At fifteen, I marveled at the click-clack of heels on tile floors. I wore the strained arches and blistered heels like blue ribbons. The hair was singed from curling irons and the dresses were ill-fitting. I took pride in my age being overestimated, in baring as little resemblance to my elementary school self as possible. In my twenties, I revel in the agelessness of a slouchy pair of jeans and in the ease of moving about life free of excessive adornment. If you compare pictures of the two selves, it may be challenging to discern which is the adult: the accessorized child tripping in her too-big shoes, or the acne-clad grown-up with holes in her socks.

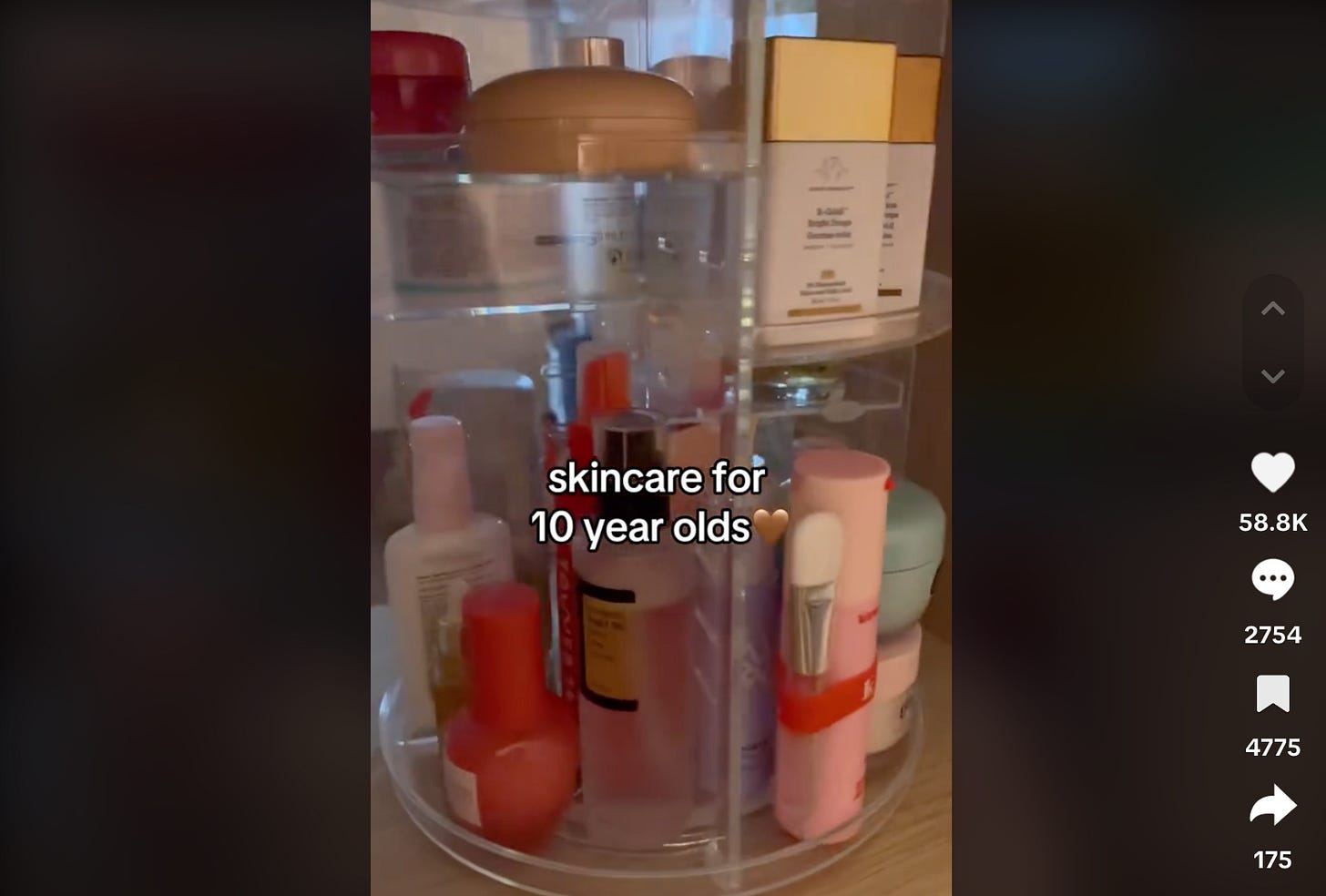

This past Christmas season, there was much discussion on TikTok and Twitter about what kids want as gifts these days. Elder zoomers and young millennials, drunk on nostalgia, reminisced about seeing a Nintendo DSi or Wii under their tree in the 2000s and 2010s. People deliberated the wishlists of today’s children and tweens on TikTok, as many cited expensive skincare and makeup as top priorities.

