Everywhere But Nowhere

Brandy Melville, Parasocial Marketing, & Brands Acting Like People

When I was twelve, I never considered who the CEO of Brandy Melville was because why exactly would that matter? The brand had an ethos that eclipsed whatever individual was at its helm. During the 2010s, the CEO of Brandy Melville was Instagram. Was the grids of tanned, blonde, small-bodied girls who occupied the company’s product photos and store floors. In 2012, if you would have asked me to guess who ran Brandy Melville, I’d probably pause and stare at the floor - I wouldn’t know and I wouldn’t care. When I was twelve, Brandy Melville was one of the more important fixtures of teenage It Girl-dom, and it was that way because of the teenage girls in my school and in my phone. Not because of some guy or some group of guys.

Fast forward to 2024 and the release of HBO’s Brandy Hellville & The Cult of Fast Fashion and, shocker, it turns out some guy was at the helm all along. An antisemitic pervert, no less. Specifically, a guy named Stephan Marsan, who famously peered down at teenage customers from a crow’s nest within Brandy’s Soho location. Concealed within the flagship store’s office, Marsan would press a button that would signal the teenage employees to recruit fellow teenage shoppers who have the “right look” to work at the company, never mind their resume. The documentary revealed many bone-chilling details about the company’s inner workings, many of which you probably could have guessed given the fact that it’s a clothing brand for young women that only produces clothing in one, pre-pubescent size. Full-body pictures of prospective employees were required to be sent to Marsan, including alleged photos of chests and feet specifically. Employees of color were exiled to the out-of-sight stockroom, while white girls worked the floor. A group chat, spearheaded by Marsan, disseminated antisemitic memes. A 21-year-old staffer staying in a “company apartment” reported sexual assault. A whole lot of mess, a whole lot of filth.

Overall, Brandy Hellville was a mediocre documentary in form. The film’s contents were spread too thin by trying to touch evenly on each of the brand’s shortcomings - the parts about the impacts of fast fashion, for instance, felt a bit tangential to the unique evils of Brandy Melville, specifically. In my eyes, the most illuminating parts of the film centered on the secret sauce of Brandy Melville: its marketing efforts. Or non-efforts, as I’d call them.

Throughout my teenage years, Brandy Melville’s essence was omnipresent on social media - particularly on Instagram and Tumblr. There was a very specific type of breezy, coastal All-American feminine aesthetic that became ubiquitous with the brand name. Denim shorts in front of white brick walls, floral baby tees, striped shirts with combat boots, daisy chains in straw blonde hair - all was typical of a “Brandy Girl” look. This sort of easy, cool, forever summer, California girl absorbed into the fabric of my then-supple aesthetic preferences, coloring my developing sense of taste like hot pink dye.

Despite Brandy Melville’s omnipresence, the brand had virtually no corporate qualities, at least in terms of appearance. Brandy Melville had zero billboards. No TV commercials, no magazine spreads. No event sponsorships. No traditional, splashy branding pushes. Like Lana del Rey, American Apparel, and many other cultural facets that grew in popularity via the internet, when I looked up from my phone, it was as if I had dreamt the whole thing up. Of course, what I didn’t realize at the time, was that Brandy Melville was an early adopter of influencer marketing, what would later become a major marketing channel for DTC companies. Until I realized that, it felt as though my peers and I were pioneering a brave new aesthetic. We replicated and disseminated what we believed a Brandy Girl to be like on social media, supplementing Brandy Melville’s paid influencer efforts with earned media of our own making. We were influencers in our own right, blind to the marionette strings yanking on our elbows and knees.

Brandy Melville has remained successful because of its quiet, easy ubiquity. There is no sense of urgency from Brandy - no clearance section, no rewards system. Their website lacks a home page - just iPhone photos of clothes and their prices, emulating Depop listings. Everything about their brand presence is nonchalant - even in the wake of a scandal. After finishing Brandy Hellville, I instinctively unlocked my phone, clicked on the Instagram app, and typed “Brandy Melville” in the search bar. It’s business as usual on there - photos of young pale Brandy Girls eating vanilla ice cream and drinking matcha, with some occasional, confusing videos of girls singing and playing the guitar. The comments on the posts are limited and each one has the same eerie caption: #brandyusa.

