In the scientific sense, atomization is a process in which matter is reduced to atoms, or small, distinct chemical units. When something becomes atomized, it is converted into a scattering of tiny particles - individual pieces that once equated a greater sum. Though not likely entirely scientifically accurate, this description reminds me of how water beads off into small pearls when a little bit is poured onto a table, small bits detaching from the larger pool.

I’ve heard contemporary thinkers speak of our society becoming increasingly atomized. For a while, I just thought they were referring to loneliness. Sure, people are lonesome, choosing to isolate to cope with the uncertainty of our world, medicated and behind their respective screens, exacerbated by a global pandemic. I’m now realizing that atomization, in the sociological context, doesn’t just refer to loneliness. Rather - like the chemical phenomenon - it indicates a breaking-off of sorts - one mass becomes smaller pieces of mass. Bits of a collective whittling themselves away, like miniature icebergs or Pangea cracking into continents and islands. Once one thing, now many parts.

When bridging the gap between adolescence and adulthood, typically following high school or college, this feeling of atomization is exacerbated for many people. There’s this aggregate that you’re a part of, a machine in which you fit perfectly as a cog, chugging away day by day with your fellow cogs, with whom you learn to identify. And then when you approach the threshold of childhood, the machine is disassembled. Springs and cogs and wires are strewn away from where they were once conjoined. All become minuscule atoms floating respectively.

Writer Willow Liana recalls a friend describing this experience following her college graduation. The friend told Liana:

My first smartphone was a white iPhone 4, sheathed in a white plastic case with hot pink rubber corners that I picked and peeled at when I felt nervous. Upon procuring the device from the local mall with my mom - likely along with an Auntie Anne’s mall pretzel and/or Jamba Juice - I jabbed my sticky fingers on the touch screen, typing my best friend and neighbor’s number into the empty contacts list. I texted her: “Just got my first phone!!!!!” To which she responded “LMFAO! Nice!!” “What’s LMFAO mean??” I responded. She told me what it meant, along with a handful of other texting acronyms to bolster my digital literacy.

I proceeded to correspond with my neighbor, and other school classmates, adding their mobile numbers to my contacts list along with their names and emojis that I thought corresponded with their personalities best (around four emojis per contact). Not too long after that, I also downloaded Instagram, my first social media app, following people I knew from school and the friends and acquaintances of those people, even if I hadn’t ever met them in person.

As its creators likely desired, social media offered a form of connectivity that no other communication technology had afforded previously. Sure, I could talk with my friends anytime I wanted via telephone and even through texting, but social media allowed people to show their friends whatever they wanted to display in a consumable, asynchronous format. It allowed the user to communicate with less energy, as there was no real-time interaction and a much more delayed call-and-response. You didn’t need to directly engage in a dialogue with a person to know what they’re up to. All of this saved energy was necessary for the modern society member, busy with work or school, chores, and other important extracurricular matters.

One day, I knocked on my neighbor’s door, as I had done copious times in the last six or so years. I planned to ask her if she wanted to ride bikes around our neighborhood, glide down the hill, and loop around the cul-de-sac as we liked to do. Upon answering the door this time - and the times that were to come - she told me that she didn’t want to play and wanted to stay inside. When I arrived back at my house, bored and slightly dejected, I flopped on my bed and checked my phone. After some time, I noticed that my neighbor had posted a picture on Instagram, laying in bed with her dog. A bit later she would text me a meme.

As apps like Instagram transition into neo-traditional media platforms - intended to entertain and broadcast but in a less linear fashion - they seem to have an effect that’s more antisocial than social. My friend’s choice to engage with me digitally rather than physically was the start of many pseudo-friendships in my adolescent years. I would meet people at the various places teenagers meet people - driver’s education classes, football games, school dances - and proceed to only know them, from that point on, as digital avatars. Many “friendships” didn’t seem to make it off the screen, once you exchanged Instagram handles and Snapchat usernames, the relationship was initiated. From then on, you could learn everything you wanted to know about the person based on what they shared about themselves on these platforms.

