I’d like to be all noble and say I got interested in writing because of a deep passion for storytelling, art, or the power of the fourth estate. I’d like to say that I believe in the potency of the written word in shifting opinions and igniting action. I’d like to say that I didn’t choose to write, but that it chose me, that it’s the most effective way I’ve found for communicating how I feel about the world. While all of these things reign true today, my love for writing did not start there. In reality, many passions don’t begin due to a deeply vested, soul-consuming zeal for something, at least not when you’re a kid. They begin because of the whimsical, cinematic quality of jotting something in your diary with a pink glitter gel pen. You write something down and suddenly it is something someone else can read. You’re a person - romantic and full - with thoughts that others can perceive and respond to.

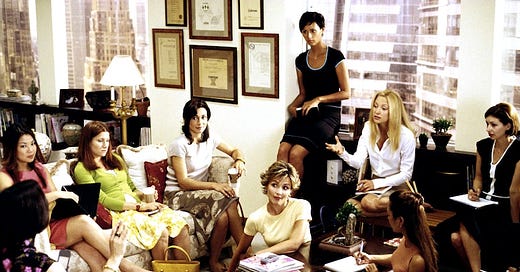

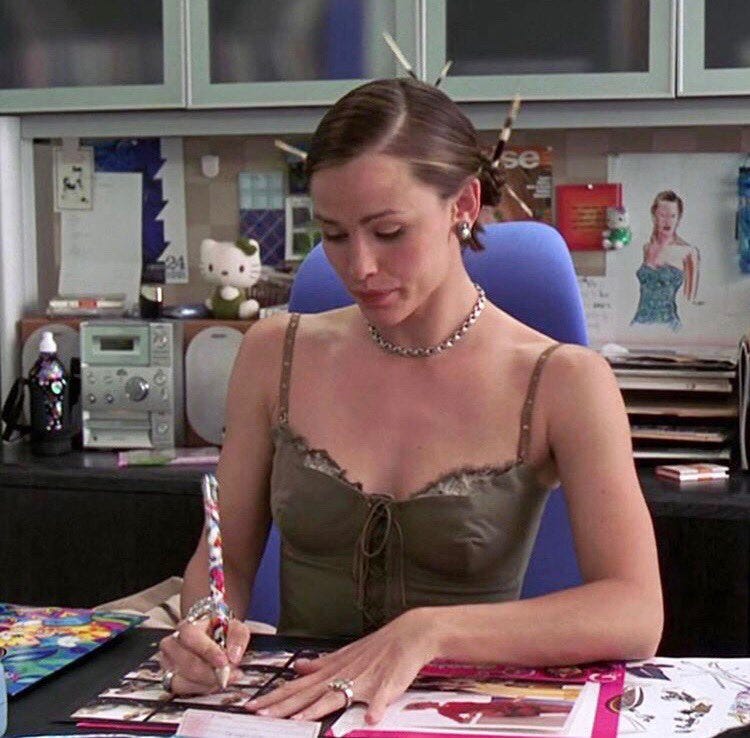

This fanciful feeling is matured and intensified when consuming romantic comedies of the 1990s and early 2000s, in which just about every woman protagonist has what appears to be the most glamorous job in the world: journalist. New York City develops a kind of magnetism, an allure fueled by the image of a young, beautiful woman running across concrete in designer stilettos, coffee tray in hand, flip phone squeezed between her cheek and shoulder, calling out “Taxi!” with a manicured hand raised, heads around her turned. You don’t have to open your eyes too wide to find her: Andie Anderson in How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (2003), Jenna Rink in 13 Going On 30 (2004), Andy Sachs in The Devil Wears Prada (2006), and of course, the ever iconic Carrie Bradshaw in Sex and the City (1998-2004).

They have their mutations, of course, some may not be traditional journalists in practice, but rather columnists and editorial assistants. Many of them dream of writing “real” stories about things that matter; typically gritty pieces about foreign affairs and domestic politics, topics that aren’t as sexy as the writers’ exteriors. Others desire to reinvent and innovate in the glamorous spaces they currently occupy. All are fueled by daily lattes, company galas, cosmopolitan soirees, and a workload that’s the lightest of any working writer I’ve met in the real world. The gigs, men, and designer clothes come to them as easily as the day passes into the night.

