Your eyes flutter awake as the wheels touch down on the tarmac, rumbling the plane cabin awake. The window shades are down, and the light strips along the aisle floor give off a soft lavender glow. The Delta flight attendants welcome you to Seattle, Washington, where the local time is 7:10 AM. Everyone is rubbing their eyes and yawning as the plane taxis into the gate.

The lights in the cabin grow brighter, and before you know it, a “Ding” emanates from the ceiling, indicating that you can unfasten your seatbelt. As people begin shuffling through the aisle, grabbing their suitcases and shaking their children awake, music enters the airspace. This music is unlike anything you’ve heard on hold with Amazon customer support or in the dressing room at Old Navy. This isn’t the usual bubblegum pop, soft new age tones, or innocuous jazz that typically fills common public spaces. No, the Delta Airlines deplaning playlist is something else entirely.

As passengers yank their carry-ons out of the overhead bins and push down the aisle to make their connecting flight, a forlorn, heartbroken man croons throughout the cabin. He sings about how much pain he’s in, how his heart is bleeding on the floor, while his apathetic ex-lover saunters away, having just stomped on it in high heels. There is no cheekiness in this music. There is melodrama, but it’s not the kind that you would hear in a Celine Dion ballad. It’s devoid of anything other than emotional wretchedness; there is no strength, no sense of resilience, no ounce of beauty in his pain.

You are already exhausted from travel, but this music somehow emphasizes that, slipping a few bricks into your backpack. You wonder who on Earth hurt the Delta employee in charge of making this playlist so badly that everyone on every Delta flight needs to suffer in perpetuity. You exit the plane, pop in your earbuds, and begin playing literally any other artist.

This has been my impression of popular, contemporary male singers for quite some time. If you scroll through my music library, straight male singers born after 1995 are largely absent. New male pop stars and singer-songwriters are hard for me to get on board with. I understand that men can experience heartbreak and emotional distress in romantic relationships. I’ve just often heard them sing about it in clumsy, self-victimizing ways (Lewis Capaldi, Benson Boone, etc.) or in ways that lack verve or personability (Shawn Mendes, Charlie Puth, etc.), or in ways that sharply contrast the way they treat women in their public life (John Mayer, Drake, etc.). In my own life, I’ve witnessed men cause much of the pain in heterosexual relationships, and I’m also cognizant of the upper hand men have in a misogynistic culture. I’m certainly approaching their kind with a bias. It takes a lot to win me over.

This is why I didn’t find myself in too much of a bind at the Friday sets at Outside Lands 2025, a music festival in San Francisco, California. On Friday, at 7 PM, Doechii, the artist I bought the festival tickets to see, was overlapping with Role Model, a twenty-seven-year-old, straight, male singer-songwriter with a reputation for trolling online. The choice was obvious. I caught Doechii’s impeccable main stage performance, which was complete with clean dancing, imaginative set designs, and a glorious narrative throughline. Riding the high of that, my friend and I floated over to the second-largest stage next door, where Role Model was finishing his performance.

Based on his online reception, I got the impression that Role Model was revered for his charm and heartthrob qualities, as much, if not more, than his actual music, which I assumed was more bedroom-pop, SoundCloud rapper-esque. Thus, at this set, I was expecting to see a more pared-down version of what I had grown accustomed to seeing at One Direction shows growing up - hordes of young screaming girls bellowing the lyrics. Many assumptions were at play.

What I saw towards the back of the crowd, however, was a quintessential festival audience - quite mixed in gender, with a range of ages, but mainly late teens and early twenties. And this music wasn’t the kind that you usually scream. It was unmistakably indie-pop, but with a kind of folksy, Americana flair. He played a guitar and wore straight blue jeans with alligator boots. He crooned and spun on his heels. He swayed his hips back and forth. He brought out Troye Sivan as a special guest during “Sally, When the Wine Runs Out,” one of his hits.

But the lyrics were what really struck me. The first song I caught was a cover of The 1975’s “Somebody Else,” followed by “Old Recliners,” which features a simple Khruangbin-like melody and refrain about reminiscing on the past. “Thinkin’ ‘bout you, you in the moment,” the audience hummed gently. But the real standout was “Some Protector,” a true-blue heartbreak anthem that builds to an emotional deluge of a bridge. “Yes, I am and I always will be some protector / Some protector to you,” he cries in the chorus.

Role Model’s lyrics are self-critical without feeling gratuitous, and emotionally mature, without feeling stilted. He exists in a careful grey area, taking ownership of his wrongdoings and grieving what once was in equal measure. The songs are devoid of excessive vanity, at least on the surface. Against my better judgment, I’ve been listening to his sophomore album Kansas Anymore, a lot. There are a few skips for me (“Scumbag” and “Superglue”), but it’s an otherwise easy, sweet listening experience - a successful second album in my eyes. The country angle doesn’t feel contrived, and when contrasted with his online personality, actually somehow makes the charade all the more charming.

