How Good Can It Get?

On Juno and Aissata’s Love Story, and My Own

Special thanks to Hinge for sponsoring this week’s essay! When I first read Hinge’s No Ordinary Love series, I was eager to be a part of it, so grateful to be partnering with a brand eager to support up-and-coming writers like myself. Hope you enjoy the essay! #HingePartner

In March of this year, I attended the most beautiful wedding I’ll probably ever attend, in Bengaluru, India. Hundreds of guests from the United States flew halfway across the world to celebrate. The multi-hour ceremony took place under fresh flowers and sunshine. The brides’ saris and lehengas dazzled in the sunlight and under the disco ball. Dances were danced, drinks were drunk, heartfelt speeches were shared, and turmeric rice was showered on the happy couple, blessing their marriage.

The nuptials spanned multiple days and were as colorful and lively as anyone could have hoped for. As vows were exchanged, it occurred to me that the bride and groom couldn’t have been better suited - not despite their differences, but because of them. During their vows, the couple joked about their contrasts: his preppiness vs. her earthiness, his love for meat vs. her vegetarianism, the way their friend groups appeared like oil and water on the surface. But it all made sense; they were two interlocking puzzle pieces that fit just right. As we twirled across the dance floor and observed the pujas, the guests and my boyfriend and I kept remarking on the same thing: Can you believe they met on Hinge?

It’s not like we haven’t met happy couples who have met online before. It was just such a stark juxtaposition; centuries-old customs springing from a modern meetcute. But love is still love all the way down; in modern times, we simply have modern ways of getting there. And, besides, no love story is completely traditional - completely linear - to begin with. Take Juno and Aissata, for example.