There’s always been some general head-shaking at the speed at which children are growing up, influenced by an entertainment-obsessed culture that depicts tweens and teens as far more mature than they actually are. At present, this phenomenon co-occurs with young women online embarking on missions to connect with their “girl” selves - whether it’s tying bows on everything, returning to the popular media of their childhood, or pasting the word “girl” in front of ordinary life happenings. All in all, the incidents are summed up well in this tweet from Twitter user @chloeikennedy that reads “grown women participating in a trend to seek a perpetual state of girlhood… preteen girls asking for drunk elephant retinol cream for christmas…”

In short, girls are trying to appear more like women, and women are trying to appear more like girls. The latter is a trope that’s been laughed at in copious pieces of media, whether it’s the frozen faces of Real Housewives or Regina George’s mother in Mean Girls (2004). In dramatized depictions, the youth-hungry woman often manifests in the form of a jealous, middle-aged mother - think Mother Gothel from Tangled (2010). Nonetheless, the age at which women are beginning to feel physically lacking seems to be decreasing, as more and more twenty-somethings flock to clinics for preventative filler, getting a kick start on slowing their skin’s aging as early as their school graduation. The zeal for early self-preservation paired with enthusiasm for youthful media, clothing, and proclaiming oneself a “twenty-something teenager” indicates a slight anxiety about aging, or at the very least a romanticization of one’s youth.

The other, ironic side of the coin features teenagers - girls, in particular - attempting to make themselves appear more mature than they are, incorporating “anti-aging” into their skincare regimens and conducting multi-layered makeup routines. This phenomenon is accompanied by popular media like Euphoria (2019-) that depicts teenagers engaging in heavy drug use, graphic and at times, violent, sex, and getting entangled in complicated relationships - all of which are more characteristic of adult life (more on that in this article).

The question isn’t whether this shape-shifting is happening - that’s for certain - but rather when it begins. There isn’t an exact moment I can recall when my desire to take up space sharply pivoted to a need to shrink. For so long, I felt too young and, then all at once, old. When that transition happens is likely dependent on the individual and their personal experiences. Regardless, it seems as though every generation believes that the one following it is aging at a more rapid pace than theirs did. I remember being a girl “growing up too fast” and now I’m tip-toeing across the threshold, now the one shaking my finger at those darned kids and their phones. Now the one trying to remember what it was like to be a child.

Technology and the accessible nature of public speech and information exchange are certainly making it seem like current generations of kids are growing up faster than past ones. However, when analyzing “traditional” markers of maturity - when one gets their driver’s license, has sex, tries alcohol, goes on a first date, gets their first job, etc. - it’s clear that kids are growing up slower than they once did, pushing many of these “first” experiences into young adulthood. What we’re witnessing in popular media and on young people's social media profiles may better reflect their desires to grow up faster, than the material reality of growing up fast. Or perhaps, a different definition of “maturity” is needed to evaluate the matter, as what we define as “kid” and “adult” varies across space and time. For BBC, Katie Bishop posits that today’s youth are exemplifying what it means to look “mature in today’s world,” which may place a larger emphasis on technological aptitude and forming social connections outside of one’s hometown and local friendship circles. We may be living through a transition of sorts, as what it means to be “mature” changes in real-time alongside a rapidly changing world.

When questioning the consumption of girls and women, rebuttals often come in the vein of “Why can’t people just enjoy things?” An understandable question, as girls and women have long been mocked for what they enjoy, but one that can champion the consumer over the person. Matters of aesthetics - matters of “trend” - are harmless on the surface but can reflect certain realities of a time. I certainly think people should enjoy dressing themselves and deciding how to appear in the world. And it can be enlightening to consider how swaths partaking in either girl/woman monoculture may be furthering agendas set long ago, often without the intention to do so.

