Jogging in the Suburbs

Absence, Presence, & Containment

One of the great joys of being an eldest sibling is showing your younger siblings media they’ve never seen before. There are the classic moments of celebration in life: graduations, weddings, births, and so on. But there’s also showing your sisters the Twilight franchise for the first time during deep COVID, the whole room erupting in screams during the twist in Breaking Dawn - Part 2. There’s also playing Lorde’s Melodrama for them in the car on a road trip when they’re on the crest of fourteen and sixteen years old, no one speaking a word until “Perfect Places” concludes. Showing them books, movies, and music that resonated with me at their age and watching them take to them with the same fervor is a unique joy that only an older sibling is afforded. I still maintain some influence over them, and there’s enough distance from my beloved media that it’s nostalgic without seeming antiquated. By the time I have children, they’ll probably learn how to make movies five-dimensional; all that I loved will be archaic.

You can imagine my stupid joy when they told me they’d never seen the Jurassic World franchise before. This revelation unlocked something in me: I remembered that I had developed a quite random obsession with Jurassic World in June 2015. Going to the movies is one of the few autonomous summer activities a fifteen-year-old can engage in after getting dropped off at the mall by her parents for the day. In the summer of 2015, I remember watching Jurassic World three and a half times in theaters with three different configurations of friends.

I watched the movie again with my sisters when I visited home last, and cinephiles be damned, the Jurassic Park reboot didn’t disappoint any of us. Similar to my last couple of Star Wars rewatches, I’m beginning to realize - quite baldly - that resonant subtext is what separates a decent summer blockbuster from a fantastic one. Across old and new episodes, Star Wars’ telling and retelling of the rise and fall of fascism - “good” and “evil” not necessarily disappearing, but taking different forms, and at times, being different sides of the same coin - remains fresh and more relevant than ever in 2025.

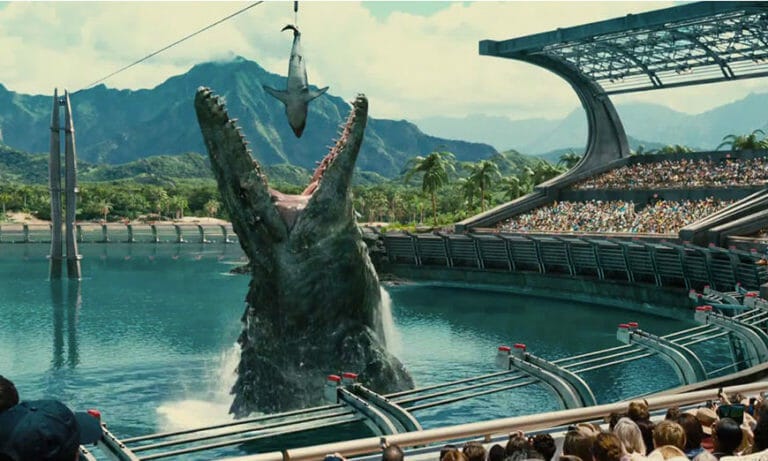

The Jurassic Park films illustrate what happens when intelligent, powerful life is exploited for capital gain. What happens when we attempt to confine a being, alienating it from its natural circumstances? What happens when man assumes mastery over the natural world? The answers are quite grisly. Outside of the movies, we can find the effects of containment in many places; the obvious one being SeaWorld and Tilikum, the orca whale that killed three people during his thirty-three years in captivity. There are many more subtle examples, though, much closer to home.

On my last visit home to Washington, I decided to go on a run in the suburbs, which I had never done before. For some reason, I usually tend to favor the reliability and privacy of our home treadmill. But it was a beautiful summer day, and I’ve grown accustomed to the fresh air and freeing feeling of running outside in the city, so I figured, why not?

I asked my sister, who’s home from college, where she prefers to run in the neighborhood, and she told me to the dog park and back. The route is a straight shot on a paved, tree-lined sidewalk, perfumed with the scents of cherry blossoms and dotted with “little free library” boxes. But runners on the path are weirdly scarce, unlike the usual bustling route I jog along through Fort Mason in San Francisco. But more space is always welcome. Who doesn’t want more space?

I slid on my shorts, laced up my shoes, and took off. It was a warm day, around eighty degrees Fahrenheit, so I broke into a welcome sweat soon after starting. What struck me first was the quiet. I don’t listen to music when I run in the city - I don’t usually need to. The sounds of foot traffic, cars, and the bay lapping on the shore of Aquatic Park make for a satisfying soundtrack - adding music into the mix would be too much stimulation. But in the suburbs, the quiet is like a knife; it’s altogether peaceful and eerie, punctuated with the sounds of birdsong and distant car engines.

As I ran, I came across a middle-aged woman clad in athleisure, power walking while she listened to an audiobook aloud, an iPhone held up to her ear. To pass without startling her, I diverted my path onto the grass median separating the sidewalk from the street, arcing around her in a neat rainbow. Despite giving her over an arm’s length of space, she startled, gasping and jumping as I ran past. Another person crossing her path, especially so briskly, was unexpected. I gave her a little smile and wave as I ran by, stressing that I came in peace.