And I’m not alone - at the time of writing, Role Model has over eight million monthly Spotify listeners and over one million Instagram followers. Many are dubbing him a “yearner,” which is a badge of honor in a boisterous culture. A culture that often prizes those with loud charisma over quiet charm.

In a recent angel cake essay, Emily North pondered the difference between “charisma” and “charm,” dubbing the former a more punchy display of confidence or wit, typically deployed for romantic or sexual conquest (“rizz, swag, game, ‘it’”), and the latter an outpouring of warmth and generous attention. In a club reticent essay on cultivating charm, Valerie posited that charm is derived from radical honesty, genuine curiosity, and a desire to like others, writing:

“Charm is not navel-gazed, but generated through your radical, loud embrace of both honesty and openness rooted in liking people enough to generously hand a piece of yourself to them.”

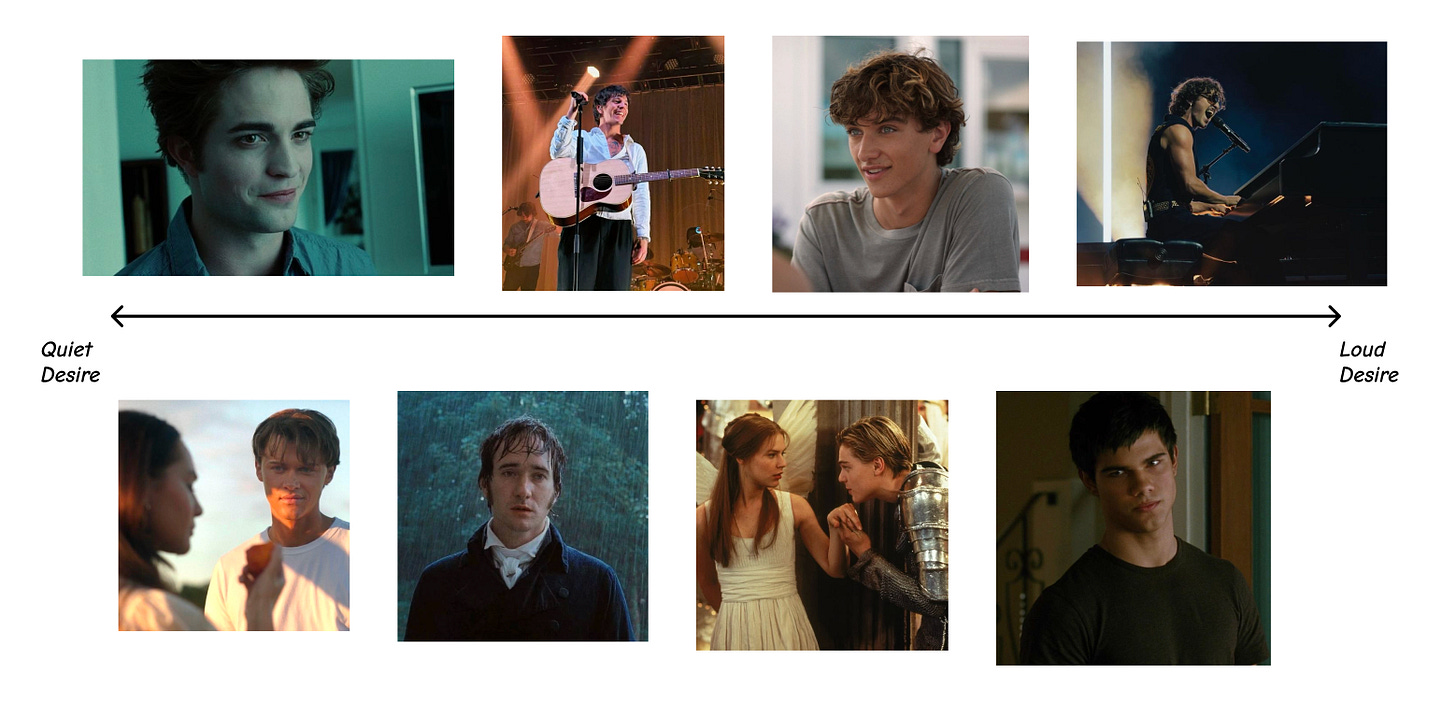

“Yearners,” in literature and onscreen, are revered for their more controlled displays of affection over noisy disclosures of desire. Like Valerie’s definition, this charm is embodied through the act of caring for someone to a degree that one is willing to sacrifice one’s own happiness. In many works, this manifests in the yearner’s acceptance of pain, and even banishment, often to their own detriment, and to the benefit of the object of their affection. Romeo skips town, Mr. Darcy doesn’t own up to his good doings. Edward Cullen runs away when he realizes his presence will only put Bella in danger. And, most recently, Conrad Fisher, the favored brother in the series The Summer I Turned Pretty, estranges himself from his family to keep peace with Belly, the love of his life, who’s marrying his brother (Austenian, I know).