For example, what’s most interesting to me about these kinds of mini-moral panics about kids growing up too fast, grown women self-infantilizing, and the like is that they’re often positioned as brand-new conundrums. As phenomena sprung out of social media, which forces us to reckon with our self-perception. Tweets and headlines ask why girls suddenly want skincare instead of dolls and why women are referring to themselves as “girlies.” In reality, children have long stolen the lipstick out of their mothers’ vanity drawers and relished in their ages being overestimated. Women have long put their time and energy into home remedies to tighten their skin and winced when asked to recall their birth year. Very little about the anxiety women feel about aging is new - it’s been well-woven into cultures that consider youth and beauty powerful social currencies. When considered in another light, social media simply allows us to examine these experiences at both a greater distance and under a closer microscope. We can observe these familiar behaviors re-manifesting under different “trends” which establishes them as things that will eventually pass. But, as we’ve seen, they rarely pass entirely.

Adults tend to romanticize their childhoods - comparing the children of today to rosier versions of their own pasts. And how could they not! Chances are, their childhoods were far more carefree than a responsibility-ridden adulthood. But the glossiness skews comparison - chances are, their parents were thinking the same thoughts as their children adopted the cutting-edge trends and technology of the time, growing up in a manner that felt far more accelerated and challenging to define. In short, it’s likely always felt like kids have grown up fast. In reality, a re-definition of what it means to “grow up” may have been what made the experience feel so jarring. That may be what’s happening today.

As such, young girls’ obsessions with womanhood and young women’s obsessions with girlhood, while stark at present, aren’t so dissimilar to behaviors that past generations have exemplified. Social media, with its focus on appearance, may heighten these behaviors, as well as simply bring them into sharper focus, better available for us to observe and pick apart in the palm of our hands. All in all, what’s clearest to me is that girls are better off accepting the learning and support that comes with embracing the temporary state of girlhood, while women are better off wholly accepting the responsibility and independence that comes with being adults - regardless of how they choose to dress. Bows, heels, baggy jeans, and all. Nonetheless, the ability to fully embrace either identity is challenging when both feel so in flux, when the lines between the two continue to blur, and when either demographic is taught to want what the other has.

For more writing on a similar topic, I recommend my article The Twenty-Something Teens, as well as Women in Retrograde by Isabel Cristo and “Girl” trends and the repackaging of womanhood by .

My girlfriend and I were just having this discussion because she's a teacher and directly sees this early obsession with anti-aging among young girls. Something that socially liberalized culture and technology do in tandem is show our revealed preferences since we are all given near-maximum freedom to do whatever we want. Whether those preferences are biologically natural or culturally learned is besides the point because either way, we end up with pre-teen girls already worrying about wrinkles.

This type of behavior is to be expected in a youth-obsessed culture, and much of the gender wars between men and women come down to which gender gets the privilege of staying/behaving young longer. For instance, the increasing rage against age gap relationships, even among fully adult men and women, is at least partially fueled by women's anger that men get to act younger longer. The fury over abortion and birth rates is also tied to this because parenthood, especially motherhood (due to the physical changes that childbirth brings, as well as greater social scrutiny on mothers than fathers), truly marks the end of maintaining a youthful lifestyle unless one wants to risk harsh societal judgment. But somebody has to have children, and in a culture that is sharply devaluing having families and growing older, it makes sense that women deeply resent being born with a womb (which I also think at least partially motivates some cis het women's fervent support of trans issues, because of their interest in wanting to separate the definition of womanhood from biological childbearing).

I think the intersection of social media and capitalism has played a huge part in today’s teens -- particularly young girls -- obsession with looking older or having “older” interests. Since it’s commonplace now for middle and upper class teens to have their own iPhone, they can download Instagram and TikTok, where they’re constantly exposed to ads (whether it be a straight up ad or a haul or get-ready-with-me, etc.) for makeup and clothing that adult women wear. Whereas when older gen z and millennials were growing up, we were just being introduced to smartphones and social media. The advertising we were exposed to was still pretty traditional so there was more of a disconnect, imo. We might have wanted to wear heels or borrow our moms’ lipstick but that was the extent of it because we didn’t have exposure or access to those interests the way younger girls do now. Especially if you factor in how many of these girls may also have access to their parents’ credit cards, it’s too easy for them now to see something they like on the Instagram shop tab and use Apple Pay. Whereas I had to beg and plead my mother for $20 to go and buy something at forever 21 lol. So I think, as you stated, younger girls have always wanted to look older and women have always wanted to look younger, but the big difference now is that we all have more access to items that help us do just that, so it appears as if today’s girls are skipping the preteen or awkward teen phase when really they are just being exposed to capitalism on a scale we never were.