Regina George. Sharpay Evans. Blair Waldorf.

If you’re a young girl or woman within spitting distance of the millennial or Gen Z time frame, chances are those names mean something to you.

Regina, Sharpay, and Blair are just a few examples of what can easily be dubbed the “Mean Girl” trope, popularized in romantic comedies of the 1990s and 2000s. Mean Girl is almost always white and rich, dreamily drifting into school in a convertible sports car that her parents gifted her for her Sweet Sixteen. She’s often followed by an entourage of sorts: a group of fussy, doe-eyed wannabees, a golden athlete boyfriend, and sometimes a group of adoring devotees. Mean Girl is also importantly, fittingly, and positively evil - she bullies relentlessly, often plotting schemes with her aspiring minions to prevent others from overthrowing her regime.

The Mean Girl recipe of the 90s and aughts has been perfected through countless iterations. But throughout the innumerable variants of Mean Girls, one characteristic is a constant.

Mean Girl is always hyper-feminine.

She embodies feminine stereotypes on steroids - immaculate faces of ultra-glamorous makeup, Victoria’s Secret push-up bras, bedazzled notebooks, luscious waterfalls of thick hair, manicured nails, and an undying obsession with fashion. Mean Girls of the 90s and early 2000s look like they got caught in a Claire’s thunderstorm followed by a Limited Too tornado.

But to fully understand the gravity of Mean Girl, one has to get acquainted with her nemesis: the girl who’s Not Like Most Girls.

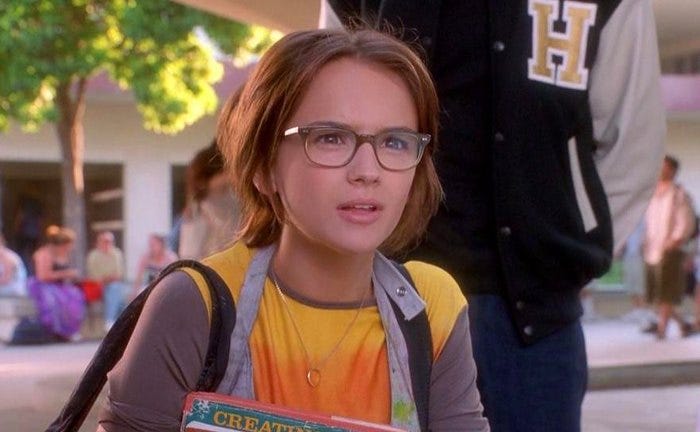

Not Like Most Girls is the protagonist in our story. Think Cady Heron in Mean Girls (2004), Gabriella Montez in High School Musical (2006), Laney Boggs in She’s All That (1999), the list goes on. Unlike Mean Girl, she is pleasant and shows compassion to friends and strangers alike. She is often smart or talented in some secretive way, perhaps notably bookish, artistic, or athletic. When one of these hidden talents is uncovered, she piques the interest of another prominent character, typically the attractive boyfriend of Mean Girl.

Strikingly, Not Like Most Girls’ defining, stable trait is the complete opposite of Mean Girl’s: she is decidedly not feminine. She either subtly dresses more plain and boyish than Mean Girl - more pants, less pink - or downright rejects fashion and makeup altogether, deeming it unnecessary or trivial. Her hair is either thrown up in a practical ponytail or stuffed in a knotted bundle atop her scalp. Rather than holding a handbag, she can be found roaming the hallways with her nose stuck in a book, clumsily bumping into fellow students.

Audiences are made to root for Not Like Most Girls, in part, because she’s the character most can relate to. She doesn’t have the luxurious resources Mean Girl has, she’s identifiably awkward, and, most importantly, she’s nice. An undeniably solid role model.

Based on their unique identity traits, lived experiences, and social locations, people bring different perspectives to the work that they produce. Just as you would expect members of different political parties to define the word “freedom” a little differently, you wouldn’t expect a Holocaust survivor and a six-year-old girl to produce the exact same product when asked to draw a picture of the word “hope.” Different beliefs and backgrounds breed different outputs. Incidentally, artists imbue their ideologies and values into the art they make deliberately and subconsciously.

