In Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory (1988), theorist Judith Butler posits that gender does not exist innately in the human body. Rather, gender is constituted by the repetitive, unconscious acts humans in modern society perform every day to convey their gender identity to the world around them. In a simplified sense, when modern cisgender women unconsciously wake up, do their skincare routine, apply make-up, and don themselves in “feminine” clothing before stepping onto the street, they are performing gender. Cisgender men similarly perform their gender when they select a “masculine”-signaling outfit and speak unconsciously with a lowered voice. Even non-binary folks perform their gender identity by performing acts that are subversive to the gender binary - defining themselves in opposition to it by not ascribing to it in their performance. Gender is thus not an individual conception but one that is established through both these repetitive, unconscious acts as well as social sanctions. Gender isn’t something one has - it’s something one does. Performs.

Drawing parallels to Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), Butler’s work is some of the first to define “performance” in this sociological context. Since 1988 and the advent of social media in the twenty-first century, “performance” and “performativity” have been used in varying contexts. Today, if a person describes another person as being “performative,” most others can deduce that they’re referring to someone behaving in a way that is merely for optics. “PR relationships” are a great example of this: two famous people appearing in public together so that the plebeians view them in a certain way. Celebrity philanthropy and corporate social responsibility are other realms people often deem “performative,” as it’s assumed that the people and corporations involved are more concerned with the profitable appearance of the act rather than the outcome of the act itself.

As of late, “performativity” has been used in reference to different forms of activism. Specifically, what many refer to as “slacktivism,” or the practice of supporting a social or political cause through means that require little effort or commitment, such as signing a petition or sharing a social media post. Since the 1990s, slacktivism has been critiqued and defended. Many argue that this form of advocacy is too low a commitment to be meaningful, allowing people to feel a burst of altruistic satisfaction without creating concrete, actionable change. Others defend the phenomenon under the pretext of raising awareness, also stressing that engaging in this lower-effort activism can be a gateway to more involved organizing efforts like protesting and donating.

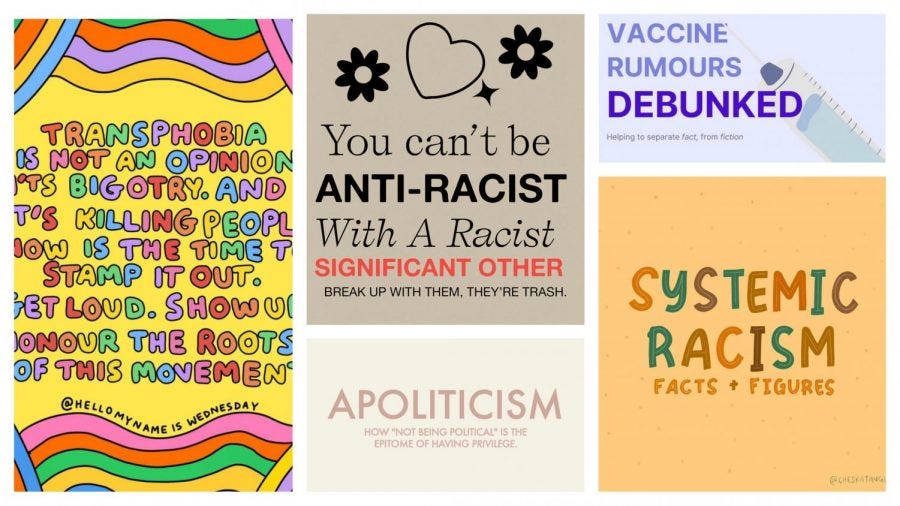

While slacktivism and “performative” activism have been subjects of discussion in academic and activist circles for decades, the conversation further erupted in mainstream discourse after the advent of the organization Black Lives Matter following the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer in 2013. Particularly after police officers murdered George Floyd in 2020, social media erupted with the sharing and re-sharing of pastel infographics breaking down systemic racism and the prison industrial complex. But after just a few months of reposting and educating, social media feeds went back to business as usual, igniting discussion about whether “raising awareness” online merely sets an expiration date on a cause. Be it the lightning-fast news cycle or the speed at which social media discourse rotates, it seems as though even national and international tragedy is often reduced to a trend in the modern age.

Further, what’s fascinating to me is the fact that social media activism has created a prescription of sorts for how to signal morals to others online. Author Latham Thomas coined the phrase “optical allyship” in her book Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor (2018). Similar to PR relationships, optical allyship can be thought of as solidarity and hollow statements that are made for mere appearances, not adequately addressing the root causes of issues.

