Several days before moving to New York City two years ago, I embarked on the dreaded, but necessary journey all individuals downsizing and/or moving cross-country must embark on: sorting through my colossal accumulation of stuff. It was a collection that spanned about twenty-one years, mostly all housed in a bedroom I dwelled in for the same amount of time. Having never lived outside of western Washington, let alone in another time zone, rummaging through the things in this room was highly emotional. I was catapulted back home for an unforeseen and unsteady two years in 2020 and hadn’t bothered to update my bedroom’s decor much from when I was a teenager. The same pink paint I selected at age seven adorned the walls, now faded to a muted mauve-grey. The same Audrey Hepburn, pop-art graphic hung above my bed, once a teenage girl’s muse, now a reminder of a fading youthful naivety. My prom dress and college graduation gown hung side-by-side, each stained with respective sweat marks. The bedroom had the aura of an abandoned carnival fairground - bright colors and sugar sweetness gone dull and tasteless with time.

I was a puddle on the carpeted bedroom floor, knees pulled into my chest. We were running short on time now - I was just a few days away from moving - so my mom and sisters held up items of clothing one by one and asked whether they should be kept or donated. Paralyzed by stress, I gave a nod at the ones to keep and a head shake at the ones to donate. I abandoned all sense of taste and discernment in this erratic state - what I decided to keep and what I decided to donate was all based on pure impulse. On the fact that I had a finite amount of cardboard boxes and was told by my mom that I couldn’t use my childhood bedroom as a storage unit, at least not for Brandy Melville cardigans from middle school. Some stuff needed to go.

When the cardboard boxes finally arrived in Manhattan, a few weeks later, you can imagine my amusement upon discovering what filled a decent fraction of the containers: random commemorative t-shirts, crewnecks, and hoodies from community events, concerts, and local happenings, collected over many years. A decade-old dry fit shirt obtained upon completion of a 5K walk/run for colon cancer awareness. A complimentary shirt distributed to all University of Washington students at select Seattle Mariners games. Merchandise from an off-broadway production of Hamilton. Freshman orientation swag. Harry Styles merch that had gone through the wash twelve too many times, the graphic peeling from the fabric. And most notably, every single t-shirt or sweatshirt I had received from participating in any kind of organized extracurricular activity, including a bright-red quarter zip with my name stamped on the chest from the year I danced the Sugar Plum Fairy in my dance studio’s production of The Nutcracker, as well as a God-awful purple and yellow long-sleeve gifted by the magazine I wrote for in college.

It goes without saying that the majority of these t-shirts and sweatshirts are quite tacky. They won’t ever find their way into my daily wardrobe. And yet, I hang onto them. I had to purchase a separate Ikea nightstand just to contain them, and it can barely close shut. I have several plastic acrylic containers from Target under my bed filled to the brim with them, and could probably fill up several more. I collect these items under the guise of using them as “sleep shirts” or “workout clothes” as if I won’t just rotate the same two or three tops for sleeping and exercising, as I’ve done for years. I’ve conducted several closet cleanouts since moving to New York, and have given away many items that I’ve purchased and failed to wear within the same calendar year. The T-shirts and sweatshirts don’t budge.

I’ve never considered myself a person who is particularly sentimental about physical items - just a bit lazy. When I lived in Washington, I would let birthday cards pile on my bookshelf until dust collected, dollar bills still tucked into their creases. Trinkets and clothes from my childhood were strewn across my bedroom, garage, and hallway closets. It was always possible to find a nook or cranny to store something, like a squirrel with its acorns. There was no need to be discerning, the whole house was my oyster. That may have worked when I was a child and had a smaller accumulation of things. However, I’m now a grown woman with twenty-three years worth of life souvenirs - there’s now a need to be discerning. And I’m having trouble with it.