It all feels a bit uncanny - nonhuman. I imagine each post receiving a “#brandyusa” stamp with a robotic arm at the end of a conveyor belt in a factory somewhere, tucked neatly inside a dark black box. But then again, what was I expecting? A notes app apology? This brand gained popularity like carbon monoxide, filling the air with its noxiousness, but emitting no color or odor. Why would I expect them to respond to Brandy Hellville in any fashion other than silence?

In contrast with Brandy Melville, many other brands these days seek a social media presence that’s akin to an influencer’s, attempting to mine a relationship with potential customers that’s as noisy as it is parasocial. It’s not uncommon to see companies tweeting at each other like real people - McDonald’s and Wendy’s beefing one another on Twitter, Letterboxd gassing up movie stars in their Instagram comments, the list goes on. Similar to Brandy Melville, these brands are attempting a version of nonchalance, but it’s a kind of disregard for traditional corporate poise. We’re not a regular corporation, we’re a cool corporation, they insinuate via their casual online presence - typing in all lowercase, perhaps even attempting meta-strategy by referring to the “intern” behind the curtain, or the boss that’s making them type these “cringe” tweets. There’s a kind of overt self-awareness that horseshoes back into calculated strategy - the consumer becomes so aware of how self-aware the company is that it becomes clear that it’s a deliberate communication tactic, and is thus rendered awkward.

Most recently, no company’s attempts at parasocial marketing have been as aggressive (or successful) as Duolingo’s. Over the past three years or so, the language-learning app has developed an immense presence on TikTok, posting humorous videos that star “Duo,” the green owl that acts as the Duolingo mascot. The strategy was the brainchild of then-23-year-old Social Media Manager Zaria Parvez, who simply asked if she could start making videos on the brand’s dormant TikTok account in 2021, according to an interview with Contagious. Armed with an iPhone, a green owl suit, and an understanding of how people talk online, Parvez began by leaving cheeky comments on others’ TikToks, before eventually making sketch-style videos on the company’s page, enabling the account to accumulate 12.7 million followers in three years. The character Duo has conducted seances, twerked on office desks, proposed to Dua Lipa, and developed a sassy personality built off jokingly bullying people into not skipping a language-learning session on the app. Duo has developed a life for himself that extends beyond the Duolingo app itself - Parvez says that the owl was asked to be a featured creator at VidCon in 2022 instead of being included on a typical brand panel. The line between corporate personality and personality personality has blurred.

This era of parasocial brand identity - of brands becoming more like people - is a natural development of brands becoming more closely intertwined with our emotions and senses of identity. It’s a development that Mark Wieczorek traces for Front Row - theorizing that the First Era of Brand occurred when customers were given the opportunity to select what brand of goods they wanted at the grocery store. Before 1927, it was typical for a grocer to shop on the customer’s behalf. This all changed when Tot’em Stores (renamed 7-Eleven in 1946) allowed customers the opportunity to handle products themselves. This kickstarted the overwhelming illusion of mass-market choice in grocery stores, as well as brand preferences. Individuals and their families would become attached to specific brands for certain items. You’re either a Colgate or Crest family. The sight of the pancake mix brand your mom always purchased for weekend breakfasts evokes warmth. I’ll probably buy the same brand of laundry detergent my family uses forever, simply because of their loyalty to it. These and other fuzzy associations abound.

Wieczorek argues that the Second Era of Brand began at the turn of the millennium, when many brands gained enhanced access to customer data and learned how to communicate with shoppers more directly, specifically through social media. “Performance marketing” - a form of marketing that prioritizes measuring specific actions, like purchases driven by ads - was born. Today, Wieczorek argues that we’re entering a Third Era that’s primarily concerned with authenticity - a kind of natural next step for companies that are already peering into customers’ lives via their data. By using the behavioral information they have at their fingertips - delivered via third-party providers and chronically online fresh college grads - companies are seizing the opportunity to meet customers where they’re at, developing identities like Duo’s that are evocative, but grounded in how people actually communicate on digital platforms.