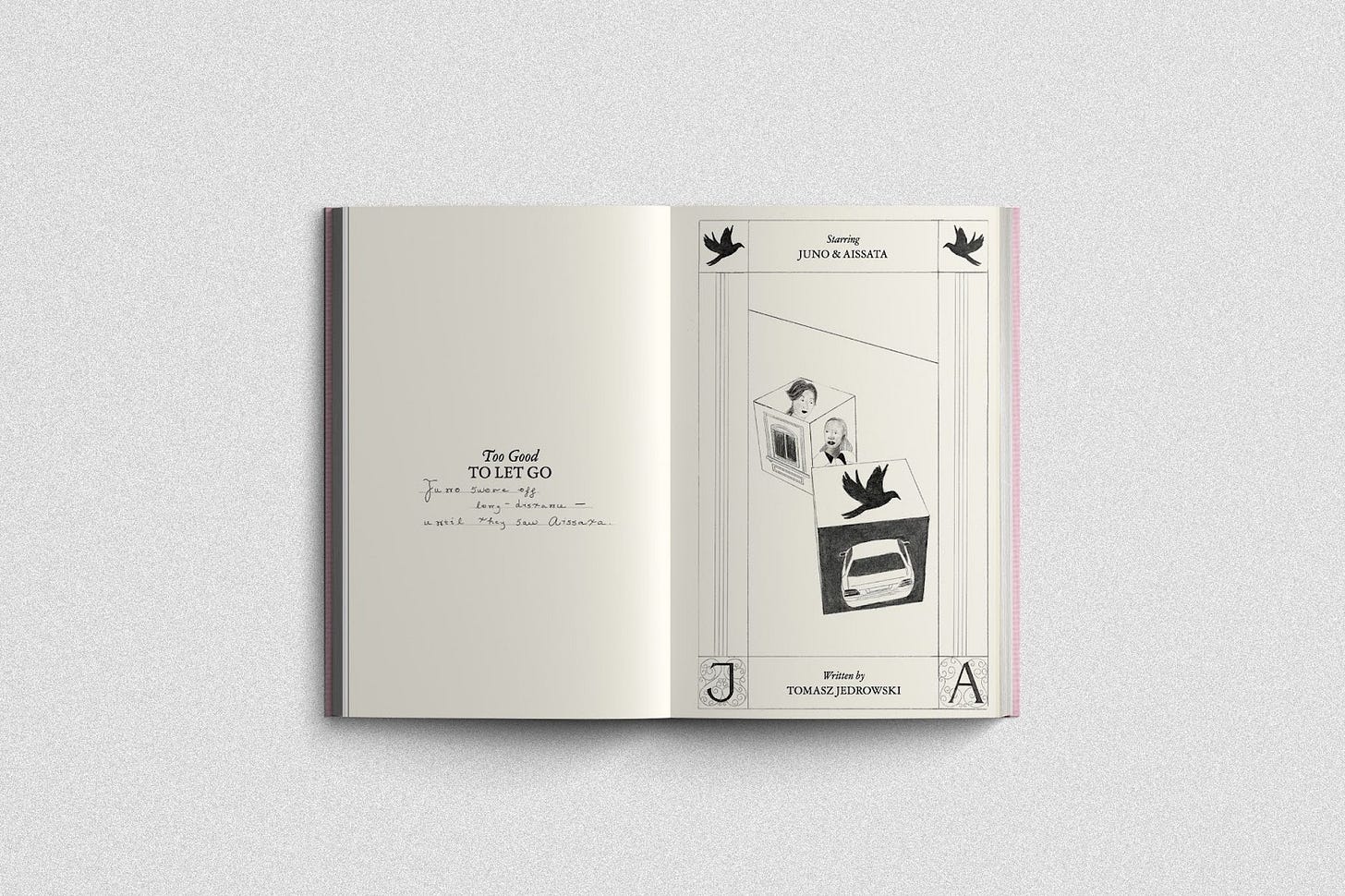

For Hinge’s recent No Ordinary Love essay series on Substack, renowned author Tomasz Jedrowski wrote “Too Good to Let Go,” a beautiful retelling of Juno and Aissata’s love story, which began on Hinge. One brisk December evening, fate had it that Juno and Aissata would send one another a Like on the app. However, months would pass before either one would make a move, Juno nervous and fatigued from countless late shifts, and Aissata reluctant to reach out after sending the initial Like. But within this inaction, numerous micro-actions took place: minutes spent sifting through the other person’s photos, drives home from work spent pondering the other person’s intentions. So much can be said within silence.

The initial move and retreat, the inaction and micro-actions, the time spent staring at the ceiling - it all reminds me of my own relationship. Though my love story didn’t start online, it contains a similar structure to Juno and Aissata’s, beginning with the mixed signals. My now-boyfriend first asked me to hang out in the spring of our junior year of high school, and in response, I always had some kind of excuse. I had dance rehearsal, a family engagement I had forgotten about, a birthday party to attend, and so on.

I can’t pinpoint why exactly I couldn’t commit to a hang - we were constantly texting and talking in class, and socializing in groups outside of school. I enjoyed talking to him, but there was just something in my gut telling me that now was not the time - retreat, retreat, retreat. But, being young, immature, and fearful of confrontation, I couldn’t muster up the courage to outright say No. When asked for a reason, I would draw a blank. I just couldn’t.

Luckily, he made it easy for me. As spring bled into summer, with only a few days left of junior year, I rejected him once more and received a polite but upsetting message in return. I’m starting to get the hint, I will give you some space. No worries. My heart and brain twisted with discomfort. In avoiding being the bearer of bad news, I had the bad news delivered to my door: my admirer had taken the hint. I no longer needed to carry the burden of being confused and pursued.

The following summer was a blissful blur. I spent time with my sisters and friends, unencumbered by the pressure of someone liking me. As September inched closer, my classmates and I received our class schedules for the first semester of senior year, posting them on social media to compare. I mindlessly scrolled through the schedules, my heart dropping when I got to his: we had calculus together, a first- and second-period block class. I wondered what it would be like when we saw each other. Would he be mad at me? Should I avoid making eye contact? Should I go out of my way to be nice?

Just as he had with his rejection, he made it easy for me. On the first day, after chatting with our respective friends, he offered a small smile - a white flag - and asked me how my summer was. It’s refreshing to know how easy it can be to break ice, so easy that it makes you wonder if there was even ice there to begin with.

In “To Good To Let Go,” it took five months for Aissata to reach out to Juno after sending that initial Like. It didn’t make sense for Aissata to begin seeing someone; they were making plans to move cities and start over somewhere else, but their fingers moved on their own, typing out a message asking to meet up.

In my own story, the timing was also slightly off. Senior year is for closure, the period at the end of a long-winded, run-on sentence. Old things must end so new things can begin; otherwise, you’ll find yourself caught in a cycle - never ending, never beginning, forever staying in place.

