One of the few detriments of living in a city is the inability to find complete and unadulterated quiet. This comes as no surprise, as one of the draws of a city is the opposite: the near-constant buzzing of sound - a continual reminder that one is surrounded by life at every turn. The truth is that it’s quite impossible to find complete quiet in this world, even in places that lack that humming, bustling urban quality. When I return to my childhood home in the suburbs, I come close to finding it, but it’s never quite there. The stream of silence is always broken by some indiscriminate noise - the pecking of a woodpecker, a lawnmower, the engine of a FedEx truck. There’s only one instance I can actively recall, in which I came close to experiencing total silence.

I was in eastern Washington State, hiking through ankle-deep snow with my family’s dog in tow. After trudging uphill for quite some time, we came upon a clearing of smooth, untouched snow, the bright mid-day sunlight muddled by bloated grey clouds, threatening to spill more soft snow on the distant mountain slopes. I paused my trek and stood squarely in the aggressive quiet - even the dog seemed to sit still to take it in. There was no buzzing of people or disparate cries of animals, all the insects of the summer gone dormant or dead. The thick layer of snow seemed to insulate any sounds from reaching my ears, like a heavy wool blanket thrown atop flames. There is something so forceful - so jarring - about this kind of quiet, it feels almost frightening. The absence of something so familiar and comforting is so eerie it can send a chill down your spine. Most fetuses begin to develop sound in the womb at around eighteen weeks of pregnancy. They begin to hear their mother’s heartbeat, the sensations of the body - a constant, soothing hum that they grow so accustomed to that they struggle to fall asleep in the raw silence of a nursery once born. We grow to crave sound. And yet here I am, constantly searching for quiet.

If I were to categorize myself within the binary of introvert and extrovert, introvert would be most fitting. This is likely, in part, in response to my always being surrounded by people growing up. My childhood house only contained five people but seemed as though it was bursting at the seams with personalities - slammed doors, shrieks, and tears regularly bounced off the halls. Little sisters taking refuge in my room for days at a time after bad dreams and hard days. My bedroom became a kind of safe space, with a rotating cast of family members seeking advice and comfort from the eldest daughter. When I wasn’t at home - at school, at dance class, at work - people were present at every other turn. While I undeniably always had well-intentioned figures around me, the constant need to “show up,” to not be able to strip off my mask and sit alone - mind wiped like chalk off a blackboard - was exhausting. Even in the instances when “showing up” was to my benefit, I grew tired. The more time I spent around people the more it felt like the air was slowly being sucked out of the room.

I learned to seek my own kind of solace, not in others, but in solitude. I’ve never understood how people struggle to spend time alone - to me, it’s the greatest luxury, and I suppose I take an embarrassing amount of pride in that. There are few situations more ideal than a night in by myself, cooking a painstakingly complicated and time-consuming meal, making a glorious mess in the kitchen, and then retiring to rot on the couch in front of the television, the bun in my hair sliding down to my ear. Or to have an afternoon out by myself, picking up a pastry from my favorite bakery and heading to the park, a book underarm. Or to simply walk around my neighborhood in the company of myself, nodding and smiling at my fellow passersby, pretending like I have a destination in sight and have people to see.

Once you learn to love spending time alone, you risk developing a kind of addiction to it. For one, there is virtually no risk involved - no possibility of embarrassment or awkwardness in front of someone else. You don’t have to worry about saying the wrong thing - or someone else saying it - or about seeming too boring or uninterested in the conversation. There’s no fear of how you’re being perceived because nobody is there to perceive you. It feels like some sick and twisted way to hack life, a surefire way to bypass disappointment, shame, and heartache. I fear it’s an addiction I’m on the brink of.

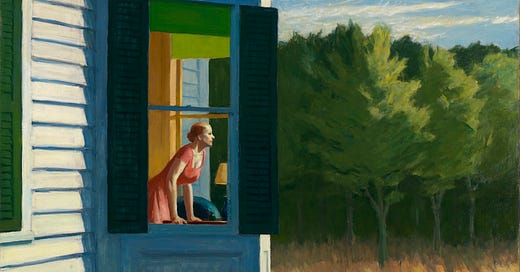

My addiction to solitude reaches new heights the further I slouch into adulthood. Rather than the fear of missing out, I often experience the fear of an invitation, disturbingly reveling in canceled plans. I’m like some mad woman in a shuttered-up house, peaking out the blinds at her friends outside, hoping that they don’t forget about her, even though she doesn’t offer as little as a return text message. I’m often worried that I’m a bad friend, which is a worry that can, of course, be alleviated by simply being a good friend - by showing people that you’re thinking of them, by making earnest attempts to spend time together. But when the intoxicating nature of quiet and solitude grips its claws in me, it’s a tricky trance to break.

Self-proclaimed self-help and lifestyle gurus on social media boast the benefits of learning to enjoy spending time alone and taking yourself on solo dates, not being afraid to reserve a table for one, or attending a concert in your own company. The proliferation of that kind of encouragement reminds me that I’m laughably in the minority, the camp that somehow feels emotionally and socially stunted, needing a shove out of the nest rather than a call to return home to oneself.

It’s no one’s fault but my own that I feel Frankensteinian - if I were fully secure with my alone time, there would be less unease. I don’t think there’s a problem with people enjoying time by themselves. But I think what I’m discovering about spending too much time alone is that it’s a kind of numbing salve, rather than an invigorating habit. Sure, it prevents the negative affection that sprouts from bumbling interactions, but it also blocks the bliss that comes from making a genuinely pleasing connection with someone else. Or creating what you realize will be a treasured memory with a loved one when you’re in the middle of creating it. On the one hand, it’s a shame that few rewards come without risks. But if those rewards came easier, they would be far less enduring. There would be far fewer relationships that feed our souls in the unique ways they do.

I think it’s just fine that I often feel most comfortable in the quiet - it’s simply a part of my personality. I’m lucky that I can stand my own company for as long as I can. And I know that fear is worth swallowing for the chance of a warm encounter with a friend. I can sit inside, eat my food, read my books, and stare out the window until I fall asleep. I can lock myself away from others, holding back the beast for their own sake, or shut others out in the name of self-protection. I can play my solitaire from time to time, but I can’t deny that relying solely on solitude bars one from experiencing the effervescent highs and the unsettling lows of human interaction, all of which are necessary to live a far more interesting and fulfilling life. Just as I realized ankle-deep in snow, the quiet can be comforting and grow frightening. I will always cherish my own company. But I’m better off when I don’t lead this life completely alone.

I drew a lot of inspiration for this piece from my own lived experience and the essay “no good alone” by (down to the inclusion of an Edward Hopper painting). I highly recommend reading her work if you haven’t already.

“There are few situations more ideal than a night in by myself, cooking a painstakingly complicated and time-consuming meal, making a glorious mess in the kitchen, and then retiring to rot on the couch in front of the television, the bun in my hair sliding down to my ear.” so true!

Enjoyed this piece as I have many others. At 82 (soon to be 83 ) this month I feel blessed

to have high tech hearing aids. Solitude is easy to achieve by simply removing the hearing aids. It instantly gets very very quiet, wherever I am. Trying to sleep, on an airplane, at a rock concert, around screaming kids, or wherever. Thanks for your insight.