I learned rather quickly that writing was a skill I was drawn to. In school, my brain’s gears ground and sputtered hard in math class, but in English, they flowed like a well-oiled machine. It was clear that processing ideas through reading and writing was one of the ways I could understand complex matters most effectively. I quickly took to reading chapter books in kindergarten and would write fictional short stories with accompanying illustrations. I became so enamored with the ritual of reciting a story that I insisted on reading the same picture books again and again to my parents and grandparents until the words were memorized and imprinted on my inner eyelids whenever I went to sleep. I attempted to write songs and poems and was later taken by writing essays in high school, my chest filling with elation when I was able to capture my thoughts effectively on paper.

Naturally, as most students are encouraged to do, I began to ponder how I could turn my knack for writing into a career. And it didn’t take too long for me to surmise that the most fulfilling job for someone who enjoyed writing would be “writer.” When I began to “come of age,” so to speak, my desire to become a writer was undoubtedly energized by the air of cosmopolitan excitement surrounding my favorite women journalist rom-com leads. I began dreaming dreams of Manhattan, of parties in gowns with champagne flutes, of raising my hand in a crowded newsroom - pencil tucked behind ear - and exclaiming an idea that others nodded in agreement upon hearing. I imagined sitting behind a desk or cross-legged in a coffee shop armchair - mug in hand, hair tossed into an imperfectly perfect updo - and typing up a story that would garner mass readership, acclaim, and affluence as soon as I pressed the ambiguous “Publish” button. In short, I dreamed about the idea of being a writer - or at least, Hollywood’s idea of it.

It’s not too challenging to determine why so many onscreen women leads are journalists. Writers - including those for the big screen - often write about what they know, and what they know is a lot of people that work in media. And journalism isn’t just something that media professionals are familiar with - the public is in close contact with the industry’s output. They consume profiles, exposés, and investigative pieces. They follow the unfolding of political and cultural scandals via articles, watching with bated breath as the press fulfills its watchdog role, popcorn in hand.

While women were barred from entering most professional industries throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a result of systemic sexism, journalism, media, and various art-adjacent sectors are perceived as some of the first to permit white women participants. This is at least the popular Western cultural conception, based on the vast acknowledgment of astonishing singular characters like late nineteenth-century investigative journalist Nellie Bly and fictional tales of mid-century wordswomen like Hildy Johnson in His Girl Friday (1940) and later Peggy Olson in Mad Men (2007-2015). Such characterizations helped bolster and pave the way for the Andie Andersons and Carrie Bradshaws of the onscreen world, accompanying the assertion of journalism as an industry that benefits from women’s “disruption” and the unique perspectives imparted by those notoriously branded as “other” or “less than.” Pair this activist perception with the often-times contradictory glamour of Manhattan nightlife and the wealth of legacy media conglomerates, dished out in sparkly 2000s rom-coms, and a dream job is implanted in the brains of girls nationwide.

Could there be a problem with this then? Second-wave feminists went to great lengths to convey the necessity of financial independence for women’s liberation and the importance of permitting women the chance to pursue a career outside of stay-at-home motherhood. Girls should be encouraged to chase passions that contribute to their personhood and to the world they live in, particularly journalism where only 22% of the top news media editors are women.

The issue arises when looking at the chasm that is the pay gap between onscreen women journalists and those in the real world. At one point in Sex and the City, Carrie Bradshaw famously writes for Vogue for $4.00 a word, which amounts to $2,000 for a 500-word essay. According to Indeed, the average salary for a journalist in the United States in 2023 is $49,000 and caps out at around $83,000. And a 2016 report from the Equality and Human Rights Commission shows that men are earning, on average, 9.4% more than women for doing the same job in the field.

This isn’t to say that journalists need to be rolling around in excess, indulging in weekly thousand-dollar shopping sprees and jetting off to international galas every weekend - but they should be compensated properly, with benefits and with the ability to give a fulfilling life to themselves and their families.