The cookie-cutter characterization of a hyper-feminine Mean Girl and an un-feminine protagonist is not an accident. There is a reason why this formula has thrived for decades. The same reason why young boys are reprimanded for preferring to play with dolls and wear skirts while young girls are more often praised for not being afraid to “get dirty” playing in the mud and stuck with the label “tomboy.”

In a patriarchal society, femininity is viewed, at best, as a cute deficiency, and at worst, as evil.

Obviously, America has moved past witch trials, yet the disdain for femininity persists in slighter ways - less boisterous but loud enough to permeate the consciousness of media consumers of all genders. For years, teen rom-coms have disseminated the message that if girls want to be viewed as intelligent, interesting, and, in the end, worthy of an equally smart and steady boyfriend, they ultimately need to abandon their overly-feminine qualities. Eliminate your vocal fry. Wipe off the lip gloss. Prove that you’re the exception, the brilliant needle in a haystack of ditzy girlishness, to be seen as having any kind of substance. Prove you’re not like most girls to prove your significance.

And somehow, the pendulum manages to swing to the other extreme too, conceiving a swarm of opposing, but related identity issues. If girls don’t conventionally groom or adorn themselves like the stereotypical woman - if they abandon makeup, long hair, and dresses - they are often seen as less of a girl. Sometimes they’re asked if they are even girls at all, as conceptions of gender are inextricably tied up with appearances.

And so a balancing act fit for the circus emerges. Girls quickly learn to be tightrope walkers, walking the fine line between being a socially acceptable, conventionally attractive woman, but not being so girlish that they’re seen as stupid, unserious, or catty. Perhaps also while trying to figure out the person they want to be for themselves, apart from the media influence. If that’s even possible to discern.

The stress of this balancing act bolsters an already thriving culture of competition among women. When the patriarchy only allows a small, fixed number of pedestals of power for women, they must fight each other for them, leading to a flourishing cesspool of internalized misogyny. Rather than targeting this energy towards dismantling the patriarchy - the source of this issue - girls express hatred toward other girls, their designated opponents. And instead of using some of this energy to uplift other girls, they direct it towards trying to be the exception to secure a spot on the prized pedestal, be it a gateway to a higher paying job, a boyfriend, or just healthy self-worth.

I’ve personally sympathized with either character throughout my life. I’ve been the sparkly pop-obsessed, skirt-clad fashion lover, the edgier, moodier, intellectual, and places in between. As with many girls, I’ve gotten ensnared in the trap of internalized misogyny time and time again. I’ve loudly hated music and movies heavily marketed towards girls, thinking it would get me some extra brownie points from boys I was crushing on. I’ve rolled my eyes at girls being unapologetically themselves in high school, jealous of their confidence. I thought doing all this would somehow get me more social capital, when all it got me was a confusing, ever-spiraling sense of self. To love femininity or to hate femininity. A dog chasing its tail to infinity.

Fortunately, in many ways, life continues to imitate this type of art less and less as people work tirelessly to dismantle oppression embedded in a myriad of social spaces. In the real world, women are showing us that there are infinite ways to be a woman. That there should be enough space for people of all backgrounds to thrive in society. Real women are pushing back on systemic boundaries, showing others that you shouldn’t have to look a certain way to walk into certain rooms or talk a certain way to get people in power to listen to you. We certainly aren’t living in a world that’s somehow “fixed” misogyny. Still, it’s exciting to celebrate the artists, scientists, athletes, and activists emerging and excelling with every identity under the sun.

Today, I’ve gotten more and more comfortable with the fact that I can be conventionally intelligent and feminine. I can enjoy reading complex literature and scream pop music at the top of my lungs right afterward. My watch history can waver between documentaries and romantic comedies. Multiplicities can exist in me and every girl. Every person.

Girls - both the nice ones and the mean ones - have the capacity to exist in an assortment of packages. A rainbow of hues.

Just read this, Madison. Very tricky unpacking here. I have several memories and thoughts right now from high school to academia. As someone who clearly was Not The Mean Girl and only felt an interest in flashy lipsticks in her early 20s, I still grapple with the confusion of how much of the accepted femininity I should display. Ha ha! I do want to state that I have faced what I call soft-bullying from the Mean Girl personalities.

Love the Claire’s Thunderstorm! Been awhile since I have seen one . Well written !