What Makes You Think You Can Call Yourself a Writer?

In-Fighting, Calls for Editors, and Scarcity Mentality in Self-Publishing

You know the feeling. In July, when the sun is at its highest and hottest. When you eat your first bite of an ice cream cone. When you wake on Christmas morning to that sinking feeling that Christmas is already over, because Christmas isn’t actually the 25th of December, but the days and the emotions leading up to it. When the cherry blossoms have all bloomed and the wind begins to shake their petals off.

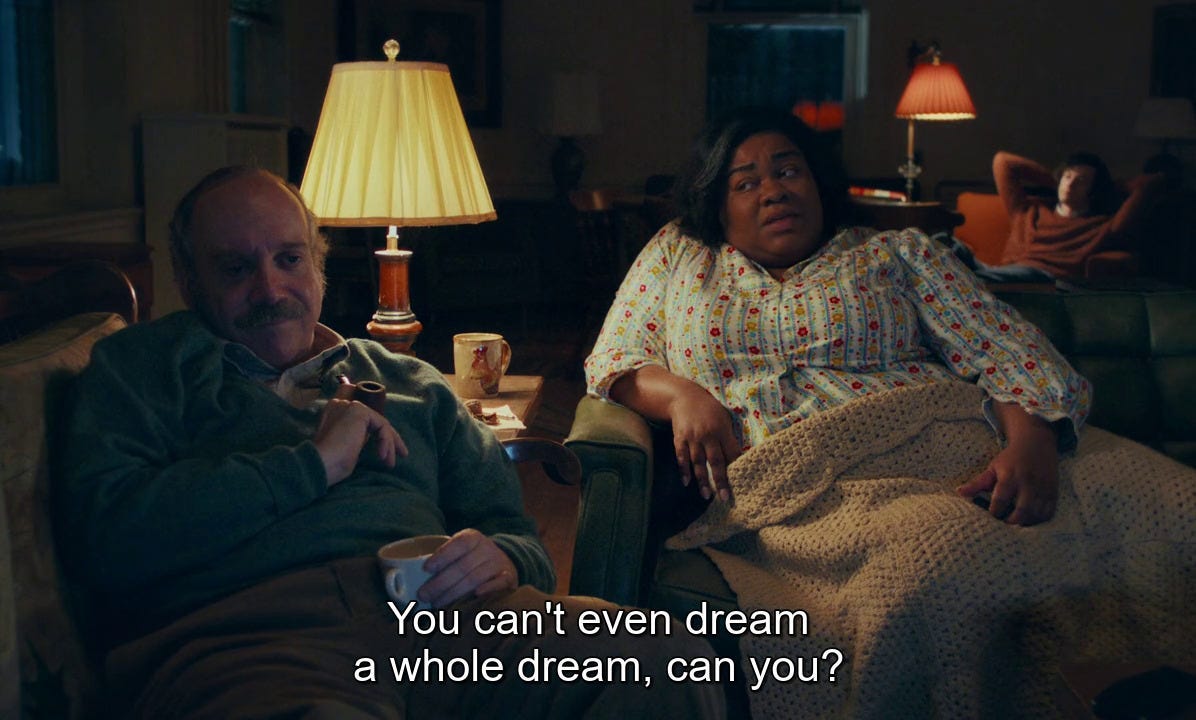

You’re sitting in the middle of a good moment and can feel it leaving quickly, relative to how long it took to arrive. You tighten your grip as you feel it slipping. If you could lasso the sun, if you could stretch time, if you could collect the cherry blossom petals and reattach them to their bud, you would, but that’s not the way of things. You can’t drink up the sunshine forever. Eventually, the moon needs a turn.

I know the feeling. I remember it when I was starting my first job and settling into my apartment in New York. My desk faced a wall in the living room, I knew zero Excel shortcuts, and about fifty people read my writing, but I felt rich. I remember sitting there, drunk off independence, pressing Command + C and Command + V, and the feeling washing over me. The stalling - the air time - before the pendulum careens backwards.

It’s much easier to think of things as balanced instead of cyclical. The metaphor of a seesaw works better than a washing machine. The seesaw is inherently dramatic, there’s some suspense involved. How long will you stay airborne until you’re thrust back down? It’s quite an individual image. You sitting singularly on one end, the opposite side weighed down by a shapeless black ball of energy, an entity with unpredictable moves. The washing machine has no glamour. A mishmash of sopping wet clothes, getting tossed around and around. Monotonous, predictable, boring.

