Heavy on the Vibes

The Refreshing Nature of a Plot-Driven Story

At long last, this sticky, sweltering East Coast summer is finding its chill - the air is lighter, the heat is less abrasive, and I can step outside in shorts and a sweater (at least before 11 AM, if I push it). The book that’s been accompanying me along this changing of the guard is Liz Moore’s The God of the Woods. Set in 1975 at a summer camp in the Adirondack Mountains, the novel follows the disappearance of 13-year-old Barbara Van Laar, whose affluent family owns the land preserve on which the camp resides.

The novel has been a delightful late summer read - a page-turning mystery with a cast of multi-faceted characters and an eerie woods as its backdrop. It’s a well-written and widely regarded book - it found its way onto Obama’s 2024 Summer Reading list - yet, there’s something childlike about it, in the best way possible. The book opens with a sketched map of Camp Emerson, the Van Laar Preserve, and the surrounding natural environment, aiding with the world-building and harkening to the summer reads and mysteries of my youth. The novel follows characters of various ages - from young campers and counselors to Barbara’s quite dull and highly medicated middle-aged mother Alice. A good deal of the story is told by Barbara’s bunkmate Tracy Jewell, placing readers into the consciousness of a preteen girl for a decent portion of the journey.

Above all of that, what makes The God of the Woods feel particularly nostalgic is its plot-driven nature. The story opens with a crisis - Barbara’s disappearance - and spends the rest of its time putting the pieces together, jumping timelines to construct a series of rising actions that build over several decades. It’s clear that the book is building toward some inevitable climax - the “whodunnit” reveal, the answer to where Barbara disappeared and in what state she will return. After the climax hits, there is a satisfying denouement, leading to a complete ending. The writing remains quite sharp throughout the book, briskly moving the plot forward with the constant changing of perspectives, dropping back in time to peel back an added layer of helpful context here and there. Readers are often left with a pleasing cliffhanger before the POV shifts, allowing the book to read like an elevated Nancy Drew edition.

Throughout my reading experience, I found myself rather amused with how amused I was. Aside from the gripping storyline and clean writing, why was I having such a great time? When reflecting on some of my favorite fiction reads of the last year or two - which among The God of the Woods, include The Rachel Incident by Caroline O’Donoghue and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin - I’ve gathered that the throughline appears to be their plot-forward qualities. “Plot-forward” may seem redundant when discussing works of fiction - isn’t plot a requisite? Don’t all novels need a series of events to unfold - for there to be some kind of development over time for the reader to stay invested? Certainly.

However, in many recent works of contemporary fiction, the plot almost acts as set dressing so character can take precedence. Within popular novels like Normal People by Sally Rooney and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh - and more niche internet reads like Alexandra Tanner’s Worry and Sheena Patel’s I’m a Fan - and, to a certain extent, even Miranda July’s novels, the book’s protagonists undergo a journey that is largely internal. In contrast with the aerial view perspective that The God of the Woods takes - reinforced by the sketched map of the setting at the beginning - the reader lives within the minds of one main personality in these character-driven books.

This is a distinction from a story simply being told in “first person” or “third person” language. Swapping in different pronouns doesn’t cause the discrepancy, it’s the content of the story itself that does. Rather than witness a quest unfold across time and space from afar, readers traverse the complex inner world of an eccentric protagonist as they move through life or sit still. Thoughts and feelings are prioritized over the more typical and linear kinds of “actions” one performs in a book, making the genre feel more inherently feminine. As such, it’s a micro-genre that’s revered by young women and book lovers on TikTok (otherwise known as “BookTok”) and that’s being dubbed “no plot, just vibes,” for its seemingly slower pace, more self-centered conflicts, and non-traditional plot structure.

