The Perils of the “Photo Dump”

On the Pursuit of Digital Authenticity

I first downloaded Instagram the summer before sixth grade. Charmingly awkward and socially aloof, I probably posted close to ten photos a day for the first few years I had it. I would open up the camera on the Instagram app and snap pictures of the world around me.

Even though I was a child then, still learning social cues, this usage seemed in tandem with how adults in my life were using Instagram as well. Maybe they weren’t posting ten times a day, but the pictures they shared were utterly raw. Grainy, blurry, and sometimes slapped with an aggressive filter. It was a place to more easily share life with family, friends, and acquaintances. A digital version of a family photo album sitting on your grandma’s coffee table. Virtual postcards stuck with magnets on a fingerprint-smudged refrigerator.

Fast forward to roughly 2012 through 2018, rather than a laid-back flipbook of memories, people’s Instagram accounts began mirroring the pages of magazines. Snapshots of casual strolls through parks paralleled the glossy pages of National Geographic. The qualifying criteria for a photo to make it to someone’s account got narrower — not only did the photo have to follow some basic aesthetic conventions, but the photo’s subject had to be something worth looking at.

As a teenager, posting on Instagram went from a spontaneous, daily activity to a heavily planned operation. A new segment emerged during hangouts with friends — “taking pics.” We would scope out attractive backdrops — backyards, suburban sidewalks, and empty parking lots becoming our studios. The photographer would place their thumb on the iPhone camera button and leave it there, rapidly capturing images in succession while the model changed poses. Each image only slightly different from the one taken before it.

My friend would return my phone to me, my photo-ready smile dropping. I would scroll through the captured pictures, searching for ones that were worthy of seeing the light of day. I’m blinking in this one. Acne is visible in that one. Should have found better lighting. Could have sucked in more.

Your Instagram is your personal art gallery and you’re expected to be a choosy curator.

Carefully selecting images that don’t necessarily showcase your best self, but rather the best version of the aesthetic you want to project. The virtual character you strive to stand behind, the digital veil you wish to wear. Scrolling through social media, attending a masquerade ball.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, research has shown that there are relationships between social media and self-esteem, particularly when people engage in social comparison. Rather than the nonchalant snapshots of the early 2010s, users are barraged with a stampede of carefully selected images. Dusted and examined like fossils in a museum, many of these pictures are also passed through editing apps to scrub out any flaws. A highlight reel, a sparkly supercut, of a person’s life. Anxiety can understandably arise.

However, in 2022, a new trend has emerged across social media and the larger appearance economy at large to save the day. A trend epitomized well by the Instagram “photo dump.”