Minimalism is not intuitive to most modern dwellers. Particularly if they grew up in a house or tight-knit community, in which physical items could fill up more space, could endure for much longer than they can in an apartment, or temporary living space. My extended family has lived in the upper left corner of the United States for decades now, and it shows in some of their living habits. Growing up, my family garage was always rife with stuff. I used to hear stories of relatives with hoarding habits, holding onto items far past their point of expiration - books with the pages falling out, movie ticket stubs, and ketchup packets. The modern-young-adult-urban worker often swings to the other extreme - in which all is ephemeral, all is without roots. Jumping between cities and between people without commitment, washing your hands clean of history, always turning to a fresh page, perhaps out of economic necessity and perhaps for emotional ease. Optimized, sanitized, and without friction - this is the ideal that’s been touted via lifestyle influencers. Between friends and Hinge matches.

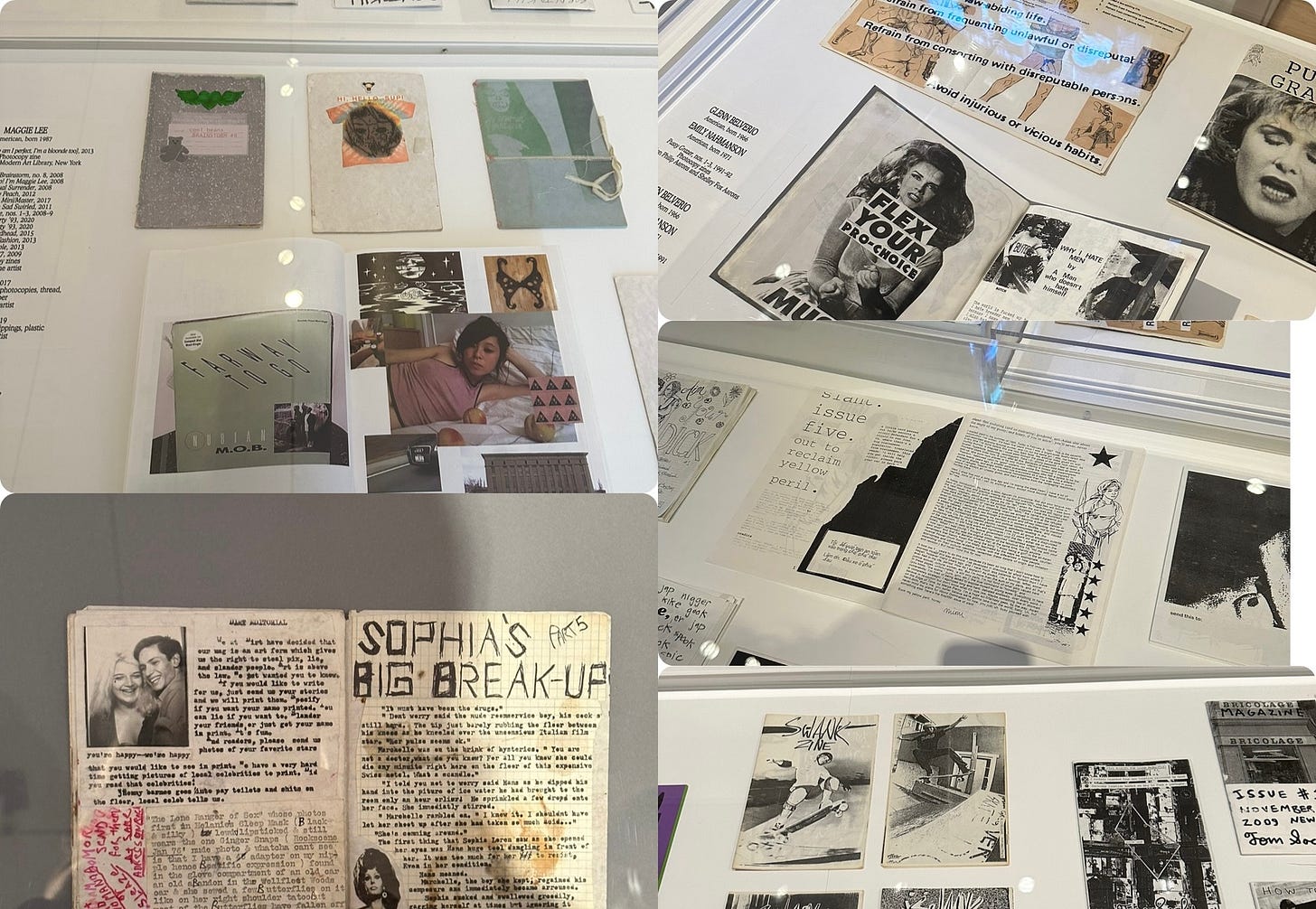

Last March, I went to the Brooklyn Museum to see the Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines exhibit. The exhibition contained “zines,” or self-made magazines of text and images from the 1970s to 2010s, many of which were devoted to various punk, feminist, and queer subcultures. Some zines acted as vehicles for personal confession and self-expression, others operated as conduits for consciousness-raising and organizing, and others combined all these functions, collapsing the Personal and Political in true second-wave feminist fashion. What struck me most about the exhibit was the sheer physicality of the archive - hundreds of booklets that you could leaf through with your actual fingers. Producing and distributing these involved exchanging them between hands or otherwise mailing them, by placing the zine in an envelope, licking it closed, writing an address, and sticking a stamp in the corner with your fingers. There was material evidence of your efforts and reach, of the connections you were establishing through your craft.

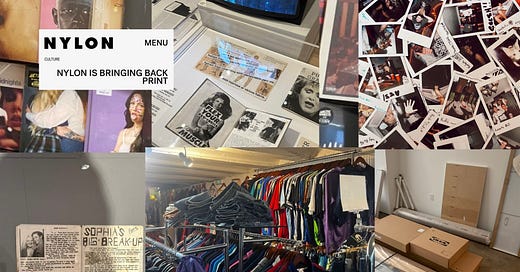

It’s no secret that people online tend to wax nostalgic - and the way they discuss and practice media consumption is no exception. Young people have taken to collecting vinyl records over the past decade. They’ve adopted more physical forms of photography (Polaroids, film, disposables, etc.). And with publications like NYLON going back into print, it’s clear to me that a desire to return to more physical forms of media is on the horizon, particularly coming out of a pandemic where all was forced to be digital.

