Let’s (Not) Talk About Sex, Baby

“Puriteens,” Gen Z Conservatism, and Not Reading Between the Lines

On March 2, to the surprise of many, Anora (2024) was the big winner at the 97th Annual Academy Awards, taking home the trophies for Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Film Editing. Director Sean Baker matched the record set by Walt Disney for the most Academy Awards won by one person in a single year, and Anora (2024) became the fourth film to win both the Oscar for Best Picture and the Palme d’Or, the highest award at the Cannes Film Festival.

This sweep was surprising for different reasons to different people. For one, the film won zero Golden Globes and SAG Awards, the winners of which typically fall in line with the Academy Award winners. Anora was an independent film produced and distributed by Neon. It had a forty-person crew and a $6 million budget (though it did spend around $18 million on marketing). As such, many argued that it didn’t have the “feel” of an Oscar-winning movie. No big-name actors or grandiose sets. It wasn’t a period piece or a biopic or a screenplay adapted from a coveted novel. It also centered the fresh-faced Mikey Madison, a twenty-six-year-old starring in her first lead role in a major motion picture. Madison is the first member of Gen Z to win an Oscar, and it couldn’t feel more ironic that she won it portraying a sex worker.

Incidentally, Anora stirred up much online conversation about sex scenes, specifically Madison admitting to not using an intimacy coordinator on set. Some critics spoke at length about the lack of interiority Madison’s character had in the film - how we didn’t get to know enough about her particular desires and motives outside of her material ones - and how the film relies on regressive stereotypes of sex workers as “crass, impulsive, and pathologically sexual.”

I found all this criticism quite interesting because I don’t find Anora to be a particularly erotic film, despite it depicting a protagonist that engages in a lot of sex. Any time sex is shown or referenced, it serves a narrative end. Anora’s scenes in the strip club are brief, as are her sex scenes with Vanya, which are more comical than they are sexy. Sex is conceived quite practically - a service that Anora performs in exchange for money. The lines between customer and merchant blur when the couple becomes more playful and romantic. As long as sex is at the center, their relationship remains transactional.

How does a generation that grew up online consider sex - an act that requires a level of physical and emotional visibility that online interaction can often curb? How does one factor in the fact that this generation also came of age, in part, during a global pandemic, a time of touch deprivation? On the surface, one might assume that Gen Z would be wary of engaging in sex and with “sexual” media - and they would be somewhat right. Studies show that today’s young people are pushing off their “firsts,” waiting longer to drink alcohol, acquire a driver’s license, get their first job, go on their first date, and, indeed, have sex for the first time. A certain sect of online zoomers, referred to as the “puriteens,” are incensed by displays of sexuality on small and big screens alike. For Rolling Stone, EJ Dickson argues that the group may represent a loud minority of zoomers who grew up “negotiating murky spaces of the internet” and, thus, perhaps a group with a “stronger understanding of sex and the dangers of sexual exploitation more than any other generation.”

While Gen Z may have a firmer grasp on the language surrounding exploitation than past generations, there are many instances of them collapsing the concept with sexuality more generally in online discussions. There’s no better demonstration of this than recent criticism surrounding Sabrina Carpenter’s performance of sexuality.