I carried on, gaze fixed ahead, feet hitting the pavement, focused on breathing evenly. As I ran, the occasional car slowed as it passed me, eventually matching my pace. I glanced at the driver’s seat of each of those cars, expecting them to contain one of my neighbors trying to say hello. But to my surprise, it was always a stranger. As soon as I looked their way, they whipped their head back to the road and sped back up with little hesitation.

Despite the absence of eyes on the road, I felt as though I was being watched. I avoided glancing at the woods across from the neighborhood or at the windows of the houses lining the sidewalk in the off chance that two yellow glowing eyes would meet mine. After completing my three miles, my pace dropped to a walk. As I cooled off, I noticed a small vegetable garden in the corner of someone’s front yard, overflowing with zucchini blossoms and contained by a small white fence. I stopped in front of the lawn to take a look, breathing heavily, sun bouncing off the gardens’ shiny green leaves. My gaze rose to the window of the house, where a cream curtain had been pulled back, yellow glowing eyes piercing mine, eyebrows furrowed. I quickly walked away.

Eliza McLamb's newsletter introduced me to the work of Mark Fisher, specifically his definition of “eeriness.” Fisher describes eeriness as a failure of absence or presence; either something being present that isn’t supposed to be, or nothing being present when there should be something. Suburban life teeters between being overly present and overly absent. Suburbs were designed for neither abundance nor emptiness. On the one hand, they’re the sites of countless Fourth of July barbecues and pumpkin carving contests. They’re places where kids are free to ride their bikes around cul-de-sacs and play Capture the Flag until dusk, filling the silence with their screams. On the other hand, the squares of private property are often so large, relative to multi-family housing in a city, that it can feel like each party is residing in their own kingdom, their fenced yard a dragon-guarded moat, safeguarding their goods.

Suburban containment offers the illusion of safety by placing space between people, their families, and entities that threaten their sanctity. However, these built environments lack the comforting bustle of a city, which offers, at times, a noisy reminder of humanity. They also lack the sublime and beautiful qualities of rural America, which draw attention to our humanness by making us feel small, drawing contrasts between our bodies and the scale of the land, the world, we live in.

Contemporary suburbs fall somewhere between the city and the country. Suburbs can sprawl, containing, at times, thousands of people. But these people are all contained within their dwellings, privately owned dwellings upon which ownership is made clear via a neatly trimmed hedge or a wooden fence. When you draw a line - a barrier - you become all too aware of those who have trespassed it, and all too paranoid about those who will encroach on it in the future. Hence, the proliferation of surveillance devices, such as Ring cameras, as well as the yellow glowing eyes boring holes into triple-pane glass, veins popping out of their foreheads.

Growing up, I was certain that we lived in the woods. My backyard spilled into a densely packed forest, furnished with vibrant moss, native trees, and a single Redwood cedar. I’d venture back there with the neighborhood kids on occasion until we came across coyote droppings, which sent us comically sprinting in the opposite direction. On the fifteen-minute drive up to my house from the 405, one came across numerous housing developments, but also several independent farms. I would ogle at the ponies, alpacas, and goats that roamed on their respective plots of land, my tiny hand reaching out to them from the car window.

None of those farms remain now - they’ve been mowed down and replaced with identical craftsman houses. These newer homes possess large footprints but tiny yards - the houses themselves nearly extend to the property line. This is all an attempt to maximize land use, cram as many homes as possible into a plot to house the influx of families moving to the greater Seattle area for work.

I find myself getting upset about the “changes” in my home neighborhood until I remember that my family was once the cause of similar changes. Our house didn’t materialize spontaneously - there were once trees there. There was once a family, or at least a person, who watched the forest down the street from them get leveled. Who watched the land get divided and disseminated like sugar cookie dough. I can’t stare too hard at these new developments, lest I become another set of yellow glowing eyes, aloof to my hostility.

Suburbs are the perfect realization of so many American virtues. Breaking ground and then getting rattled when someone breaks ground beside you. How earth-shattering the smallest changes are when your environment is never-changing for decades? Suburbs are a centuries-old concept, but are quite compatible with many frictionless inventions of the modern era. Like those affluent enough to afford Ozempic, daily DoorDash, and the like - products and services that make eating and maintaining one’s body an effortless and numbing endeavor - those well-off enough to live in a suburb are granted the privilege of rarely chafing against those in a different class than them. There is no hand less resistant to friction than a smooth one, than one that’s chipped away its callouses.

I’m told that the city can’t mow down the forest behind our house because a rare owl lives there, as well as a stream, making the land too marshy for a home foundation. I’m glad because looking into someone’s house from my house would make me all too aware of the boundaries, of the containment. Like a meditating mind getting angry when its thoughts wander off, there’s no more surefire way to go insane than to avoid insanity.

I feel this whenever I travel from my walkable city to visit family on Long Island... no sidewalks anywhere, and when I go for a walk (along the street gutters, basically) the way the residents stare at me from their front yards, it’s as if I’m navigating my way down the street by canoe.

This made me think of this essay in New Inquiry on the culture of neighbors…I think it would resonate with you! https://thenewinquiry.com/new-neighbor-whos-this/