Fictional brothers Jeremiah and Conrad Fisher, who are two-thirds of the love triangle in TSITP, are an interesting example of this dichotomy. Jeremiah is the flirt, the life of the party with big, expressive emotional swings, the “golden retriever.” Conrad is the thoughtful, introspective “black cat.” The former being hated and the latter being favored by the masses - as well as the endurance of Mr. Darcy, and Edward Cullen, who is in many ways an interpretation of Darcy - indicates a preference for this more polite, restrained kind of devotion, at least on paper.

For years, “grand gestures” were cornerstones of romance. Flash mob proposals, public declarations, a hundred red roses at your doorstep. Something was promising about a person loving you so much that they shouted it from the rooftops. Social media posts for every birthday and anniversary. “Wife guys” were antidotes to the poison deposited by many years of “my wife” jokes, around the watercooler and on stand-up stages.

Today, grand gestures often leave behind a sour aftertaste, particularly among younger people. Perhaps it’s because we’ve seen so many highly publicized relationships - from Beyoncé and Jay Z to Try Guy Ned and his wife - become marred by infidelity. I also think Gen Z is quicker to associate intimacy with reticence, given how adept we’ve become at spotting “performative” behavior on and offline. I do wonder if this attitude is fostering a kind of romantic cynicism. I’m quick to assume that any nice guy has something to hide and that every grand gesture is intended to mask something.

If you’re a public figure - like Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce - love is a valuable commodity. Album sales, football game attendance, and surely stock prices rise and fall with the strength of your love. I think this is even the case on a more pedestrian scale though. The ability to give and receive love, or at the very least appear lovable, is a highly marketable trait - sure to impress grandparents, future friends, employers, and all other kinds of stakeholders in one’s life.

For all the benefits of appearing madly and securely in love - and thus, well-adjusted and emotionally in touch - there’s something even more romantic about restraint. I often think of the lyrics to Taylor Swift’s “peace” when a new (seemingly staged) paparazzi photo of her and Kelce is released. I certainly thought about the lyrics upon seeing the proposal photos, Swift and Kelce surrounded by roses, a dupable Ralph Lauren dress on her frame, an unattainable rock on her finger. “All these people think love’s for show, but I would die for you in secret,” she once sang.

Over the past couple of weeks, “performative male” contests have been popping up in major cities across the U.S., intended to poke fun at the type of man who leverages manufactured softness to attract women. Such men are thought to co-opt the monikers of a “yearner” - Hugh Grant’s tousled hair and bookishness in Notting Hill (1999), Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s artsiness and intellect in (500) Days of Summer (2009) - for the sole purpose of getting a girl, typically in the short term. Contestants have been arriving with tote bags, feminist paperbacks, iced matchas, and blasting Clairo in an attempt to best encapsulate this archetype.

How does one differentiate “manufactured” character from “authentic” character? How can one ensure they’re not getting duped? The truth is that all character is “manufactured” to some extent. All of our public-facing personalities are engineered to attract the types of people we want to attract, even on a micro scale. Such engineering grows more meticulous the more public-facing your personality is, particularly if you’re an emerging star like Role Model or a pop veteran like Taylor Swift.

Nuance lies in how much vanity is entangled in the performance. How boisterous one’s desires are. But the true differentiation most likely exists in the motive. There’s a difference between wanting people to like you - and having a lot to gain from it - and wanting to genuinely connect with people. Learning to read the difference between the two - in nonfiction and fiction alike - is key.

Feeling very in the know because I just read the angel cake essay on charm and charisma, read Valerie’s essay on becoming life’s personality hire, and now this essay, swoon. My trifecta of women writers.

Also resonated with the idea of how everyone has a public persona. I earnestly love to get to know people- however I also notice that in my very client facing job I am honing a specific personality that highlights and dampens different facets of my inner self.

Love ur writing as always <3

Absolutely captivating,this piece does more than just critique soundtracks or live performances; it also unpacks the emotional economy of vulnerability through music. The contrast between performative heartbreak and the quiet, authentic ache in Role Model’s lyrics highlights a deeper yearning for emotional maturity. It seems we’re collectively gravitating toward what Emily North refers to as charm,not loud charisma, but the understated, radical honesty that invites connection. Your writing captures the difference between being “seen” and being understood, and how that subtle shift can become compelling rather than contrived. In a world full of grand gestures and curated personas, your words remind us that sometimes the most enduring resonance lies in the rhythms of restraint.