Most recently, I’ve seen an adapted form of this play out in a way that might be better described as “optical morality.” There’s a certain song-and-dance of morality that people perform online to put themselves in closer proximity to “good” internet ethics, whether they actually abide by them or not. Words and ideas are co-opted from various intellectual disciplines. People are expected to have the “right” take on whatever Twitter’s discourse of the day is, which is often a blasé pop culture topic like Adam Levine’s infidelity or one of Buzzfeed’s “Try Guys” cheating. Those that neglect to adopt that language and those takes are shunned on the first try.

Most recently - and what inspired me to write about this topic - popular internet personality @best.dressed became the vehicle for optical morality after she came under fire for romanticizing smoking in an Instagram photo of her lighting up. Of course, it’s well-known that smoking can be hazardous to one’s health. But aside from the “good” or “bad’ nature of smoking itself, the knee-jerk reactions to @best.dressed reflect a larger phenomenon of condemning people who aren’t “doing the internet” correctly. A similar collective reaction was ignited online when TikTok personality Serena Shahidi (or @glamdemon2004) posted a video jokingly urging people to not use their appearance as their sole source of confidence (the post was later deemed classist).

In the age of “cancel culture,” the fear of being penalized by the internet often appears to be a stronger motivator for good behavior than actually imparting good change. If you know how to do the song and dance to signal your morality online - if you know which takes and terms the internet deems appropriate that week - you can be left unscathed. How effective is a world in which we must know how to behave to avoid punishment - a virtual tar and feathering in the Twitter-sphere public square - but don’t need to know how to behave to transform people and systems for the better? What might it look like to adopt a framework that facilitates conversation and rehabilitation before immediate disposal?

This framework is one that is already being imagined and adopted by brilliant abolitionists and thinkers like Adrienne Maree Brown. In her blog post “unthinkable thoughts: call out culture in the age of covid-19,” Brown argues that the current groundwork for online activism is punitive in nature. Much like the American police system, we as a culture have an obsession with punishing the “villain,” even if it means overlooking the act of supporting and nurturing survivors. Brown illustrates this point more eloquently than me here:

“the master’s tools feel good to use, groove in the hand easily from repeated use and training. but they are often blunt and senseless…the additional truth is, even though we want to help the survivor, we love obsessing over and punishing ‘villains.’ we end up putting more of our collective attention on punishing those accused of causing harm than supporting and centering the healing of survivors.”

Brown makes it clear that she doesn’t find call-outs to be entirely wrong, they have a time and place. Rather, in many cases, she doesn’t find it transformative to call people out for instant consequences without attempting to mediate or set boundaries, as it denies people complexity and the capacity to grow.

The internet is an odd vessel, emulating a void for people to shout the unthinkable into. It’s also, in other cases, a prism that can allow certain sentiments to be misconstrued. As with many of the internet-related topics I write about here, navigating call-out culture online is a complex and contextual idea. In the context of our real lives, I feel like people are becoming increasingly comfortable calling out people they trust in a compassionate way and setting boundaries when appropriate if and when those people don’t comply. Particularly for people with privileged identities, making the effort to educate harm-doers can go a long way.

I’m certainly guilty of avoiding the transformative approach in my own relationships. I’ve been quick to write off the people in my own life that have hurt me - either through ghosting, gossiping, or excommunicating. None of this is to say that distance shouldn’t be created between ourselves and harm-doers, especially after attempts at rehabilitation have failed time and time again. We’re only human and we need to protect ourselves - picking our challenges wisely to protect our peace and livelihood. At the end of the day, and as Brown alludes to, it’s more important to prioritize caring for the hurt than to dispose of the one causing harm. If we don’t take care of ourselves, we can’t expect to help others grow too.

At the same time, allowing people the opportunity to show us their progress - if they’re committed to the process of growth - can be a radical act. If we begin to view ourselves and our loved ones as having the capacity to transform, we can start to further realize a world in which wrong-doers and dinosaur institutions have that same capacity.

For more on transformative justice, I highly recommend checking out We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative Justice (2020) by Adrienne Maree Brown. Click here to explore more of her work.

This is great!! I'm definitely going to check out "We Will Not Cancel Us." I love the point you made here - "At the same time, allowing people the opportunity to show us their progress - if they’re committed to the process of growth - can be a radical act."

love the essay! i just recently read “we will not cancel us” and it was so good