite-sized vignette. Humans, in turn, are able to gobble up hundreds of “stories” a day.

The OceanGate Titan story was just one of those hundreds of stories a couple of weeks ago, but one that got drawn out past its typical five-minute slot. In mainstream news, it was painted as a tragedy - a serious situation with serious characters, all of whom were potentially suffering a painful death while loved ones prayed for their safety. The internet - in most spaces I saw - colored the ordeal a comedy, in which billionaires paid a quarter of a million dollars to seal themselves in a coffin, including the sub’s creator who - like the Titanic’s - demised alongside his faulty vessel. The story - whether steeped in sorrow or irony - was spectacular, in that the public adorned it with elements of a spectacle, allowing it to endure for a couple of days (which is nearly a decade in the contemporary news cycle).

Perhaps we were craving the kind of paramount epic that most only associate with an “older” world. A reason to put down our compostable forks, shoveling our thoroughly diced vegetables, and ask our coworkers “Did you hear about the submarine thing?” Engage in the unfolding of a saga that takes more than a few minutes to consume, outfitted with spectacular bells and whistles. But in the end, the submersible story was as short-lived as the vessel’s voyage. Attention came and went, and then the discourse wheel was spun again.

If humans need narratives to survive, the commodification of storytelling will surely contribute to our dissolution. Whether it’s endorsing the proliferation of misinformation, the collapse of commercials and content, the hyperspeed optimization of news, or the general shrinking of attention spans, it’s tough to say that we live in a golden age for spinning yarns.

When every story is squeezed into an abbreviated niche - centering on the same old (privileged) characters - there is little to do with the tale other than discuss using our familiar scripts and then move on to the next. Being permitted the ability to sit with something for a little longer than a few minutes with the motive of understanding and deciding how to feel and act could benefit many. Maybe slowing down could somehow allow for more to be said, for important stories to be shared, particularly those that center local communities and historically marginalized groups, with robust calls to action. Maybe if there was more time, it wouldn’t take an isolated and entitled, spectacular and satirical misfortune (but misfortune nonetheless) for all of us to sit and discuss.

Fantastic.

I wonder if it’s the commodification of storytelling or the subversion of story in the service of marketing that’s also part of the problem. The Tortoise and the Hare was created to express a truth. If the story were crafted in the service of the market, the hare would win because it wore Nikes. No wisdom imparted, just a vehicle to create a sale.