The first half of our ninety-minute calculus class was lecture-based, involving our teacher explaining a new concept on the whiteboard. The second half of the class involved us practicing the new concept in the form of an assignment; any part of the assignment we didn’t finish became our homework. Our teacher allowed students to move seats to work on the assignment with anyone we wanted, believing that we would learn best working with those we got along with.

Naturally, my best friend and I always sat together to work on the assignment. But, unfortunately, neither of us was particularly skilled at calculus. One day, after spinning our wheels for half an hour too long, we scanned the class for the most capable students, specifically those we were already acquainted with. My friend’s eyes came across a table of boys we vaguely knew, all of whom seemed like they knew what they were doing. Before I knew it, I was being dragged by my hand across the classroom. My former admirer - my future partner - was, of course, among the group of smart students.

Every day, we pushed our tables together and worked through the assignment as a group. Whenever I had a question or asked someone to check my work, my remarks were always, subconsciously, directed towards the boy who asked me to hang out last spring. It was thoughtless on my part - my questions were asked into the ether of our group, and he was the one most eager to answer them.

Over time, his and my chairs started inching further away from the other students without us noticing. We began, unconsciously, working as more of a pair than a part of the group. We found ourselves in constant laughter, and I don’t know why - everything he did suddenly became so funny to me. He would explain his process of working through a calculus problem to me, and I would burst out laughing; I would scoot my chair in a weird way, and he would erupt in laughter too. The rest of the group shot us looks, asking what could be so funny. When we answered with “nothing,” we genuinely meant it. The laughter was born spontaneously; we had no idea where it came from.

When we had more calculus to work on as homework outside of school, our study group would meet up at a coffee shop or a library. The two of us joined the group and were often the last ones there, usually chatting about something other than calculus, filling up the peaceful coffee shop with roars of laughter. Some days, other people in the group couldn’t make it, and it would just be the two of us. And then it was always just the two of us. We would stay at the coffee shop until closing, after which he began inviting me to dinner. And I began saying yes.

When I think back on the relationship’s origins, I’m struck by how easy it all was. When he asked me to hang out the previous spring, his invitations were always laced with the unsettling pressure of a “date.” But senior year, we were just two people working on calculus together, and then two people getting dinner together, and then two people FaceTiming for hours on end, only ending the call when one person fell asleep. Jedrowski writes about a similar easiness between Juno and Aissata:

“It was a lot, but Juno liked what they saw: the overflowing bookcase, the collages on the wall, the little prayer rug, the pink lights. Already it felt like the inside of Aissata’s mind, already it felt good to be in it.”

We officially became a couple at the start of the second semester, to the surprise of no one, especially my best friend in calculus. But senior year needed to end - a period needed to be placed on this sentence. And we did not have plans to go to the same college, or even colleges in the same state. Like Juno and Aissata, we were starting something exactly when we should have been winding things down; it was frustrating and illogical. I didn’t know what to do. But he suggested we take it one day at a time, insisted there didn’t need to be an expiration date. Aissata told Juno something similar; they weren’t planning on moving away forever, just the summer, maybe a little longer. After that, they could figure something out - together.

Nine out of ten times, when people ask for advice, they already know what they want to do; they’re just looking for the courage to do it. When faced with a fork in the road, most of us know which path feels most natural and which feels like swimming upstream. Doing what feels right isn’t always easy, at least at first. Things are going to end and begin whether we want them to or not. What we decide to hold on to and let go of, that’s all that’s in our control.

“The stars looked like they were glued into place, but Juno knew they were moving all the time, forever rearranging themselves,” writes Jedrowski. “Maybe we can’t know how things will turn out, they suddenly thought. Maybe this is too good to let go.”

All that I had was a sensation in my stomach, in my heart - an urging to hold on just a little longer. What’s four years compared to a lifetime? How good can it get?

Since then, nearly seven years have passed. Trips around the world have been made. Apartments have been decorated and dismantled. Bread has been broken with friends and family. Coffee cups have been used and stained, and broken. Tears have been shed, but there’s been far more laughter. How good can it get? I had no idea.

Hey I’m one half of that contrasting, interlocking puzzle piece couple! 🥹

absolutely loved this