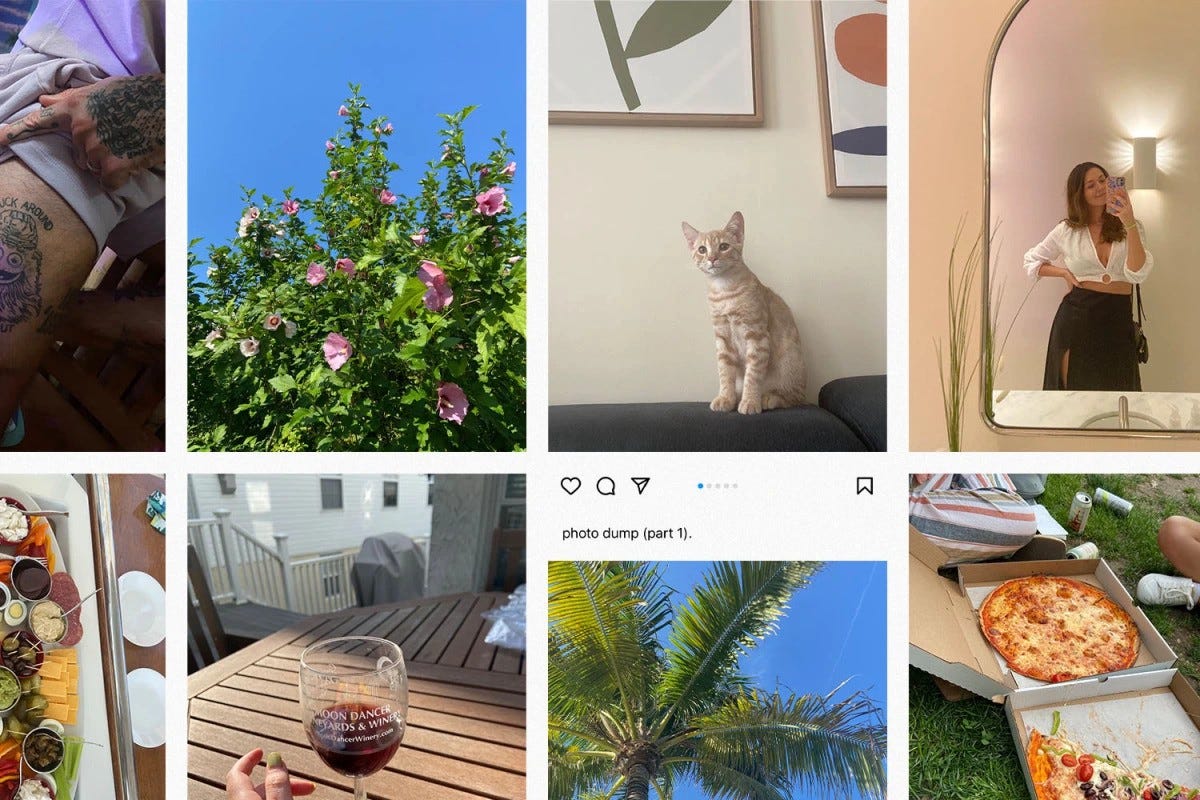

Popular among teenage and young adult users, the photo dump is a hodgepodge of seemingly random and informal photos thrown into a singular Instagram post, often intended as a recap of a month, a semester, or a vacation. A part of a larger cultural movement to “make Instagram casual again,” photo dumps consist of just about anything, but there are some consistent motifs: food and drink, sunsets, a blurry group of friends on a night out, selfies taken with a 0.5 zoom lens, enlarged pictures of road signs with funny or ironic names, mirror selfies of well-styled outfits, maybe a meme, and typically a random attractive photo or two of the user so we remember that they aren’t ugly.

Alongside the photo dump, apps specifically attempting to informalize social media are on the rise. BeReal has seemingly gained a significant younger following, an app that alerts everyone at the same time every day to post a photo of whatever they’re doing at that moment. And as beauty trends waver towards a more natural look (think light-coverage Glossier-core vs. the harsh contours and drawn-on brows of the 2010s), a theme seems to be surfacing — people are tired of having a facade. They want the Internet to feel like a safe neighborhood rather than a high school cafeteria. Or a microscope.

The task of a linebacker and the task of a ballerina aren’t all that different. Either must have endurance, strength, and determination to push through discomfort and pain, whether it’s pushing away powerful offensive players or carrying one’s body weight on the tips of their toes. The one difference is that one is allowed to grunt, sweat, and show their effort. The other must appear easeful. Flawless.

A mask embroidered with rhinestones and a mask woven of grass still hold the same function. To mask.

Instead of just looking attractive online, the goal is now to attempt to look like you’re not trying to look attractive online. Even though you are. The photo dumps of the 2020s appear to echo early Instagram informality when they’re just adding another box to check off on your “posting” criteria. Look good, look like you’re having fun, but not like you know it.