To this day, there are many people that I follow on Instagram that I haven’t said more than a couple of sentences to. Mainly acquaintances from my high school class - I can’t recall what it’s like to make eye contact with them or what their laugh sounds like. But - depending on how much they’re willing to divulge on the platform - I know what their living room interior looks like, where they went for spring break, and what their boyfriend looks like in Christmas pajamas. There’s no reason why I should know any of those things necessarily, this person and I have never had an actual friendship and I likely rarely cross her mind. And yet, I can’t bring myself to unfollow her - social media has made our relationship one-sided and parasocial, but a relationship nonetheless.

This isn’t to say that the internet can’t be a conduit for authentic connection. Plenty of people have been able to craft genuine relationships via social media, often based on fandoms and shared interests and identities. Many of these friendships even leap off the screen, manifesting in offline formats. Others are able to correspond more authentically with people online than with those they know in the “real world.”

Nonetheless, the vast majority of people we encounter online, we interact with in a manner that leans more impersonal. We stare and surmise, consider their presentational choices and then ultimately move on. We more often than not leave people untouched by our virtual study of them. Social media has become, after all, a deeply individual endeavor - we’ve become enthralled with the curation of “self” online, architecting our profiles to be perfect encapsulations of our idealized bodies and minds. I often find myself feeling more concerned with how I appear on social media than how others appear - rewatching my Instagram story periodically throughout the day to get a sense of how it will read to fresh eyes. We’ve been given a bucket of paint and a giant billboard and been told to share ourselves with the world - how could we not become self-absorbed?

To try to connect with people through this highly individualized project, users often lean into its atomized nature. The most common example of this - and what inspired me to write this piece - is the hyper-specific categorization and aestheticization of self that teenage girls perform on platforms like TikTok. In a previous article, I wrote about digital communities that relate over the breezy cotton dress and wicker basket images of the “cottage core” aesthetic, the green juice and yoga mat iconography of “That Girl,” and other aesthetics that have now become old hat. I discussed how this self-aestheticization is a byproduct of living in a world in which the bodies, minds, and lives of girls are romanticized through media. Thus, the way girls know how to view themselves and connect with others best is through developing digestible, highly visual versions of self.

While I think my initial thoughts on aestheticization still hold up, I believe there is something to be said about the ways in which the process bonds online users while still allowing them to cement a deeply individual online presence through categorization. This is clear from the increasingly peculiar aesthetics that girls on TikTok are augmenting, including affiliating with the “vibe” of a food (like the Mediterranean, Aperol Spritz-drinking, Call Me By Your Name energy of a “tomato girl”) or aligning oneself as an “okokok girl” or a “lalala girl,” referring to the ad libs on Tyler, the Creator and Kali Uchis’ 2017 song “See You Again.” In a digital world in which people are encouraged to be highly saturated, singular characters, the only way they can connect is through finding others whose characters bear similarities. Like trying to reverse the atomization process - gluing the broken pieces back together.

In “All the Lonely People: The Atomized Generation,” Liana writes that “the decline of tangible ways to impact our community and the global awareness by mass media has rendered our only routes to unity superficial.” The hyper-aesthetic trends on TikTok remind me of these routes; however, I think the word “symbolic” is more suitable than “superficial.” By declaring yourself an “okokok girl,” you aren’t joining a physical or even richly interactive community - you’re granted a feeling of belonging without having to say anything past “That shirt is so okokok girl-coded.” That sense of community, however, is still present - you feel at one with your fellow Gen Z users through your shared cultural understandings. But there’s only so deep that the community membership can cut when it’s only visual and hyper-singular. For this reason, the feeling of atomization is exacerbated.

I don’t think the answer to reducing atomization is entirely telling young people to simply “touch grass,” a reductive way of urging kids to get off their phones and get outside. Look at what’s outside. There is a collapsed economy, a warming planet, and a late-stage capitalist society that makes it challenging to make a living doing what you love, amid other challenges. Just as past generations have, there is catharsis in consuming media to escape the explicit and subliminal obstacles of the current day. And what past media didn’t afford that social media does is the chance to feel as though you’re part of a greater network, producing and consuming with others in real-time, all in on some inside joke that you can revel in as a collective.