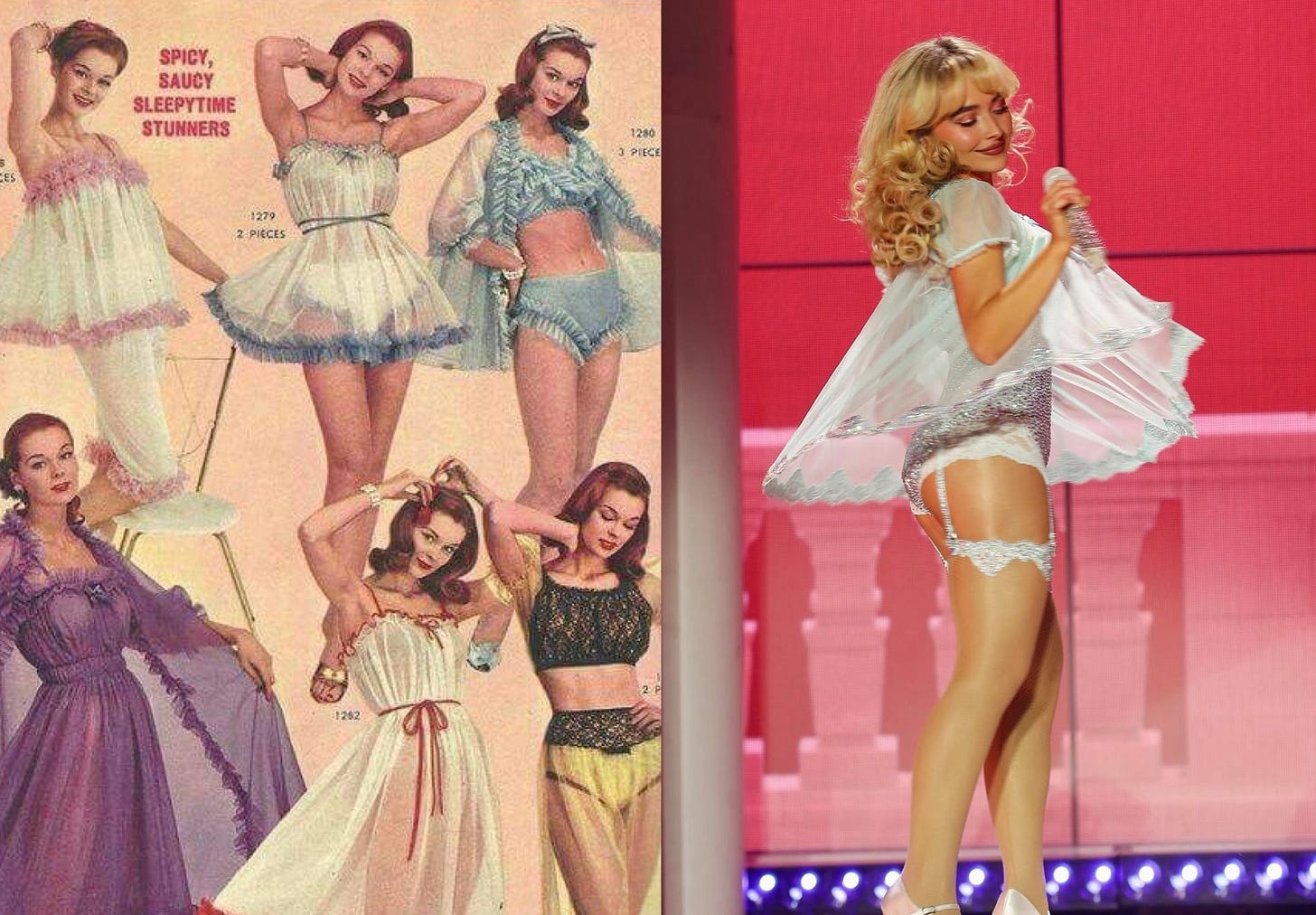

In September 2024, Jade Hurley’s viral essay “your fave is selling a pedophilic fantasy” posited that Carpenter’s lyrics and visual aesthetic rely on “a ‘90s-era, hyper-sexualized girlhood,” which offers audiences the “choice of a pedophilic fantasy.” Hurley specifically referenced Carpenter’s Skims’ campaign, in which she emulates a teenage girl draped across her bedroom in lingerie, as well as a fairly obvious Lolita reference in her photo spread for W. On her Short n’ Sweet album tour, Carpenter also plays into the innuendos strewn across her songs, simulating different sex positions for each city during the cheeky lyrics on the second verse of “Juno.” “Have you ever tried this one?” she sings while arching her back towards the crowd or launching into a split. Media outlets have been quick to criticize Carpenter’s overly sexual performance of this song, particularly after she simulated oral sex at a Los Angeles tour stop. Her babydoll dresses, glittery pink set design, and history as a Disney Channel star may be fooling parents into thinking she’s a family-friendly artist. She’s in fact a 25-year-old pop star singing songs about being a young modern woman - which means singing about sex and romance, at times. “I’m 17 and AFRAID of Sabrina Carpenter,” one Twitter user cried out in response to the madness.

I appreciate Hurley’s argument. And I also appreciate Final Girl Digital’s “rebuttal,” “Who’s Afraid of Sabrina Carpenter?” which highlights Carpenter’s myriad of nostalgic references, outside of the one Skims campaign and odd Lolita photo. Carpenter’s visual library references American and New Wave French icons from the ‘60s through the ‘90s, such as Brigitte Bardot, Goldie Hawn, and The Nanny’s Fran Fine. The other photos accompanying Carpenter’s infamous W spread were quite womanly, featuring her shot from the waist up in blazers. I attended the Brooklyn Short n’ Sweet tour stop, and the tone of the show was quite mature from top to bottom, centering Carpenter as the young woman star of a Mary Tyler Moore-eque sitcom, involving background dancers posing as friends stopping by her playhouse to take shots and party. The babydoll dresses are more of a callback to 1960s fashion than an attempt to look like a child. I’d guess Carpenter’s short stature would have more to do with the controversy than anything else.