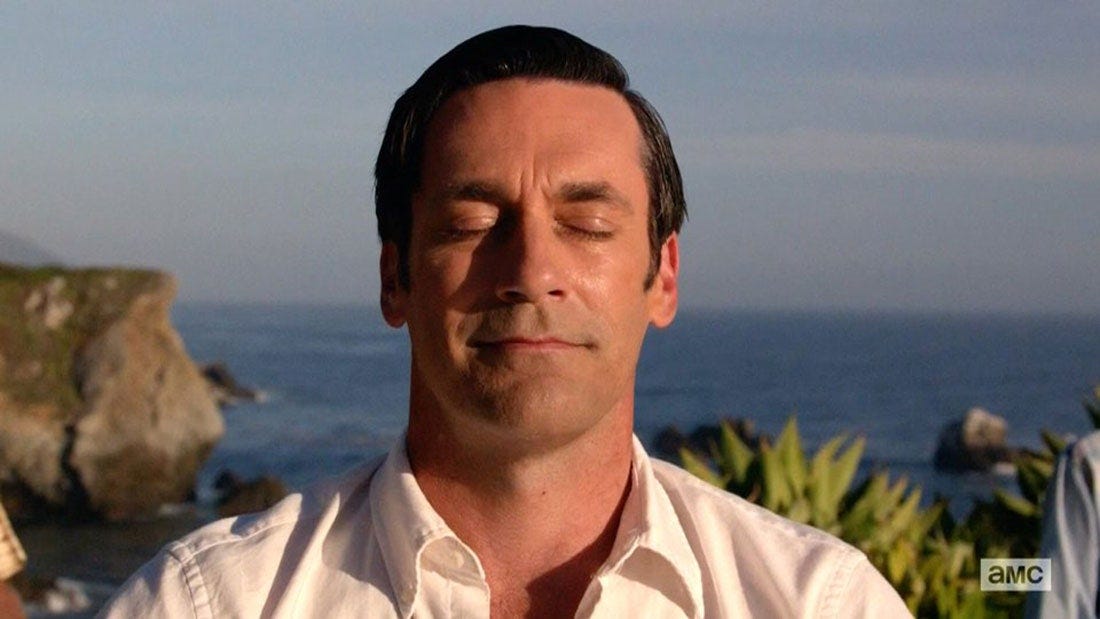

I’ve often been drawn to these types of character-driven stories - across all mediums. One of my favorite television shows of all time is Mad Men, which is arguably a quite character-driven show. Across its seven seasons, not much actually “happens" - there are several company acquisitions, a few deaths, women rotating in and out of protagonist Don Draper’s life like a revolving door, and Draper dropping Lucky Strike cigarettes as an advertising client for ethical reasons. In the series finale, Draper appears to be cleaning up his life - he escapes the hardened corporate world of Madison Avenue for the breezy openness of 1970s California. He makes amends with all the women in his life, confesses his lies to them, and signs himself up for an oceanside spiritual retreat. In the show’s final shot, Draper is meditating on the California coast and a smile creeps across his face - the show then cuts to the iconic 1971 “Buy the World a Coke” ad for Coca-Cola. Draper’s journey was a full circle - he learned to forgive himself and allowed the world to forgive him, forayed into the ideologies of universal love and acceptance, and co-opted those sentiments for corporate gain. He is ultimately in the same role he was when he started, only changed subtly by the intense inner journey he undertook.

Novelist Coco Mellors tells Elle that her strategy for developing compelling plots is “characters x time = change.” “If characters are stagnating or not changing, it ultimately won’t make for exciting or dramatic storytelling,” she says. That is where the nuance in character-driven stories lies. For the story to be interesting, it needs to involve some arc, even if that arc is a subtle slope and ultimately lands the protagonist in a similar place as where they started. Some kind of shift still needs to occur. My issue with many contemporary character-driven novels is that the arc is often so subtle that it’s almost flat. And the protagonist herself isn’t often beginning in the most interesting or exciting state of being to begin with, at least in my eyes.

Writer Caelan McMichael spells out this type of contemporary fiction protagonist, illustrating “a girl in her twenties bask[ing] in an apartment in New York City and ruminat[ing] on heterosexual love, further intensifying her sense of ennui.” Her biggest personal dilemmas include harrowing existential thoughts, declining mental health, heavy alcohol and drug use, and the sense that her youth and beauty are fading by the minute. She is an unhappy and numb girl, succumbing to the vices of her time, developing a soft addiction to pills or men or Instagram stalking. She wants to do something meaningful with her life if she could just get out of bed. Swap out a few details - perhaps the city, perhaps the age, perhaps the vice - and you have the protagonist from a number of the aforementioned novels, including My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Normal People, Worry, and I’m a Fan.

It’s worth noting that I do think a compelling story can be told with this kind of protagonist - and it should be told. And it doesn’t, by any means, always have to involve her ending the novel with her life completely together, on a straight and narrow path - that would be much too predictable, and for many, much too fictional. This type of sad, indifferent girl protagonist is relatable to many modern young people, who feel overwhelmed by modern social- and climate-related ills and compelled to dull their anguish with scrolling. Seeing this type of personality - and its variations - illustrated in modern literature is validating in a sense, and perhaps melts some of the feelings of isolation associated with teenagehood and young adulthood.

Nonetheless, the typical contemporary character-driven story and its typical, tragic, detached protagonist are becoming a bit boring for me. So too are the hordes of fans romanticizing this typical distant, sleepy personality, who dwells kitty-corner to the coquette and the femcel, two other personalities and aesthetics that I’ve grown dizzy from even mentioning, let alone interacting with online and in fiction. I’m not necessarily looking for a rock-solid woman to lead a story, but I’m growing tired of reading about the same disaffected one, who is resistant to any kind of uplifting change, again and again. Similar to how her looming potential and the overarching societal conditions of her time weigh heavily, her fictional hopelessness weighs on me too. I too have developed a sense of ennui - and I need a compelling plot - or at least a more compelling inner world - to invigorate me.

Sally Rooney’s new book Intermezzo comes out September 24 - early reviews are calling it “her most ambitious book yet.” Writer and Limousine podcast host Leah Abrams calls it “another Rooney book where quiet, nobly suffering women are cured by magical dick.” The jury’s out on if I’ll tap in, but I think you can probably guess the answer. If you know of any books that open with a map, feel free to send them my way.

Yeah, the pitfall of this genre is that it all just becomes an exercise in narcissism with the same narrow class of people (with superficial diversity) getting indulged to feel as though their mundane lives are more book-worthy and aspirational than others.

I do think "I'm A Fan" is a notable exception though because the protagonist is so genuinely cringeworthy (in the best sense possible) that the novel seems like it's about more than the author's desire to be seen through a carefully crafted image via her avatar protagonist. Because who'd ever want to be seen as that protagonist in that book?

Great piece. I think what makes plot-driven books so exciting is that the stakes are just higher, and that leads to more emotional investment in the story. Without those high stakes these plot-less novels rely on either relatability (Normal People) or cringe factor (like in I’m a Fan or MYORAR).