I find it interesting how the onscreen women journalist industrial complex has skewed the public’s perception of writers and metropolitan living. In actuality, writers are often carrying hefty workloads, meeting tight deadlines, and often just getting by financially, if at all. Living in a city is beautiful and buzzing, and also expensive and, at times, alienating when one flocks there from a community they know like the back of their hand, in hopes of bigger and brighter things.

These realities are rarely presented in women-targeted media featuring journalist leads. But do these truths need to be mentioned? Isn’t the silver screen supposed to be a place for fantasy? As Nicole Kidman famously says, “we come to this place for magic” (this place being the movie theater, of course). Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for imagination - one of the joys of media is its escapist qualities. Nonetheless, romantic comedies have certainly laid the groundwork for a blending of fantasy and reality that’s been exacerbated by social media and the tendency to romanticize one’s life on it.

If our dreams are rooted solely in a Pinterest aesthetic or the feeling of being conventionally beautiful, they are dreams that will only ever be fulfilled in fleeting moments. When dreams are drawn up from such surface sources, they result in “Harvard Law School” mood boards, featuring beautiful brunettes drinking coffee and looking over nondescript textbooks, sweater off the shoulder, revealing a slender collarbone. They result in the Caroline Calloways of the world or writers who love the image of a writer more than the practice itself. They result in appearance over substance. They result in an industry that will gladly ask you to perform complementary or poorly compensated work because you should feel so lucky to even have access to such a glamorous world.

Joan Didion writes about similar themes in her 1972 essay “The Women’s Movement.” Discussing the problem with any action a woman performing being considered “feminist,” Didion writes that women who follow such doctrines “want not a revolution, but ‘romance.’” They “believe not in the oppression of women, but in their own chances for a new life in exactly the mold of their old life.” Didion doesn’t believe in empowering oneself through individual conceptions of capitally-defined self-actualization, as many of those conceptions are hollow and only influence the singular. I take it that she would consider dashing to a city, a person, or a job out of vanity similarly hollow. Ambition without substance is barren.

I suppose, in many cases, we can only become interested in something because of how it appears on the surface. And sure, it feels good to bask in the wonder of those fleeting, beautiful moments. This isn’t to discourage anyone from pursuing a career in writing, but rather to say that richness will always sustain one more than beauty. If we can collectively push back against the delusion of what a “good life” looks like in media, we will find that a fulfilling one is often as hectic as it is rewarding and that leading with intrinsic purpose will triumph over vanity and self-importance.

For more on the perils of romanticizing one’s life in excess, check out my articles “What Does It Mean to Romanticize?” and “On Feeling Pretty When You Cry.”

Good read, thanks!

I watched Julie & Julia a couple of years ago and it was so emblematic of turn-of-the-millennium optimism about digital culture. If The Devil Wears Prada represents the formalized entry into NYC media-sphere via the right (and brutal) internship, then Julie & Julia represents the internet era fantasy of rising from your anonymous cubicle job into the same media-sphere by the awesomeness of your blog. I never watched Sex and the City so I can't comment much on it, but I don't think one has to have seen it to conclude it, more so than those two movies I mentioned, played a huge role in making a generation want to become writers, especially NYC writers, especially NYC female writers.

On the male side of this equation, have you ever watched Bored To Death? If not, I'd highly recommend it because it's very funny to watch Ted Danson play a clueless 80s relic--a NYC magazine editor who still thinks his collapsing industry can support lunch expense accounts at the Four Seasons--while living in the late 2000s. Instead of gowns and champagne, this NYC writerly fantasy has three-piece suits and Scotch (and weed).

I've often read about how journalism used to be a lower-class profession, whereas now, it's dominated by elite college grads and nepo babies. That, combined with the influences of the fantasies listed above, can't have been good for journalism's image. I write, and am sympathetic to writers, but I too always rolled my eyes when Twitter would explode with circle-jerky elegies and odes whenever some Buzzfeed clone would shut down, as if some Ivy grad's inability to make a good living by penning thinkpieces about Netflix shows was one of the greatest injustices of our society.

Thank you for this. As a former fashion editor, I related to the idea of chasing a dream that was never as glamorous as that depicted in films.