Similar to Anora’s storyline, discourse about Carpenter’s sexuality also often ignores the humor woven throughout her songwriting and performance style - her lyrics are often pun-ridden and delivered in a tongue-in-cheek style. This inability to parse sex and sexuality from objectification is what’s underscoring young people’s recent discussions surrounding the topic online, resulting in all mentions of sex often collapsing under one clumsily defined umbrella.

At least in the United States, it’s clear why this might be occurring. In addition to the integration of pop psychology and pop activism terms in everyday zoomer-speak, more generally, there is a sex education crisis in this country. For a nation that’s as comfortable as we are putting sex - specifically, sexualized women - onscreen, we are quite uncomfortable talking about it in a more practical sense. Only 39 U.S. states have government-mandated sex education, and the content of those programs varies tremendously. While 37 states require abstinence to be taught, only 18 require information about birth control. 26 require that sex and HIV education is “medically accurate,” a phrase that can be misconstrued innumerably. Perhaps the most startling figure, only 12 states require sex education or HIV/STI instruction to include information about consent.

America is also having a literacy crisis, which won’t be aided by Trump’s plans to close the Department of Education. Young people are less able than ever to comprehend complex stories across film, music, and literature, favoring storylines with clear-cut endings and obvious throughlines. When your media is devoid of any underlining meaning, sex scenes are truly just sex scenes, stripping them of any symbolic or anecdotal purpose, which may make them seem gratuitous.

In her video essay “is hollywood finally sexy again?”, Mina Le talks through the legacy of film censorship in America and how the “Hays Code” dissolved as puritanical public opinion began to shift following World War II. Still, the U.S. film rating system differs from that of other countries, typically rating sex in films more harshly than violence, whereas most everywhere else has it flipped. The U.S. rating system also doesn’t take the context of sex scenes into account - blanketing consensual sex and coerced sex under the same description of “sex” onscreen. Le highlights that under American rating systems, TV shows like HBO’s Euphora and Netflix’s Sex Education are rated the same, despite the former containing explicit depictions and references of statutory rape and sexual violence and the latter being a more earnest, humorous depiction of sexual exploration as an awkward teenager.

Le suggests that instinctually, young people might associate sex with degradation because of how women have historically been objectified onscreen. For decades, women who were sexual onscreen weren’t women who were confident and secure in their personhood. Their personalities and physical compositions were written and performed for the pleasure of male characters and male viewers alike. As such, I can understand how a less literate group of media consumers might fail to perceive the nuance inherent in intimate scenes in contemporary cinema.

In truth, the sexiest films are often devoid of sex - pumping up the eroticism inherent in emotional tension, physical proximity, and quiet yearning. Luca Guadagnino’s 2024 film Challengers accomplished sexiness without even writing in a sex scene, whereas films like Poor Things (2023), Nosferatu (2024), and Anora (2024) allowed sex to be the stand-in for self-discovery, repression, and transactions of power.

While the “puriteens” are a quite niche and quite online minority of media consumers, declining literacy rates and American conservatism threaten nuance across media of all forms. When we cannot find deeper meaning in film, music, and literature, our ability to detect nuance across our day-to-day lives and geopolitical matters will similarly erode. Needing to be spoon-fed the answers - via BookTok, via cut-and-dry plotlines, via painful transparency - allows for the spoon to be potentially wielded by an agent with malintent. Those unable to understand symbolism are destined to ignore the signs - particularly signs of power and signs of fascism. Being able to parse out difference across homogeneity, search for the grey areas, and even develop a unique point of view will continue to be assets in a political and cultural landscape that wants to tell you what to think.

This is one of the most precise breakdowns I’ve read about the collapse between sex and sexualization, especially as it's playing out across Gen Z discourse. The literacy crisis angle was sharp—how lack of media comprehension flattens everything into moral panic.

Also really appreciated the reminder that sensuality doesn’t require skin—it requires tension. “The sexiest films are often devoid of sex” might be the most subversive sentence of the piece.

Saved this one. Will be thinking about the spoon metaphor for days.

Loved that conclusion. Very poignant and well written!