Not knowing where you’re at in the cycle is frustrating. You can usually discern a big win from a crushing loss - the stuff in the middle is what gets muddled. For the past couple of months, I’ve had this suffocating feeling of being on a precipice. My toes gripping the ledge, my eyes looking up at the light, a sneeze building in my nose. In a movie of my life, the past couple of months would be a montage. Career, creativity, and morale in a place of neutrality. Time-lapsed, fast-forwarded before the next moment of salience. I just don’t know if that moment is going to be a peak or a valley. I don’t want to jinx myself. But if I were to draw wisdom from experience (and give in to my cynicism), I’d say that things often need to get worse for them to feel better. My best night of sleep usually comes right after a night of tossing and turning.

This mindset favors the seesaw metaphor. It also favors a model of scarcity. The idea that everyone needs to get their turn of suffering and triumph in equal measure. The tallies of wins and losses remaining even, one after the other after the other. A clean pattern.

I think people either naturally lean towards an attitude of abundance or an attitude of scarcity. I am definitely the latter. As a kid, I would ration all of my desserts, making sure my pint of Ben & Jerry’s would last the whole week, ensuring a chunk of cookie dough in every bite. My supply of Halloween candy survived Christmas, stretched into the new year. Every time my parents dropped me off at an extracurricular activity, I was sure that they wouldn’t pick me up, for no good reason. I can’t help but say all my goodbyes with a seriousness in my eyes and voice, for no reason other than that I’m waiting for the other shoe to drop. For no reason other than this dread that I’m lacking misfortune.

I’ve always worried that good things are in short supply for me, even though the truth is far from that. I’m quite fortunate to have been dealt the hand I have. Living with an attitude of scarcity is living with an attitude of tempered expectations. Of envisioning dreams that can only grow so big, until they press up against a glass ceiling of your own design.

Last weekend, I was hanging out in a small group of people and was asked what success looks like for a writer. One other person in the group was a writer - the two of us locked eyes, searching for an answer in the other person’s stare. There’s, of course, the J.K. Rowling version of writer success. Being the creator of timeless intellectual property, to be reinterpreted via blockbusters and theme parks. To have an untouchable level of notoriety, enabling you to espouse whatever beliefs you want, protected by your nine-figure net worth.

That’s what success looks like for the most successful of commercial novelists. Success for an “essayist” is measured by a much smaller metric. Perhaps an essayist has “made it” when they no longer need to be supported by a day job, when they’re able to make money solely off their words. Perhaps they’ve made it when they’ve accrued a sizeable readership, when notable writers cite their work. When they’ve cemented a distinct voice, when they’re often imitated but never replicated. For some, success as an essayist is measured in the courage one has to put pen to paper, to be brave enough even to share their words.

Writing is a fickle institution. Like much of the arts, it’s a practice that is gatekept with iron locks, only for one to get past the guards to find that the great practitioners are making pennies and remaining beholden to “restructuring.” I’ve had conversations with friends and acquaintances, many of whom are writers or are interested in the practice of writing, who have asked me what the “goal” of my writing is. Many ask if I one day hope to write for a legacy publication. Or they assume that writing for a legacy publication is my goal, and begin spewing advice.

Perhaps it's that cynicism rearing its head again, but when I’m asked what I hope to accomplish through my work, I hear it as Why do you think your words deserve to be read? Why do you think you should take up the space? Entering spaces with “professional” writers can feel like a game of competitive musical chairs, especially amid a recession. It feels like there’s only so much space.

Some writers I know, who don’t have active newsletters or blogs, have told me that writers shouldn’t start their own ventures until they’ve worked many years under the eye of a wise, scrutinous editor. These people tell me they’re excited that young writers feel emboldened to “start their own thing,” but that they should go through the “traditional” circuit of writing for bigger and bigger legacy publications before they feel confident enough to untether themselves and write as a free agent. A lone ranger.

The extreme interpretation of this perspective harkens to the idea of writing being a “grand mythology,” which Rayne Fisher-Quann has written about at length. The idea that “writers are monsters, gods, saints, freaks, mystics,” and hone their craft through sacralized rituals and apprenticeships under seasoned professionals. The idea that you can’t practice the witchcraft of writing on your one until one of its gods has granted you permission.

The truth is that tradition has collapsed. Legacy publications are downsizing. Staff writer positions are near obsolete. Copywriting and copyediting are being outsourced to AI. If you keep waiting for the chance to write under a professional editor, you will be waiting for a long time. Former Outside Magazine editor Isabella Rosario offers a balanced perspective on the belief that writers on Substack - a platform for self-publishing - need editors. Rosario argues that most writers would likely agree that having an editor review their writing would improve their work. But under current macroeconomic conditions, writers waiting around for an editor to shepherd them before they begin creating likely won’t write at all.