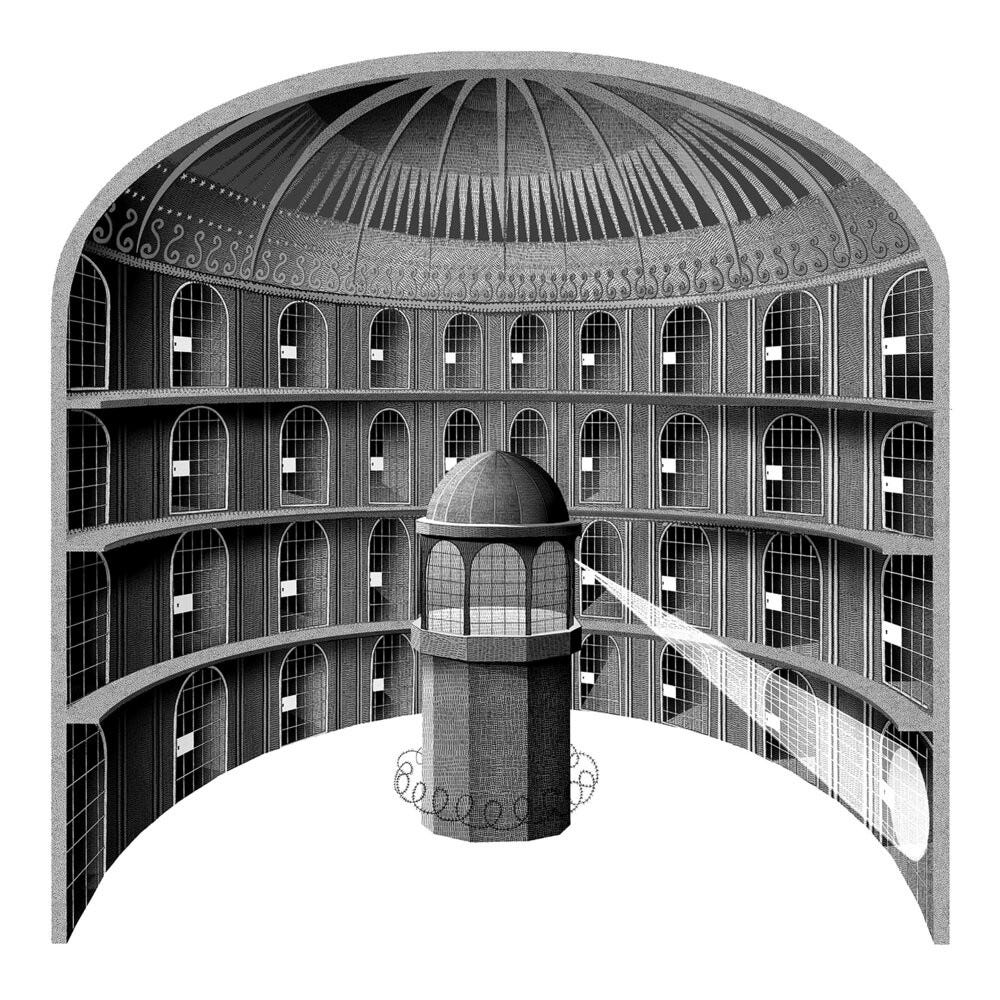

At its bleakest, Instagram likens the panopticon concept developed by philosopher Jeremy Benthem and critiqued in Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975) — a prison that allows a watchman to observe occupants without them knowing whether or not they’re being watched. Users are both the watchman and the occupants, the surveyors and the surveyed. Trying to hold up an attractive, and now effortlessly authentic, front when the light shines on you, making it look like your life always looks this sunny, this carefree. But what happens when the light shines elsewhere?

Is it ever shining elsewhere?

There’s nothing wrong with having a persona per se. In fact, everyone has one to an extent. How we choose to dress or style our hair, whether we put much energy into it or not, projects an image of ourselves into the world. Through our appearance, we teach people how they should perceive us.

Apps like Instagram just offer new layers of perception — the photos we choose to share, how they look together, the filters, the comments, and now how seriously we appear to take “posting pictures” are all meant to encapsulate some message about us. The snapshots in “photo dumps,” as ironically menial and silly as they’re meant to be, are still an attempt to direct the world on how to perceive you. Co-opting “authenticity,” even if it’s hollow, to convey yourself.

There is a satisfaction in feeling like your identity is encapsulated in some way, a small road map of yourself that you can hand people that enter your profile. Like a theater usher offering a program before a play. And having the ability to project an appearance online is empowering in a sense, a way to leave your own archive via digital footprint. Proof of your existence immortalized.

There were times when I felt the need to share everything, that things only happened if they were documented on my social media. There were times when I only felt the need to share the pretty things, making sure all of the pictures on my feed fit some sort of polished aesthetic, turning up the saturation, and plastering on grins.

Today, it’s a bit more intuitive, sharing things when I feel compelled to do so. And yet, I find myself scrolling through my profile, recalling the good times, and also remembering what’s not there.

Glancing up from my phone, I see a group of friends snapping a selfie. In a park. At a restaurant. In the world. Their faces light up when the camera’s on, and smiles drop when it’s off. As they carefully inspect which photos are the most authentic, the most candid, for their July photo dump. Occupants and watchmen. The surveyed and the surveyors.

Perhaps it’s okay if the world can’t completely read me through a set of photos. Maybe it’s alright to keep some slices of life to myself. To prove authenticity to no one.

This is so so so good omg. So inspired by your words

came here after reading your ‘we don’t know how to talk about girls’ piece and i’m just in absolute love with your writing. so good, and am en route to read through more. xx