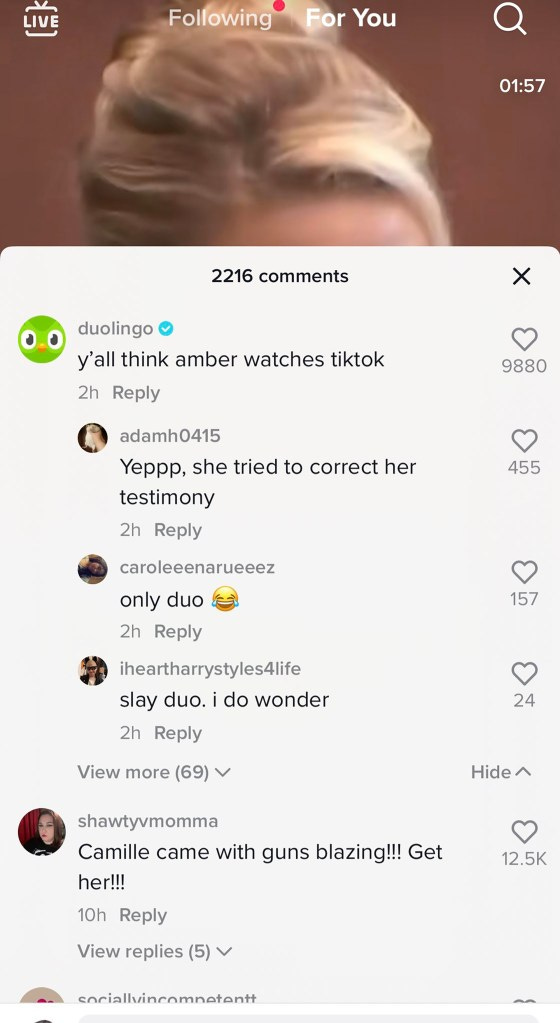

Brands beefing with one another on Twitter, becoming personalities in their own right, making jokes that dance on the lines of appropriateness - it’s all quite funny, of course. It becomes a bit less funny when you remember the bottom line that’s still being prioritized and the personal data they’re leveraging to target and tailor many of these messages. Becoming overly inundated with these brand interactions becomes exhausting - the contrived nature eventually rises to the surface like smoke from a fire. During the Depp v. Heard defamation trial in 2022, the Duolingo TikTok account commented on a trial clip of Amber Heard explaining Johnny Depp’s abuse towards her throughout their relationship. “y’all think amber watches tiktok,” the company dumbly weighed in. Thinking about marketing associates - heads clustered together over Zoom - brainstorming how to drive clicks off an abuse victim’s testimony makes my stomach churn.

The parts of Brandy Helville that I sadly identified with most were the anecdotes told by former Brandy employees and shoppers. Reflecting on the desires of their tween and teenage years, the young women expressed how gratifying it was to receive validation from Brandy Melville - whether it was an Instagram repost, a job offer, or an opportunity to do unpaid “research and development” work. There’s still a twinkle in their eyes when reflecting on seeing the iconic white brick wall - the backdrop of many Brandy photoshoots - for the first time. My boyfriend glanced down at me oddly from the other end of the couch, commenting on the twinkle in my own eye as I reacted to these girls’ reactions with the same warped fondness.

“[You] need to trust that the person on the other side of the phone will close the loop for you,” Parvez says of her marketing work at Duolingo. As brands attempt to act more like people, their success will rely on us treating them more like people - like the revered content creators that they are. Entertainers with crafts for us to boast and share. But companies are, of course, not people. And they’re not always entities that have our best interests in mind - particularly companies like Brandy Melville, which rely on attention, insecurity, and opacity to move product. In a digital climate that’s allowing brands to become more personally invasive - I feel more compelled to purchase from businesses that don’t attempt to act like popular girls or class clowns. It’s less exhausting to be entertained when you’re not also being sold to, which is why the noisiness of marketing from brands like Duolingo is likely unsustainable in the long run.

Brandy Melville, on the other hand, has sadly survived the decade by finding the right balance of para-sociability. Both the source and the antidote to pubescent insecurity - Brandy Melville still feels far from contrived because it draws from real desires. Desires to be smaller, blonder, and better. As brands become more intertwined with entertainment and ads become more intertwined with day-to-day life - in and out of the home, on and off of our personal devices - we’d do good to keep our noses in the air. Just because we can’t see the smoke, doesn’t mean it’s not there.

In all honesty we should educate young people ie. young consumers to be more mindful when shopping, when living, but also when talking about fashion with the so-called adults, hopefully in the longer term someone like Brandy leaves our planet because truly educated young consumers didn't find them so dandy. Thanks for giving me and others food for thoughts. 🤓📚🔖💯

This one hit home for me working in brand social media. Particularly, the shortcomings of a personified brand presence. In real-time, I’ve seen that shift from brands using “I” to reverting back to using “we” while still trying to remain relevant/relatable to the customer. There are only so many ways you can humanize your brand until it’s all been done.