“I have a hunch that when people say writers need editors, their sentiment is more of a dunk on writers than an endorsement of editors,” Rosario writes. “Having read what they consider ‘bad’ writing, they don’t just think it’s bad; they deem it unfit for public consumption…Saying ‘writers need editors’ at a time when there are so few editing jobs and freelance rates have remained stagnant for 25 years is very ‘Let them eat cake.’”

Older generations naturally get a sour taste in their mouth watching youngsters skip the line, speeding past “traditional” processes in favor of a fast-pass to viraldom via blogging. This view is understandable, but it also has roots in a scarcity perspective. With seemingly fewer professional writing opportunities available, writers naturally turn scrappier. They look to police one another, making sure the most “worthy” and most “qualified” candidate gets the golden goose, which is invariably the candidate who’s been the star student. Who has followed the appropriate steps in the appropriate order, never inflating the value of their words by assuming they have something to say without someone older and wiser passing their eyes over it.

Scarcity is what’s driving a lot of the in-fighting and indirect shade-throwing on Substack Notes. A scroll through one’s Notes feed is like a walk through a high school cafeteria. There are only so many paid subscriptions a reader can commit to, only so many book deals to be handed out to amateurs. It’s a mushy, lovey-dovey app, with a quite cutthroat underbelly.

In her essay “Choosing to walk,” Fisher-Quann writes that employing AI tools to beautify and edit one’s writing alienates writers from the aspects of writing that are grueling - building an argument, thinking through syntax, putting fingers on keyboards, etc. - leaving writers with the sole, romantic task of “ideating.” Separating the mysticism of ideation from the strenuous task of actually writing estranges writers from the fruits of their labor, creating distance between themselves and their work. And, ultimately, it doesn’t make them stronger writers.

Strangely, I think this relates to the idea of choosing to write without the pedigree that an English degree or staff writer job breeds. The only way to improve as a writer is to write. Fisher-Quann argues that practice is what has materially made her a better writer, explaining that writing is a “muscle that anyone can develop and that anyone can let atrophy.” It isn’t enough to let the ideas rattle around in your head until an editor agrees to look them over. You will never know what there is for you to improve upon until you put words to page. And when this mythical editor does come to fruition, you will need work to show them.

I’ve seen writers on Substack peer edit each other’s work. I also know of writers who make enough money self-publishing to afford an editor. Before one can have any of those things, they must embark on the painstaking task of addressing their own work, and ramming against the limitation of their abilities. Progress is usually slow and marginal, but it can take many forms. Fisher-Quann lists examples of numerous sites where one can practice the task of writing: homework assignments, work emails, text messages, and personal essays that no one reads. Adopting a line from Rosario’s piece: “it’s writing all the way down.”

I haven’t had a meaningful professional writing job in my adult life so far, and I’ve often found myself spooked having conversations with those who have. It’s not exactly imposter syndrome I’m experiencing, so much as it is the plain fact that I am an impostor. Each week, since I started self-publishing three years ago, I’ve attempted to deceive my readers into thinking I am a writer. Evidently, after three years of writing (some awful pieces and some I’m quite proud of), there’s no need for deception any longer: I am a writer. The future of media is hazy and unstable, but I’m trying my hardest to push against the idea that it’s scarce by carving out a tiny space for myself to improve upon my work. And I’m not doing it because of a co-sign from a higher power. I’m doing it by putting pen to paper.

As someone who's read your stuff since I started on Substack, it's been great seeing how you've kept at it and grown!

Another important thing about not having editors is learning to self-edit. When I was reading The Vanity Fair Diaries for a recent piece I wrote, I was surprised to learn that some esteemed writers would just send in notes/scribblings to magazine editors, who'd then have the responsibility of actually turning those into readable pieces.

Complete freedom will certainly lead to excess and laziness on the part of writers. But that's also what writer friends and audience feedback are for. And yes, an official editor now and then is good, as all intelligent feedback is. But over-idealizing rigid editor-writer relationships, especially these days, is more like gatekeeping by those who know they're on the inside and want to protect those hard-won advantages.

you’re such a generous reader & writer. The scarcity mindset in publishing that you describe is understandable—shit’s bleak—but it’s just not useful. here’s to putting pen to paper<3