I certainly share this desire for a more physical existence. That phrase feels counterintuitive - “physical existence.” My existence is necessarily physical, if I ceased to exist, I would also cease to be physical. In some respects. My work, however, would endure digitally. My blog, the drafts in my Google Docs, etc. But its occupation in the digital space makes it feel much more removed. Writing for an online audience of thousands is a lot less daunting when you can’t see the thousands. If my readers were all seated in an auditorium, listening to me read from a microphone on stage, that would make it all feel a bit more real. The fruits of my labor would be a bit more tangible. Instead, writing online can sometimes feel like tossing my words into outer space, waiting for them to catch in someone’s orbit. I sometimes wish I could see readers consuming my work with my own two eyes to feel like I’m actually doing something. Like I am something.

If and when we culturally return to this more physical space in media - and it’ll certainly never be as it was twenty or thirty years ago - we’ll still have to figure out what to do with all of our stuff. With the books, with the Polaroids, with the merchandise. We’ll have to reconcile the fact that physicality and ephemerality are typically at odds with one another. That creating and consuming something that you can hold in your hands means also being discerning about what you decide to create and consume. We only have so much space, we only have so much we can preserve ourselves. Perhaps such discernment would be a salve for many young people, whose eyes are often bigger than their appetite. Who have often been conditioned to favor quantity over quality, speed in consumption over patience, and having instant gratification at their fingertips.

As for me, until I learn such discernment, I’ll continue to lug my commemorative T-shirts from apartment to apartment, from city to city, attempting to allow large pieces of my past to endure. Physical reminders that I’ve existed and lived a multi-faceted life. Identity tokens. I can recall slinging this sweatshirt over my shoulders as I warmed up at the ballet barre in high school. I remember crying in that threadbare crewneck that used to belong to my grandfather about something I now can’t recall. The good, the bad, and the boring, I’ll hang onto it all the best I can.

Such a great one ! What is it with those tshirts ?

Amazing insight in the nostalgic mind of one of us :)