The real issue behind our atomized online communities, the reason why we don’t feel as completely fulfilled scrolling on our phones as we do talking to people in the real world, is because they are intentionally stripped of any real risk. Humans are imperfect, finite beings, and there’s always a chance that one of them will tell you they want to stop being friends or stop returning your phone calls. There’s always a chance that the community you grew up loving will grow a distaste for you and your ideas. Cultivating physical relationships always comes with the risk of losing them. On the other hand, the internet will always be there for you. And when it seems as though you’re no longer connecting with the characters on your For You Page, the algorithm will take notice and spit content that makes your dopamine receptors fire quickly and predictably.

There is risk in crossing the bridge. In telling someone your darkest secrets, in letting them braid your hair or making them dinner or expressing gratitude for their companionship. But I think the deeper reward of human connection is well worth the risk. Where possible, I think we should dare to be bolder in our friendships. Call someone up to tell them you heard a song that made you think of them rather than post a screenshot on your close friends story, hoping they swipe up. Walk down the street and knock on their door, knowing there’s a chance that they won’t answer. Few good things in life come without risk and, accordingly, a machine that makes dopamine fire too easily will eventually sputter and break.

Atoms themselves are quite remarkable - the smallest units of matter. They’re miracle bundles of protons, neutrons, and electrons and without them, we would have nothing. Similarly, when they only exist in their singular form - not connecting to anything - we also more or less have nothing. When atoms join together, however, they make every known thing in our universe. The air we breathe. The chairs we sit on. The stars in the sky.

For a similar article on the need to connect offline, check out my article “Who Are We Without the Internet?”

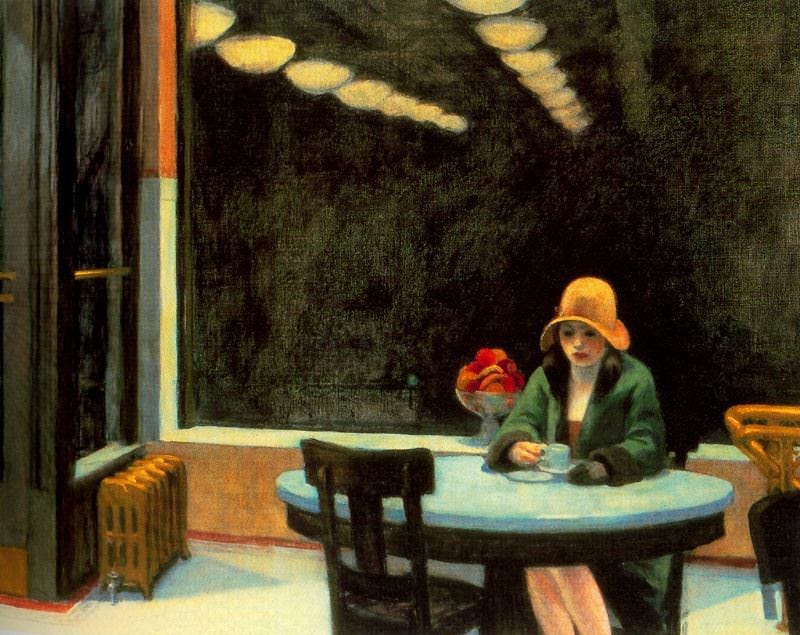

also wrote this great piece on loneliness which definitely inspired my using an Edward Hopper painting for the cover.

I relate so much to your statement about our profiles being "perfect encapsulations of idealized bodies". When social media with snapchat, instagram and tumblr were new and I myself a whole lot younger, I thought it was great to connect with people. I as well tried to be someone I wasn't but realized early on that I don't get that much joy of it like friends of mine back then. I tried to fit into a certain niche that was based on a fluctuating trend. If that means posting pictures with dog face filters or highly edited pictures off of picsart, retrica etc. then sure, why not? I seeked for validation, acceptance and belonging. For my special niche or trend which I then found in things like book girl, vinyl girl or arctic monkeys girl.

But in the last time I needed to take more and more breaks off of social media as it was keeping me from the "real" world, from real friendships - and in particular from the real me. What was once shaping my own unique personality was now destroying it with trends changing quicker than my eyes can blink.

Have you read this? related to your article, you'll like this one, "The big idea: why relationships are the key to existence" https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/sep/05/the-big-idea-why-relationships-are-the-key-to-existence